Donal Lunny (RollingNews.ie)

Donal Lunny (RollingNews.ie)On the 50th anniversary of the release of the album Planxty MAL ROGERS considers its significance

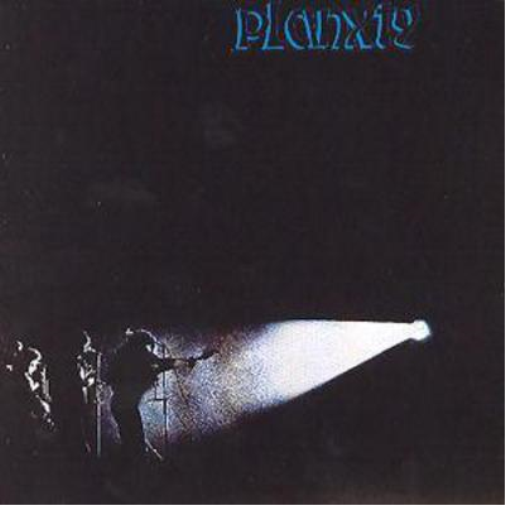

IT IS a valid question. Was the album Planxty, recorded in London during 1972 and released in 1973, the best folk record of all time? Not just the best Irish folk record, but arguably the most seminal, the most influential, the most significant folk record in the history of recorded music.

It is a bold claim; some might even say an overblown one. But there are valid reasons for describing it as such.

The main plank of this theory is that this album, more than any other, was key in taking a simple folk music — and at that time still a moderately obscure, niche interest — to a huge global audience. Very few, if any, other albums ever managed that extraordinary feat.

Not only was a massive international audience created — the album inspired a generation of musicians, singers and dancers around the world to embrace Irish music. Today there are Irish traditional bands made up entirely of Japanese aficionadas, there are uilleann pipers everywhere from the Netherlands to Uruguay, and Irish dancers of every nationality and ethnicity.

Irish music is global phenomenon.

By the early 1970s, when Planxty released their magnum opus, Irish music had certainly become a significant genre. Sean Ó Riada, the Chieftains, The Fureys, The Clancys and The Dubliners had all moved the music away from the danger zone of extinction, and most importantly, had fostered an interest in Irish music among some younger musicians.

In America, in Britain, in most European countries, young musicians had turned to rock music. That was true in Ireland as well. But significant numbers, hearing the ballads of the Dubliners, or the uilleann pipes of Finbar Furey, had in significant numbers, embraced traditional music, folk music, ballad music.

Christy Moore said of The Clancys: “Irish music was banned and denounced, and survived centuries of oppression. But all the Clancys had to do was sing them once and they sprang back to life. Their revival was a turning point in our history and culture. They turned our heads and we began to wonder where we were and who we were and many of us loved what we saw.”

The 20th century was kind to Irish music. The tradition was saved from extinction by the likes of piper Patsy Tuohy and fiddler Michael Colman, whose recordings in America suddenly awakened Irish people to the musical treasure trove they were sitting on.

The two cultural caryatids of rural Ireland and the Diaspora – the showbands and the céilí bands – began to crumble mid-century, and were overlapped by artists from Ó Riada to Ronnie Drew. They gave graphic evidence to a waiting world that Ireland boasted one of the finest stores of ethnic music in the world.

That’s a very condensed history of the tradition, and doubtless open to debate. But the one indisputable fact is that Irish music became a phenomenon of real cultural (and commercial) significance because of the advent of one band – Planxty.

It was Planxty who gave the music an edge, a profile that was jagged and vibrant, and it is no exaggeration to say they provided the soundtrack for life in Ireland fro the 1970s.

Planxty were a seminal band in so many ways — not least because they were the first Irish band who started playing traditional music with a rock attitude. The individual members of Folk’s Fab Four each contributed massively to the tradition.

Liam O’Flynn secured a place for the uilleann pipes in Irish and contemporary, music forever after. His undoubted musicianship and the fact that he was one of the two or three finest uilleann pipers in the world, brought the traditional music fans along.

Andy Irvine and Donal Lunny’s use of the bouzouki and mandolin ushered in a new lease of life for these instruments far beyond their home territories of the Balkans and Naples — many music historians now claim these fretted instruments are more empathetic with Irish music than the guitar, sounding more like the ancient metal strung harps of antiquity.

Christy Moore’s song-collecting managed to resurrect many traditional ballads that are now a standard part of the Irish repertoire. This month he told The Irish Post: “Playing with Planxty, particularly in those early days of 1972/73 was an amazing experience.

