SIR Bob Geldof has maintained a reputation for versatility in his career.

The spotlight first shone on the Dublin native when his 70's rock band The Boomtown Rats reached number one in the charts when their debut single "Looking After No. 1" reached the UK Top 4o Singles Charts. The band cemented their place in rock history with follow up hits I Don't Like Mondays and Rat Trap.

Bob used the platform afforded to him by this mainstream success to express his humanitarian soul in the most international form. In 1984, with Midge Ure of Ultravox he wrote Do They Know It's Christmas? in order to raise funds. The song was recorded by various artists under the name of Band-Aid.

A year later, that was followed by Live Aid, a huge live concert staged simultaneously at the Wembley Stadium in London and John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia, featuring some of the biggest artists in the world. The event raised over £150 million for famine relief.

More recently, Bob Geldof has turned his attention to film (that is until he finds another passion to pursue).

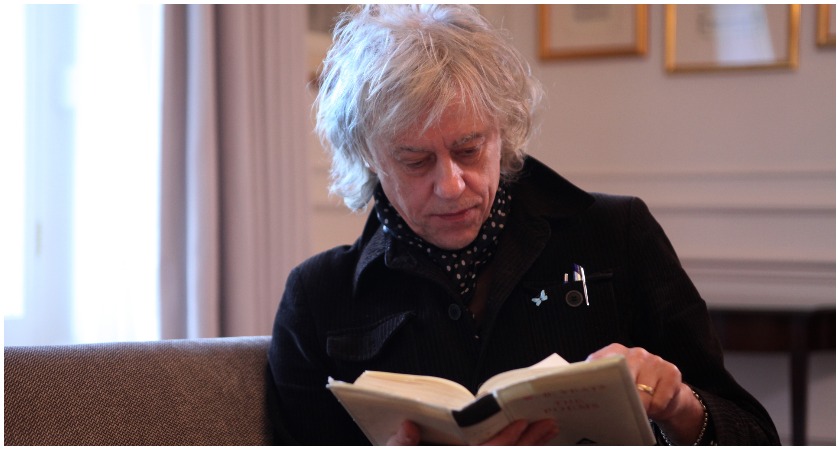

In A Fanatic Heart: Bob Geldof on W.B Yeats, he delves into the life story of the man he believes to have "invented and laid the foundational stones of modern Ireland".

Bob spoke with The Irish Post about why he was drawn to the figure of Yeats, how Yeats' experiences of being a young Irishman in London related to Bob's 100 years on, and he gives his take on what the great literary figure would make of the Ireland of today. Here is that conversation.

IP: Having watched the film, it was clear to me that you were completely engrossed in the life of this man whom you clearly have great admiration for. How much did you enjoy making this film?

BG: “Well, to be honest, I don't like doing television. It’s not natural to me. When you write a song you get an instant gratification but doing telly is always a personal argument for me…I’m not David Attenborough.

“With Yeats, I got to where I wanted to get to simply because when I began I didn’t quite know enough. I knew what my idea was going to be but as it unravelled itself, this guy became a monstrous hero and genius not just of course for Ireland but the poetry is for the ages and the music is universal.

"I think he is the central revolutionary character in the genesis of a modern Ireland. I think he is to Ireland what Shakespeare is to the English language and to Britain.

"From Ireland’s point of view, this is the man who invented and laid the foundational stones of modern Ireland."

IP: To this day his work is widely celebrated around the world. Why do you this is and what makes the work of somebody like Yeats stand the test of time?

BG: "Well, genius will always do that regardless of where you’re from. He is a clear Irish voice, but people elsewhere hear it in their own voice. That is achieved by a vast intellect. Yeats set out to write a poem as he said: “as simple as the dawn”. He wanted to write poems that anyone could understand – that the beggar on the streets of Dublin could understand.

"When he had that, he’d write it. That’s why it translates across the board, across all of humanity. And why it particularly throbs in an Irish soul. Because you hear Ireland when you read Yeats. That’s what happened to me aged 16. I had an English teacher who could not just recite but truly read poetry, and suddenly I heard this country that I lived in which was not being translated to me through the television. Suddenly here was Yeats and he was speaking to me with a distinctive Irish voice.

"I’ll give you an example of that - when I was 15 and 16 there was nobody at home to make me do my homework or make dinner so I stopped going home and started hanging around in the centre of Dublin, I linked up with the Simon Community, a homeless charity, and there I met men who had fallen out of the family in pre-divorce days, lost their jobs and fell into drink – schizophrenic men and women, prostitutes who were thin and impoverished young girls.

"They were very interesting people and I'd do the rounds with a flask of soup, and in a doorway there lived a woman named Mary who I thought was ancient but was probably about 40. I said to her: “look, Mary, you can be housed”. Lots of them wanted somewhere to live but some chose not to be rehoused. Mary was one of those who didn’t.

"I said to her why don’t you want to go and live somewhere cosy and comfortable instead of living in some doorway under some boxes and she said to me: “She never wanted to hear the slap of a utility bill on the tiled hall floor”.

"Now that is a specifically Irish rhythm and use of language so that you hear the sound and you can visualise a clear image.

