RADIO CAROLINE was the first of the British offshore radio stations.

It was started by Irishman Ronan O’Rahilly and without him there would have been no Radio Caroline, but what led O’Rahilly to start this radio revolution in Britain?

O’Rahilly had legitimate Irish Republican credentials. His grandfather was Michael Joseph O’Rahilly, shot by British soldiers while taking part in the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin.

Married to an American, Ronan’s father, Aodhogan, also had an interest in the politics of Ireland; he stood for election to the Dáil, the Irish parliament, in 1932, but failed to win a seat.

As an educated engineer, he became a successful businessman with involvement in the peat and building industry and forestry. Ronan O’Rahilly came from this wealthy background.

Born in 1940, O’Rahilly took pride in being a rebel; he claimed that he was expelled seven times from school.

He moved to London at the start of the 1960s and quickly got to know the people who frequented the coffee bars of Chelsea.

It was a place to be hip and cool, and with his charm and good looks he soon became one of the coolest in the Chelsea set.

He moved to London’s club land in Soho, running the Scene Club in Ham Yard off Great Windmill Street.

The Scene Club was dark, cramped and narrow, with a small bar, what passed as a dance floor and a stage too small for anything other than a DJ who had to make room for live bands and their equipment; consequently, it was very loud.

Ronan O’Rahilly was also the manager for a number of artists at this time; he was certainly working with harmonica player Cyril Davis and legendary blues musician Alexis Korner.

Another of Ronan’s protégés was blues singer Ronnie Jones, an American serviceman based in Britain: Well, he started out trying to tame Alexis Korner. He invested in suits and stuff, which the guys took and laughed about.

Ronan knew how things were done; he was very hip, he really fancied himself, but he had a lot of ‘get up and go’ and verve.

He helped to launch The Animals, but he and the manager had a split up and he always felt slightly resentful that he didn’t get a slice of The Animals – but he was there at the birth.

Keyboard player and vocalist Georgie Fame had a residency at the Flamingo Club and he also performed at the Scene, and it was Ronan’s attempts to promote a recording of Georgie Fame that, he claims, led him to start a radio station: “I can remember well going round with an acetate of Georgie after I’d discovered that the BBC wouldn’t play it at all because it wasn’t on EMI or Decca, and I suddenly realised that the whole thing was locked up.

I remember sitting with the head of Luxembourg and he had two of his colleagues in the office with him and I said, ‘here’s the acetate. How many plays can I get, will you play this?’

“I knew I needed airplay in order to get the thing to function and when I’d finished rabbiting about how many plays I’d get, there was spontaneous laughter.

The idea that somebody could walk in and believe they could get a recording played …and then he pointed out all these boards on the wall and there was EMI Show, Decca Show, EMI Show, Decca Show all listed and I said, ‘do you mean to say that every record I’d ever heard on Luxembourg was paid for?’, and he said, ‘you’re absolutely right. We’re booked up for five years’.

I said, ‘well, it looks like I’ll have to start a radio station of my own’, and with that they became very unhappy and they said, ‘you can’t do that’ …. I said, ‘well why not? You’ve done it.’”

Ronan has said that he was aware of other radio stations broadcasting from ships, in particular the Voice of America and the Dutch Radio Veronica, but now there were two would-be radio operators chasing the same dream.

The question that many have puzzled over is who came up with the idea first? Allan Crawford always maintained that it was him.

Armed with all the facts and figures needed, however they were obtained, O’Rahilly set out to start a radio station of his own. One of the few with whom Ronan had shared his idea was another Chelsea character, Christopher Moore.

Ian Ross shared a flat with him:

“I’d only recently known Chris. I was 19 and had come to London from the family home in Haslemere, but we became great friends and shared a flat together in Milner Street, Chelsea. Chris was a hustler, a sort of Kings Road cowboy that seemed to exist in those days. They’d sit in the Kenya coffee bar in Kings Road and pull birds and drink cappuccino; that was Chelsea in 1963.”

Ian Ross had a very wealthy father, a financier in the City, who owned the Jenson car company and had interests in numerous other businesses, including a London bank and the Buxted chicken brand:

“In 1963 dad was 63-years-old and still operating in the City with his chums, who used to have lunch and do deals. These were people who had umbrellas and wore bowler hats, though my dad didn’t.”

