IN the summer of 1998 I had just turned 11 and was sitting in the passenger seat of my Dad’s car when something happened that would set him off on a course of investigation for several years.

An intimidating authoritarian voice boomed from the radio “James Haskins, you are sentenced to death by hanging”. My Dad nearly crashed the car.

There aren’t many Haskins in Ireland. Not only that, but my Dad’s name was also James Haskins. So was my grandfather’s, and his father’s before that.

It was an ad was for Wicklow’s Historic Gaol, which had just opened as a tourist attraction.

My great-great-grandfather had come to Dun Laoghaire from Wicklow in the nineteenth century but our antecedents prior to that were a mystery. That year was the bicentenary of the 1798 Rebellion and my Dad wondered if James Haskins had been some kind of revolutionary hero.

He eventually paid a visit to Wicklow gaol to corroborate this theory, but what he discovered sent him back to the drawing board.

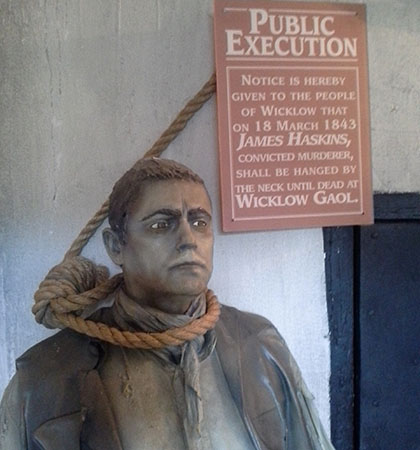

James Haskins had been chosen for the radio ad because he was the last man to be hanged at Wicklow Gaol, on the 18th March 1843. He was not a hero.

The crime that cost him his life was the murder of a farmer and small time moneylender named John Pugh from Rosnastraw, near Tinahely.

Dad persevered with his refocused quest to find out if we could be related to the last man hanged in Wicklow Gaol, buoyed by the strange kind of cachet that comes with having a historic murderer in the family.

Last month the National Library of Ireland launched a web repository of Catholic parish records from the 1740s to the 1880s (registers.nli.ie). The new website received huge interest from Irish people and Irish diaspora, with 185,000 unique visitors from 150 countries in its first week alone.

In recent years other extant records have been made available online through free resources like www.irishgenealogy.ie and the Mormon-run familysearch.org along with subscription sites like rootsireland.ie which claims to have over 20 million Irish records.

But in those days before digitised records, researching your family history was a much more laborious and time-consuming pursuit. Dad combed through church archives - baptisms, marriages and deaths – and over several years gradually began to form a fragmented picture of our family tree.

On weekends we would drive to obscure church graveyards, scraping the moss from old headstones to read the names chiseled into them long ago. We called to the homesteads of old-timers with long memories, trying to piece together the story of James Haskins, and how it might connect with our own story, but the records just didn’t exist to conclusively prove whether or not this man was our ancestor.

These are my fondest memories of that period of my childhood. When I remember my Dad, I think of those days as his co-detective, how he respected my opinions and theories as equal and took me on that journey with him.

My Dad passed away in 2006. One of the things you realise when a parent or a grandparent dies, is how much knowledge dies with them.

Last year it troubled me that for all Dad’s work tracing our family history – I could only remember vague scattered bits of it, but nothing about how it all joined up. I got nostalgic for that summer 17 years ago and wondered if those old people we’d spoken to about the murder were still alive. And if they weren’t, had the story died with them?

I also think there’s something in us that makes us want to go further than our parents. So I decided to try and finish what my Dad had started and solve this cold case in our family history.

I began by retracing the places I had visited in my childhood, discovering long lost relatives who welcomed me into their homes and farmers who remembered meeting my Dad all those years ago.

There were many dead-ends along the way too – but each little breakthrough spurred me on; like finding Willie Stedman, an 89 year-old farmer from Tinahely.

A tall, proud man, Willie still drives machinery at harvest time and has a voracious appetite for stories and local history. When Willie was “only a chap”, he conversed with the old men and heard their stories, which he can still recall with remarkable clarity.

Willie unraveled the story of the 1843 Pugh murder for me, complete with the names of locals who had witnessed it: “There was another house quite near Pugh’s house, Dan Loughlin and his wife. They were very old people. She heard some noise in the night and she says to the husband ‘Something’s going on at Pugh’s, someone could be getting murdered’. ‘Go out, so’, says he, ‘And they might murder you too!’ And they never looked out, but sure enough it was the case.”

My own journey took me from the cells of Wicklow Gaol, back and forth across the county, on what had the potential to be a proper wild goose chase. At times I felt like a tourist in my own country, knocking on strangers’ doors and asking if they’d ever heard of Haskins. Some of the strangers actually shared my surname and invited me into their homes for tea.

The quest finally took me to the House of Lords in London where I met self-described “milkman from County Wicklow”, Lord Christopher Haskins.

Chris agreed to have his DNA analysed by a company called Ireland’s DNA and to have the results compared with mine.

A loss of knowledge to passing generations motivated me at the outset. I hadn’t considered that knowledge can also be gained with time, and the information that ultimately answered the question of whether I am related to the last man hanged in Wicklow Gaol was provided by scientific technology unavailable even ten years ago.

On hearing the results, instinctively the first person I wanted to call and share the news with was my Dad.

Listen to the full story on www.rte.ie or by downloading the RTE Doc on One app for iPhone and Android or by podcast on iTunes