EAMONN Andrews was the first in a long line of Irish journalists, entertainers, actors and comedians who were to become a prominent feature of British broadcasting. This conveyor belt of talent that left Ireland for Britain includes a range of personalities from Terry Wogan to Olivia O’Leary, and from Henry Kelly to Graham Norton.

But Eamonn Andrews was the first to carve out a career on the British airwaves — followed closely by another figure who was a mainstay of light entertainment in the middle decades of the 20th century — Val Doonican.

But while Doonican focused on crooning and a spot of blarney with a Delaney’s Donkey here and a Paddy McGinty’s Goat there, Andrews’ remit was far wider.

At one stage he was one of the most familiar faces on British television — sports commentator, quiz chairman, interviewer, host to show business personalities, chairman of panel shows. He never descended into paddywhackeray — as a broadcaster he carried the public with him through charm, and a total command of whatever brief he was involved in.

It was as host of This is Your Life that caught the public’s imagination, turning Andrews into a national celebrity — there was no doubt that the British public had a remarkable affection for the Dublin man

Eamonn Andrews was the first Irish castaway on Desert Island Discs back in 1958. He chose no Irish records, his closest being Panis Angelicus performed by the Irish tenor John McCormack. But then Andrews was always aware of the anomalous position he held — he was an Irishman in a largely unwelcoming Britain. Back in the 1950s Irish people were routinely discriminated against, regarded as an underclass by a large proportion of the British populace, and the butt of offensive jokes everywhere from the pages of Punch to the local pub. Yet Andrews somehow managed to leap over that barrier and found himself one of the most popular broadcasters in Britain. He neither played the ‘Oirish’ card, but neither did he overtly espouse Irish causes or indeed Irish culture. And in his public life he was always circumspect to a fault.

On one occasion a researcher for a magazine programme phoned Andrews’ secretary to find out if the broadcaster would like to relate “any amusing anecdotes” on the programme. The secretary replied, “Oh, I’m sure Mr Andrews wouldn’t want to be involved in anything as risqué as an anecdote.”

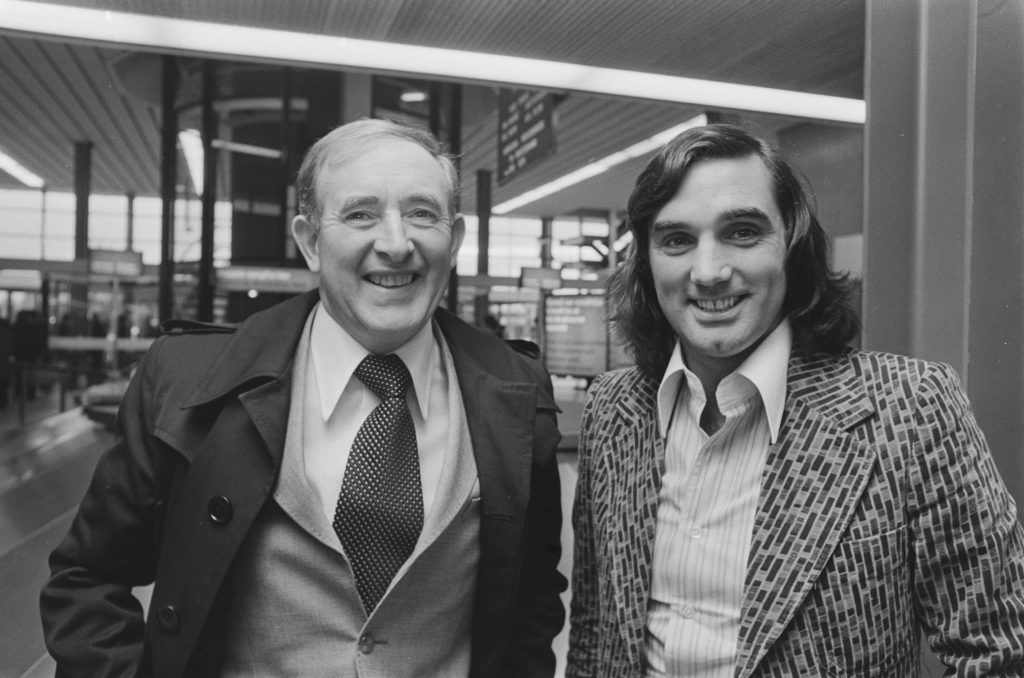

DIVIDED OPINION: Danny Blanchflower (L) who said No to Eamonn Andrews, and George Best who said yes to an appearance on This is Your Life (WIkipedia Commons)

DIVIDED OPINION: Danny Blanchflower (L) who said No to Eamonn Andrews, and George Best who said yes to an appearance on This is Your Life (WIkipedia Commons)

Unsurprisingly, then, Andrews felt that the best course on Desert Island Discs was to confine his choice of records to light classics and popular standards. He was probably right, because, in truth, the broadcaster did have something in the background that was probably well worth keeping quiet about in Britain. Eamonn would not have wanted it known that the Wolfe Tones recorded in his studios in Dublin. At the height of Eamonn’s fame in Britain, the Wolfe Tones were recording the likes of Up The Rebels, The Dying Rebel and the Rifles of the IRA in Eamonn’s Henry Street studios. Needless to say, none of the Wolfe Tones’ songs featured on the broadcaster’s Desert Island Disc list.

Andrews was born in Synge Street, Dublin on December 19, 1922, and educated at Synge Street CBS. He began his career as a clerk in an office — the Hibernian Insurance Company paid him £1 a week

But his interests lay elsewhere — in boxing, journalism and broadcasting. He was a keen amateur fighter — at 6ft 1in, Andrews weighed 13st at his peak so he largely fought in the light heavyweight or middleweight divisions — he won the Irish junior middleweight title in 1944.