Ronan O’Rahilly needed to finance his radio station and the money he needed was heading straight in his direction:

“This was spring 1963, Chris knew Ronan and he said, ‘there’s someone I’d like you to meet, you’ll really like him, and he’s got this idea.’ We went to the Kenya, waited for ages for this guy to show and then this little leprechaun arrives, ‘How’s it goin’? How are ya?’, that sort of thing.

In those days you just didn’t speak to people like that; everyone was cool and didn’t speak to one another. I’d never met anyone like him; he was most entertaining, and everything he told me was pretty much the opposite of how I’d been brought up.

If you asked Ronan what he did, he’d say he was in the ‘why not’ business.

Chris and Ronan knew perfectly well that I was the complete lamb to the slaughter, a rich dad, and what they didn’t know, a rich dad who was prepared to do almost anything to find me an occupation in life other than crashing cars and getting drunk.

“We met again later the same day at the Carlton Tower, there was a bit of corridor and he’d set up a sort of headquarters there, so you’d appear and he’d be there with his documents and his whole bulls**t and you’d think … yeah …so we met again and I had my car downstairs, it was an MGB and he said, ‘don’t worry, I’ll drive’.

He drove my car at about 180mph all the way to Haslemere, with me in the back and Chris in the front and my dad’s there looking annoyed. He was a New Zealander and he had an ambivalent attitude towards the English upper classes. He used to have to deal with them every day, yet he wasn’t one of them; he was an outsider, a complete outsider.

There was something about Ronan that he immediately really liked, he just loved the guy, and I think they had some common bond in being anti-establishment – but his friends that he rang up that evening, Jocelyn Stevens and his father-in-law, John Sheffield, were very much the establishment, the absolute figures of the establishment.

“The money was delivered; we got the cash. I think we got it from the bank and we ended up with a suitcase with £150,000, which in those days was a fortune, a huge amount of money and I know it affected us all in the same way, me, Chris and Ronan. We went to mine and Chris’s flat and we just destroyed the place, we threw the money in the air, we danced around the place, we went crazy.

We were going to start a radio station.”

Ronan had his hands on enough money to bring his dream to fruition. The grandson of an Irish Republican fighter, John Sheffield (a descendant of the Duke of Buckingham) and his son-in-law Jocelyn Edward Greville Stevens, made an unlikely alliance.

Stevens was a flamboyant Old Etonian. He had inherited around £1million from a trust set up when his mother died shortly after his birth. With the finance in place, work started on setting up the radio station.

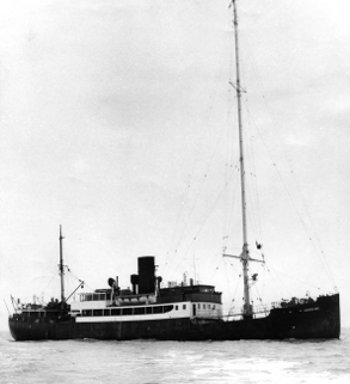

The task of finding a suitable ship was obviously top priority. Chris Moore was despatched to Holland to buy a ship for the radio adventure:

The task of finding a suitable ship was obviously top priority. Chris Moore was despatched to Holland to buy a ship for the radio adventure:

“Chris went to Rotterdam with 20,000 quid in cash to Rotterdam and buys this really great ship. She was a beauty and I remember when Chris got back, we were in Ronan’s flat, we’d bought the ship, laughing and giggling, the phone rings and it’s John Sheffield, and he’s the most serious, conservative, important guy you could meet and he starts by asking Ronan what’s going on?

‘Well, we’ve bought a ship John. It’s a beautiful thing’, so John asked, ‘what kind of ship?’ so Ronan puts his hand across the mouthpiece and says, ‘he wants to know what kind of f*****g ship it is’, ‘err John, Chris tells me it was some kind of ferry boat’. ‘What … a ferry boat!?” was the response, so Ronan says, ‘if you think about it John, there are a lot of inland waterways in Holland!’ and he put the phone down. We were crying with laughter.”

Radio Caroline: The True Story of the Boat that Rocked by Ray Clark is published by The History Press.