Fifty years on I still cherish the music we made, the good times we had along the way. Standing beside Liam Óg Ó Flynn, Andy Irvine and Donal Lunny was an important part of my working life.

“That first Planxty album still resounds, the music still sounding fresh. It has aged better then the lads that made it. Sadly Liam no longer with us.”

Andy Irvine photo by Brian Hartigan

Andy Irvine photo by Brian HartiganInnovation and authenticity

PLANXTY had the imaginative idea of mixing instrumental airs airs with the more commercially appealing chorus style songs of the Clancys and Dubliners, without losing the respect of the traditional purists.

One of the tracks on the album Raggle Taggle Gipsy/Tabhair Dom Do Lamh, started a fashion in Irish music that had rarely been tried before — segueing from a song straight into a traditional piece of music, in this instance a Turlough O’Carolan composition, in English known as Give Me You Hand. A simple enough notion, although never attempted before, but now ubiquitous throughout Irish music. The tricky transition from song to air was apparently Donal Lunny’s contribution, the first of many from a man who has subsequently had a hand in most of the innovative ideas in traditional music since the seventies.

These baroque arrangements of traditional material gleaned from nobody knows where, transformed Irish music and helped bring it to a whole new, worldwide audience.

Planxty’s version of Si Bheag, Si Mhor – the first tune ever written by the great 17th-century harper O’Carolan — somehow took it away from The Chieftains’ almost classical treatment of Turlough O’Carolan’s music into a setting that was unique, imaginative — and incredibly infectious.

Liam O'Flynn with the RTE Orchestra — also pictured to the right Seán Keane (Photocall Ireland)

Liam O'Flynn with the RTE Orchestra — also pictured to the right Seán Keane (Photocall Ireland)The band’s origins were, as so often happens in music, the serendipity of a certain collection of individuals coming together and producing something truly miraculous. The four musicians basically drifted together sometime towards the end of the sixties, and by the next decade were household names.

Musically Planxty were the success story of all time in Irish music, but financially, the band were less successful.

As with most explosively creative collaborations, the band’s history is littered with disagreement and disarray. Record deals went awry, constant touring took its toll.

Unsurprisingly, by the time the third album came round, a split was on the cards. Donal Lunny was the first to go, followed shortly after by Christy Moore. O’Flynn and Irvine kept the band afloat, drafting in various artists, the most successful, from a musical point of view, being Paul Brady. But the ship had been holed below the waterline with the departure of Moore and Lunny, and by 1975 one of the greatest bands folk music has ever seen were no more.

The four original members followed individual careers with predictable success. But the ghost of Planxty haunted them, and in 1978 a reunion was mooted. This had less impact than the band’s genesis, but nonetheless in four years or so they produced another three ground-breaking albums, After The Break, The Woman I Loved So Well and Words And Music.

Planxty once again split and went their separate ways, this time with varying fortunes. By the eighties Christy Moore had become — and remains —one of Ireland’s most respected performers, someone who can pack the Albert Hall armed only with a guitar, a handful of chords and a huge personality. However by the 1990s he had been forced to retire due to ill health, with the years of touring having taken their toll.

Christy’s gradual return to live performance this century opened the way for the third coming. This time the reception was ecstatic.

The four original members of Planxty, plus a handful of others who have passed through the band — Paul Brady, Bill Whelan (Riverdance composer), Shaun Davey and Matt Molloy (Bothy Band, Chieftains) - have continued to dominate Irish music.

Sadly Liam O’Flynn died in 2018 aged 72.

Planxty’s collective genius transformed Irish music forever, and their album, released fifty years ago this year, is arguably the most important creative project mounted in Ireland in the 20th century

Track listings

Raggle Taggle Gypsy/Tabhair Dom Do Lámh

(Traditional; arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)

Arthur McBride (song)

(Traditional; arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)

Planxty Irwin (Turlough O'Carolan)

(Traditional; arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)

Sweet Thames Flow Softly (song)

(Ewan MacColl)

Junior Crehan's Favourite/Corney is Coming (reels)

(Traditional; arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)

The West Coast of Clare (song)

(Andy Irvine)

The Jolly Beggar/The Wise Maid (song/reel) – 4:23

(Traditional; arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)

Only Our Rivers (song) – 4:04

(Mickey MacConnell)

Sí Bheag, Sí Mhór

(Turlough O'Carolan, arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)

Follow Me Up to Carlow (song)

(Traditional; arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)

Merrily Kissed the Quaker (slide)

(Traditional; arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)

The Blacksmith (song) – 4:09

(Traditional; arranged by Moore, O'Flynn, Irvine, Lunny)