In journalism his first paid article was in Dublin’s Evening Herald.

LIFE STORY

It was This is Your Life that caught the public’s imagination and established Eamonn Andrews as a national treasure. At its peak, 20million viewers tuned in to see who Eamonn would ambush for his show — although viewing figures were more regularly around the 10million mark.

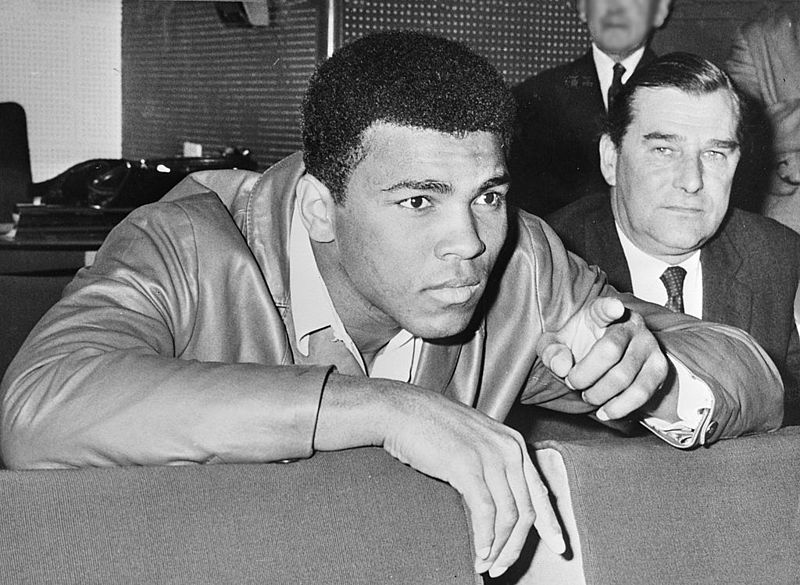

In the early days Eamonn Andrews went to great lengths to catch people unawares. Helped by his training as an actor, he would don various disguises and surprise potential guests. He was tied up in a sack before pouncing on personality magician David Nixon; he hid behind a door to corner Muhammad Ali; he donned air stewardess’s garb to ambush Shirley Bassey; pretended to be a wine waiter to nab David Frost, and ‘became’ an astronaut to land Patrick Moore.

The first person to turn him down and refuse to appear on the programme (there were only three) was Belfast man and Tottenham Hotspur footballing legend Danny Blanchflower.

Originally the show was broadcast live, but this ended in 1980 after Alan Minter wouldn’t stop swearing it was decided to pre-record it.

At school he’d shown promise by winning prizes for essay writing. Look back at this time in his life he said, "Convinced I had the talent to earn money from writing, I spent more and more time knocking out short stories and articles. And whenever I read of a competition that had a literary flavour, I would hide myself away in the parlour and write furiously to try to win a prize."

His first commentating job was at Radio Éireann at the age of 16. He landed the job through a mixture of chutzpah, genuine knowledge of sport, and a spot of luck — right time, right place.

In his early days of in Dublin for Radio Éireann he pulled off a feat that was perhaps unique in broadcasting history — he was both commentator and competitor. On one celebrated occasion he had four minutes to finish commentating on one bout and get into the ring for his own fight.

During this time in Dublin Andrews even tried a spot of treading the boards. He studied acting under Ria Mooney at the Abbey Theatre, and took part in plays on Radio Éireann. His own play, a solemn work entitled The Moon is Black, was staged at the Peacock. By all accounts it wasn’t particularly good and certainly wasn’t successful.

Meanwhile Andrews was still boxing and broadcasting. But it seems likely that noises from Radio Éireann bosses caused Andrews to curtail his boxing career in favour of broadcasting. It proved a wise decision.

The world of insurance had long been left behind and Andrews was working fulltime as a sports commentator on Radio Éireann. After almost a decade of doing this fulltime, he crossed the Irish Sea for a job as sports commentator on the BBC Light Programme.

While most of his work was carried out in Britain, Andrews spent a lot of time in Ireland. He was Chairman of the RTÉ Authority from 1961-66. As Chairman of Radio Éireann, he compered Telefís Éireann’s opening night on New Year’s Eve 1961. And of course he popped in to his studios. He tended to work in London from Monday to Thursday and lived in Dublin the rest of the week.

FELLOW BOXER: Muhammad Ali - a guest on This is Your Life (image WIkimedia Commons)

FELLOW BOXER: Muhammad Ali - a guest on This is Your Life (image WIkimedia Commons)

Eamonn Andrews died in 1987. He had recorded his last edition of This Is Your Life six days previously on October 30. Andrews died of a progressive deterioration of the myocardium, the main heart muscle, in Cromwell Hospital in London.

He is buried in a hillside plot in Balgriffin cemetery near his house in the village of Portmarnock.

Whole dissertations have been written about the reasons that Irish broadcasters have been so successful in Britain. It appears to be a unique situation; nowhere else in Europe have the same numbers of broadcasters from a neighbouring country achieved the popularity or ubiquity to rival that of Irish broadcasters in Britain. One reason often given is that the Irish accent is classless in Britain, a notoriously class-ridden country. Although class divisions, of course, exist in Ireland, it is not nearly as marked as it is in Britain. Go into a shop in Cork, and the person behind the counter won’t sound much different from Taoiseach Micheál Martin; our President probably sounds pretty much the same as the postie who delivers the mail to Áras an Uachtaráin.

This classlessness it is argued, makes Irish broadcasters acceptable to huge swathes of the British public.

Whatever the reason, whatever the secret, Eamonn Andrews stumbled on it in the last century and, arguably, paved the way for many others to follow.