"Take Yeats' quote: "To hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore". There's a universal understanding of what that man was looking at that moment. And to hear Mary speak is to understand what language means to the Irish. It is a direct emotive visual intellectual means of expression. It is not the utilitarian language of the British."

IP: In the film, it shows you standing at the lake where Yeats wrote that poem, and you actually heard the lake water lapping as Yeats described. That must have been a surreal moment.

BG: “You can see me standing there looking around in astonishment exclaiming “It is lapping”. I heard that sound in my head as Yeats did that day on the strand in London while he's walking along the grey cobbled street in November and he stops to look at a fountain in the window display of a shop and he wants to go home to be in Sligo.

As much as he is thrilled by the vast intellectual world London gives him, he just wants to go home to be by the lake where he can be in peace. It’s a great poem of exile which is why its universal. Anybody away from home can read this poem and connect to it. It is pure unadulterated, literary genius. It’s a ballad and a pop song and it is simple."

IP: The longer you’ve spent away from Ireland, has your appreciation of and interest in Irish literature grown?

BG: "No I’ve always loved it. I was always shocked by how this country produces language that can immediately be transliterated into literature or poetry or whatever. It always strikes me as odd.

"I route it back into the fundamental time of the late 1800s coming into the 20th century. I reject the simplistic and naïve notion that the foundational moments of the Irish modern state is what happened in the GPO in 1916. I think it’s the original sin of the modern Irish state. I think the foundational moment is the year zero. It's the famine.

"I've lived and travelled and worked amongst famine. When I was making the film and I spent time in the West, the ghost of that great devastation swum around me. Everything had gone. The culture, the families, the land. I thought of the great movement out of the cities of Belfast and Dublin. Impoverished people speaking this unknown language. A Victorian report of the 1900's stated Dublin was the worst slum in Europe at the time, worse than Warsaw. You don’t read much about this.

"Out of this migration came this understanding, particularly from Yeats, that you are not a defeated people. Go back to before all of that history of failure which we love to repeat. Our heroes are just as great as the Greek legends. Still to this day the fairylore is incorporated into the culture of that part of the country. They recorded it all because they understood that unless you knew who you were as a people, there could be no now and no future. Once you understood who you were, you could build the constitutionalism on which the society could build itself afresh. That’s what they achieved."

"Yeats said it wouldn’t be understood until 50 years after his death. Fifty years on from the day he died, we elected a woman as president who was a human rights activist and lawyer. That was Yeats' vision of Ireland. He understood it to be a modern and intellectual society. He was the one who wrote it and made sure that it could happen."

IP: Where does nationality come into play when it comes to the work you’ve done in your career and the work you continue to do today?

BG: I hate nationalism. I absolutely loathe it. I am deeply uncomfortable with it. I don’t see any good coming out of it. Patriotism is completely understandable and healthy but evil men and women with an unconvincing vent curdle that natural empathy into a political philosophy and that can be very very very dangerous. We've seen it in our time in our own country and we see it in Brexit Britain now. I am deeply uncomfortable with watching Johnson, Rees-Mogg all of these people and what they’re saying and doing. They revert to the language of the ideologue. This is what this leads to. We have to be really careful because it leads to blood.

"I was out on the river trying to stop Farage and the Remainers from coming up the Thames during the Brexit referendum and I was with my friend Brendan Cox with his two little children. The next day his wife was murdered by a far-right British nationalist. Somebody deluded into this great bloodlust committed this crime. The vertigo of self-sacrifice as Yeats put it. It is this second coming that is terrifying. We have to be really careful time and again. My film was to be a corrective against what I anticipated to be the awful Korean type kitsch that would revolve around the 100 year anniversary of the 1916 rising because the 50th anniversary was so awful for me when I was 16."

IP: What do you imagine Yeats would make of the Ireland of 2018?

BG: "Yeats in his head was living in the Ireland that exists today. I'm very comfortable with the Ireland of today, but I felt alien in the Ireland I grew up in. Yeats introduced me to the actual Ireland.

"We know that once he has set his cap to creating modernity, bringing foreign plays and modern arts to Ireland. He railed against the censorship that was a part of the Catholic coup d'etat. He railed against the divorce laws which they brought in. Now, we got rid of that but it kept all of our geniuses out of our country. We had no voice during this period of cultural claustrophobia until we broke out of it many years later.

"So, the Ireland of today he would totally understand. As he said himself, it'll only be understood 50 years after his death. He died in 1939 and in 1989 we get our new Ireland.

"I will vote for a repeal of the eight amendment. In this case, Yeats would be totally engaged in it. He would understand it. This debate isn't like the equality of marriage. That was different. If two people want to get married, who cares! If you want to get married go and do it! I was brought up in another time when that was considered weird, but now we consider it absolutely normal.

"This referendum is different. We need to be more respectful of each other's point of view. I would hope that somebody who comes at it from a religious point of view or an instinctive point of view can respect my point of view. Hopefully the side I will be on can look at the argument in the same way. I think Yeats would be the side I'm on. Also, I think he would completely understand the other point of view. I don't have a vast intellect but this man could encompass any point of view either for or against. In this case, however, I think he'd be for it."

A Fanatic Heart: Bob Geldof on WB Yeats is available now on DVD.