“TODAY’S film stars all look so alike,” says Toni Delany, the veteran make-up artist and stylist who worked in the movies for three decades.

During that time Dublin-born Delany witnessed, at near hand, the shift from the old Hollywood faces that showed distinctive individuality, to the big names of our current day, who perhaps lack for a certain uniqueness of character.

For Delany, some of the magic has been lost along the way. “For me to have Fred Astaire in my chair each morning,” she gushes, “now that was quite astonishing.”

Delany’s recently published memoir tells of her time working in cinema and television, painting the faces of star performers and, literally, making them look right for the camera.

Delany’s book, titled Made Up: Tales of an Irish Make-up Artist in Film, gleefully evokes memories and insights on her extensive career in the film industry.

The cover of the book shows her on location applying delicate touches to Sean Connery, but she worked with (or perhaps worked on) a long list of top ranking actors, including Richard Burton, Daniel Day- Lewis, Vanessa Redgrave, Helen Mirren and Pierce Brosnan.

“The book took about three years to write,” Delany says. “I did not consider it seriously until it was nearly finished. The best thing was the memories it brought back of people and places.”

One sense that becomes apparent in her effusions on working with film actors is of having seen herself in a privileged position.

Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman starring in Far and Away

Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman starring in Far and AwayDelany’s career began in the early 1960s, when Irish television broadcasting was in its infancy and Ireland had very little cinematic output worthy of mention.

She started her film work after the so-called ‘Golden Age of Cinema’, when film stars were deemed modern-day mythic gods and goddesses, and which probably ended with the tragic death of Marilyn Monroe in 1962.

Nevertheless, Delany’s enthusiasm still gives the impression of having been involved in movies when they were taken as a glorious and mysterious form of magic.

Delany made up Fred Astaire on French director Yves Boisset’s decidedly odd existentialist piece, The Purple Taxi (1977).

Astaire wished to reinvent himself as a performer in a different light at the time and was cast as an Irish village doctor. (Boisset’s illusive movie has a cult following, including its own Facebook page.)

Though she worked with Astaire long after his Fred and Ginger heyday, Delany describes him as “the most amazing actor”.

Yet despite her feelings of high regard toward those whose faces she expertly made up to fit the roles they played, she also retains a sense of grounding.

The actors that viewers see as gilded “stars” are still professionals just doing their jobs.

“Making up actors at dawn is a great leveller,” Delany says, “they become just people at that hour of the morning.”

Even so, Delany’s memoir doesn’t include revelations of sordid secrets or juicy scuttlebutt. Thoughts on her craft also illustrate how film-making is a phenomenon of many technical skillsets.

The make-up department is just one area in which a great deal of imaginative trickery is used to make things appear “natural”.

When working on Far and Away (1992), Ron Howard’s epic melodrama of Irish emigration to America, Delany used a team of 16 make-up artists in recreating the ordinary everyday crowd scenes set on the 19th century New York dockside.

“Each extra had to be checked individually for period looks,” she recalls.

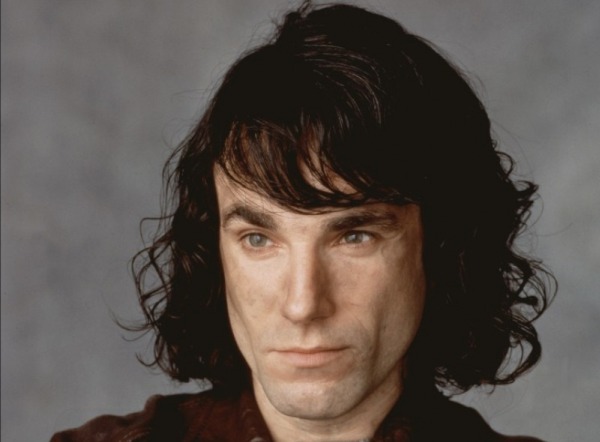

Toni made up Daniel Day-Lewis for the 1993 film In The Name of the Father

Toni made up Daniel Day-Lewis for the 1993 film In The Name of the FatherIt’s common for movie viewers to stop taking notice of the end credits about halfway down the cast list.

"If we observe the name of the make-up artists, it’s usually because we’re waiting patiently to get the title of that song we liked that played over the action.

But it’s perhaps worth recalling that Louis B. Meyer opined in the early days of Hollywood that artistic designers and costume makers were worth more to the film industry than all the “dime-a-dozen” actors, writers and directors.

Delany was also active in establishing the film technicians union during the 1970s and, as with so many in the industry, she sees film as her way of earning a living.

After retiring from location work in the late 1990s, she helped set up courses at the Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Dun Laoghaire and seems to have transferred her zeal to her students.

To those aspiring to a career in film, in whatever capacity, Delany dispels any illusions of glamour. “You have to be prepared to work out of doors, in all weathers and conditions,” she advises, “and sometimes work very, very long days.”

Notwithstanding her many accolades, when Delany is asked to name what she sees as her finest accomplishment, she laconically answers: “Surviving!”

In these digital times when we are all, potentially at least, filmmakers or photographers to some degree and everyday devices, from iPads to cigarette lighters, are fitted with highdefinition cameras, film has inevitably become somewhat demystified and shed some of its golden coating.

So it’s no bad thing that Delany’s colourful, insightful, graceful and grateful memoir recalls a time when cinema was a technology only for experts and a spectacle always gazed at in wonder.

Toni Delany’s Made Up: Tales of an Irish Make-up Artist in Film is published by Ashfield Press