‘WASH your hands, wash your bloody hands!’

That is the command, simple yet urgent, that means the difference between life and death in Dr Semmelweis, a compelling new play which has just transferred to the Harold Pinter Theatre in London’s West End.

The tale, written by Stephen Morris with Mark Rylance - who also holds the leading role in the production, takes us back to mid-19th century Europe, where hospital deaths are rife in a world which has yet to identify the existence of bacteria or viruses.

Ignaz Semmelweis, a young Hungarian doctor, graduates from medical school and finds himself in a position at the Vienna General Hospital, which is at that time the largest hospital in Europe.

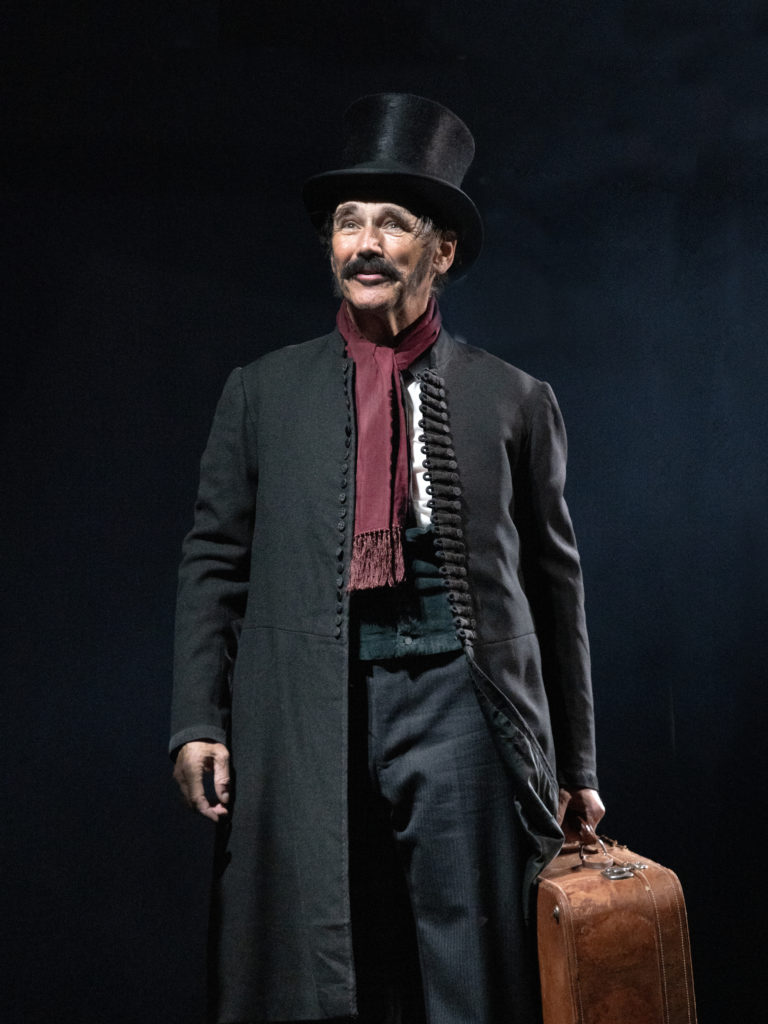

Mark Rylance plays Dr Semmelweis in the production at the Harold Pinter Theatre (PIC: Simon Annand)

Mark Rylance plays Dr Semmelweis in the production at the Harold Pinter Theatre (PIC: Simon Annand)Located in the maternity wing, he quickly becomes aware of the extraordinarily high rate of deaths due to what was then termed ‘childbed fever’ – where healthy mothers, who deliver healthy children, die within days of giving birth. A tragedy often followed by the death of their child too.

For Semmelweis these deaths, which over the years had accumulated into many thousands, must be accounted for.

Telling a rather shocking and largely unknown true story, Dr Semmelweis lets us all in on the horrors that befell maternity wings around the world before this radical young medical man set himself to finding a solution to the problem – or rather an understanding of what was happening.

Ultimately - eventually - he found those answers.

