BRENDAN Behan died of a combination of diabetes and alcoholism in March 1964. He was aged just 41.

By then he had been feted worldwide for such plays as The Quare Fella, The Hostage, and of course the book that started it all, Borstal Boy.

Fifty years on his standing as a writer is higher than ever; his plays are still being performed world-wide, and he is grouped with the likes of Joyce and O’Casey as being among the greatest Irish writers of the 20th century. Not bad for a boy from the Dublin slums!

Brendan was a house painter before he became a writer. Never a patient man, he only ever painted a wall once, and if you asked him to give it another coat you would be quickly told what do with yourself!

It was similar with writing; he hated pruning and editing; and having written the ‘thing’ he let others do the re-writes and editing. He said he wrote primarily out of ‘muraphobia’, the fear of painting walls, and that he drank out of ‘scriptophobia’, the fear of writing.

Hence his often-repeated comment that he wasn’t a writer with drinking problems but rather a drinker with writing problems.

His real name wasn’t Brendan but Francis, and he could read all of Robert Emmet’s famous Speech from the Dock by the age of six, probably a legacy from his father, who read writers such as Dickens and Thackeray to the children from an early age.

Brendan said he discarded the paintbrush for the pen because the latter was easier to write with. It has often been said that there are two types of writers in Ireland, those who beaver away at their desks all day and those who talk their masterpieces away in pubs.

Brendan was certainly more of the latter type, although he always claimed he stayed on the wagon while he was writing. Maybe. But I suspect he took Ernest Hemingway’s advice to “write drunk, edit sober”. Well, the first part, anyhow!

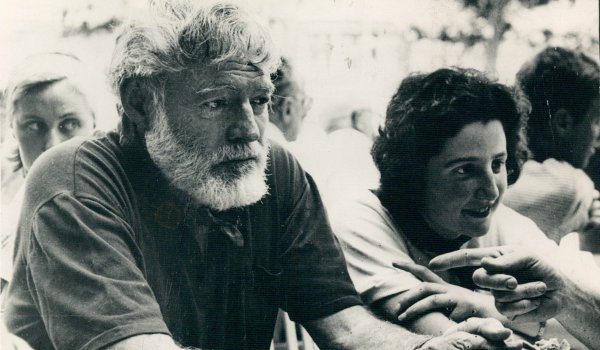

Behan with Beatrice (right) in 1959

Behan with Beatrice (right) in 1959Brendan was the king of the one-liners:

Reporter: What do you think of Canada Mr Behan?

Brendan: Ah, it’ll be grand when it’s finished.

Reporter: (at Madrid airport) What would you most like to see in Spain, Mr Behan?

Brendan: Franco’s funeral. (he was put on the next plane out of Spain for that!)

Reporter: What do you think of Ireland, Mr Behan?

Brendan: It’s a great place to get a letter from.

My play Brendan Behan’s Women look’s at his relationship with the two important women in his life, his wife Beatrice and his mistress Valerie Danby-Smith, who had a son, Brendan, by him shortly before Beatrice gave birth to their daughter Blanaid.

Brendan first met Beatrice when she was a 17-year-old schoolgirl, her father having brought him home from the pub one day. Brendan explains it by saying they were rained off at the building site where he worked and they had spent the afternoon drinking their “wet money”.

Cecil ffrench Salkeld, her father, liked a drink just as much as Brendan, and was a well-known painter and poet in Dublin literary circles, while her grandmother, Blanaid Salkeld, was a poet, dramatist and actress, who had published five books of poetry. Brendan “courted” Beatrice on and off for a number of years before they married in some secrecy in 1955.

Valerie Danby-Smith, was also a Dubliner, convent educated, and had gone to Spain to learn journalism in 1959. There, she was fortunate to meet Ernest Hemingway, who immediately took a liking to her and engaged her as one of his assistants.

There followed a glorious summer of bullfighting, boozing and cavorting in Spain, before she was whisked off to the Hemingway villa outside Havana, Cuba, where she continued assisting Ernest and his wife Mary with their literary enterprise. A little more than a year later Ernest blew his brains out and Valerie found herself in New York, where she met Brendan.

Brendan loved New York; it was the place, he once said, “where you were least likely to get bit by a wild goat”, and he would have lived there permanently if it weren’t for Beatrice’s concerns that it would acerbate his drinking problems. She had seen what had happened to Dylan Thomas there and she didn’t want a repeat with Brendan.

Brendan met Valerie there when she was hired to do some promotional work on The Hostage during its run. She became friendly with both of them, and it was when Beatrice had returned to Dublin, leaving Brendan alone in New York, that the affair began.

The fact that she had been very close to Ernest Hemingway before he shot himself fascinated Brendan; he saw parallels with his own life; the hard drinking, the health problems. Ernest had very high blood pressure, his eyesight was failing, and he, too felt he couldn’t write anymore.

He had also spent some time institutionalised at the Mayo Clinic, receiving electric shock therapy amongst other treatments – a fate Brendan was terrified would happen to himself. Hence his irrational fear of hospitals and his refusal to have sustained treatment.

Brendan was back in Dublin when he heard Valerie was pregnant. He was overjoyed; he loved children and he and Beatrice had been trying for years to have a baby without success. He hurried back to NY without telling Beatrice where he was going. When she eventually found out where he was, the rumour had spread that Val was having his baby. Beatrice then discovered she was pregnant herself, so she hurried off to NY to confront him.

Ernest Hemingway (left) with Valerie Danby-Smith

Ernest Hemingway (left) with Valerie Danby-SmithI had been fascinated by Brendan ever since I had read Borstal Boy as a teenager, and had already written two plays featuring him – On Raglan Road and Gorgeous Gaels – and the idea that the two women he loved were both pregnant by him – at more or less the same time – was a fascinating theme to write a play about.

Imagining what might have happened when they met was helped by the fact that both women had written books which covered the event, and although their versions were completely different, it is a playwright’s job to read between the lines and come up with a plausible scenario. That the fur was flying there was no doubt!

Brendan always had a story to tell, not realising that he himself was the greatest story of them all. His life was like a series of Shakespearean comedies/tragedies played out in the bars and bawdy-houses of Dublin London, New York and any other place he might wash up. The whole world was his stage without a doubt.

His plays have certainly had a renaissance recently, and there have been a number of new plays about him in this new millennium – yours truly being guilty of three of them! His books are still in print, and his witticisms are quoted as widely as Wilde and Shaw on the internet. Had he been able to receive proper treatment for his illnesses he might have lived for another 40 years. Who knows what his output would have been had that happened?

I will leave the last word with Brendan: “I respect kindness in human beings first of all, and kindness to animals. I don’t respect the law; I have a total irreverence for anything connected with society except that which makes the roads safer, the beer stronger, the food cheaper and the old men and old women warmer in the winter and happier in the summer.”

Brendan Behan’s Women by Tom O’Brien will run at Pentameters Theatre, 28 Heath St, Hampstead NW3 6TE from July 1-20. Tel 0207 435 3648