Mark Rylance as Ignaz Semmelweis and Felix Hayes as Ferndinand Van Hebra (PIC: Simon Annand)

Mark Rylance as Ignaz Semmelweis and Felix Hayes as Ferndinand Van Hebra (PIC: Simon Annand)Semmelweis learnt that doctors who did not wash their hands before dealing with their patients could effectively kill them by carrying infections between them.

The idea of basic hygiene practices in hospitals was born.

It all seemed so simple once Semmelweis had found the answer, but the importance of handwashing was not a theory that was going to be easily sold to his peers.

Firstly, experienced doctors didn’t like to be told they were killing their patients.

Secondly, physicians across Austria would not stand to be lectured by a person from Hungary – a nation they deemed inferior to their own at that time.

Throughout the play Semmelweis is haunted by the ballet-dancing ghosts of all the mothers who have died (Pic: Simon Annand)

Throughout the play Semmelweis is haunted by the ballet-dancing ghosts of all the mothers who have died (Pic: Simon Annand)So, as depicted so beautifully in the play, which is directed by the keen-eyed Tom Morris and features an emotionally evocative musical backdrop provided by the London-based Salomé Quartet, Semmelweis’ story goes far beyond his medical discovery.

It is the story of a man haunted by his findings and the fact those in the higher echelons of Europe’s medical society would ridicule him rather than believe them.

It is the story of a man haunted by the ghosts of the many women and infants who had died and who would continue to die while the medical world shunned his revelation.

Dancers keep the brutal reality of the horrors of 'childbed fever' brimming at the surface of this play

Dancers keep the brutal reality of the horrors of 'childbed fever' brimming at the surface of this playAnd it is the story of a man whose hauntings would eventually see him descend into madness.

Rylance is captivating as the brilliant yet growingly disturbed Semmelweis.

He appears to age right before your eyes across the two-act play as the ghosts that haunt the auditorium continue to present themselves to him.

Putting out a similarly powerful performance alongside Rylance is Irish star Pauline McLynn.

Sligo-born McLynn, a formidable presence on any stage, is perfectly cast as the hard-working maternity nurse Anna Müller in the production which transferred from the Bristol Old Vic this month.

Pauline McLynne as Anna Müller and Jude Owusu as Jakob Kollectschka (PIC: Simon Annand)

Pauline McLynne as Anna Müller and Jude Owusu as Jakob Kollectschka (PIC: Simon Annand)An ally of Semmelweis, Müller, as a woman, faces her own demons in the patriarchal Europe of the nineteenth century.

Nonetheless she risks her own livelihood to support Semmelweis’ work, in order to save the lives of the women in her care. And in true McLynn style, there is comedy and pathos to be found in equal measure in her faultless performance, which comes with a tragic twist of its own.

To be fair, there are standout performances across this cast, with Jude Owusu as Jakob Kolletshcka a particular favourite - as much for his hilarious comic timing as his dramatic positioning as the key to Semmelweis’ ground-breaking discovery.

Standout performances across the cast include that of Amanda WIlkin as Maria Semmelweis, pictured here with Mark Rylance as her husband Ignaz Semmelweis (Pic: Simon Annand)

Standout performances across the cast include that of Amanda WIlkin as Maria Semmelweis, pictured here with Mark Rylance as her husband Ignaz Semmelweis (Pic: Simon Annand)Throughout this bittersweet tale the emotion, the importance of the work at hand and the lives of the many people lost brims close to the surface at all times.

There is a persistent tension in the room and that is largely due to the presence of ‘the mothers’.

This troupe of ballet dancing women, who represent all those who have lost their lives, appear in all corners of the theatre as well as centre stage, throughout the piece.

Their rhythmic dancing and chanting adds a sense of fluidity to the production that is not easy to achieve.

The movement is awesome to watch. It carries the weight of all the women who have died and makes Semmelweis’ descent into madness all the more understandable.

If this is all he can see, these ghosts who are so striking despite their positioning in the shadows, is it any wonder he lost his mind?

Sadly, Semmelweis’ ‘wash your hands’ instruction only began to be taken seriously by the medical world once he was on his own deathbed.

Even sadder is the fact that he, ironically, died from sepsis.

Dr Semmelweis is at the Harold Pinter Theatre until October 7. For tickets visit www.haroldpintertheatre.co.uk