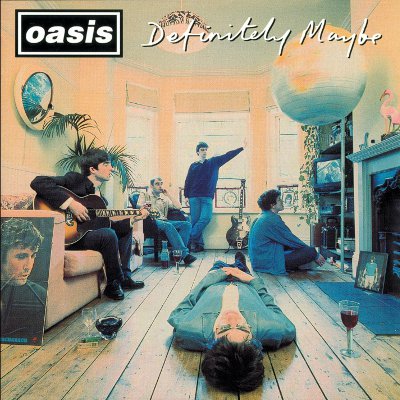

IN a year that has seen much consideration of Ireland’s cultural impact on British life, this month’s re-issue of Oasis’s classic debut, Definitely Maybe, offers solid evidence of its impact, 20 years on from the album’s original release.

It is a record that Noel Gallagher once described as “the sound of five second generation Irish Catholics coming out of a council estate” and true to that summation, Definitely Maybe is perhaps a work that could only have been made by a group of Irish Mancunians.

England saw a wave of Irish migrants arrive in the 1960s as cities such as Manchester provided essential labour during a construction boom.

The children of those immigrants would find new sub-cultural identities in football, fashion and pop music creating a vital and expressive contribution to the communal social fabric and culture of British life, particularly in the north west of England.

Inspired by the anti-establishment, anti-imperial post-Thatcher working class sensibilities laid down by The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays and Primal Scream, all five members of Oasis came from a strong Irish sub-culture.

Within the story was sibling rivalry, protective Irish mammies, absent fathers, hymns, rebel songs, support of Celtic and the Republic of Ireland, holidays in the west of Ireland and everyday post-industrial city life in backstreets Mancunia.

The rise of Oasis amplified the triumphs, humour and tragedy of Irish diaspora life to the nation.

Two decades on, Oasis founding member and rhythm guitarist Paul ‘Bonehead’ Arthurs confirms the significance of that background to the music, attitude and character of the band.

“He’s absolutely right in what he said,” Bonehead says of Noel’s comment. “That’s exactly what we were. We were five lads off the street. I get asked that a lot; ‘what is it about Manchester and Liverpool bringing out such great music?’ and my answer is the same, Celtic blood. It really is that, it’s the only explanation.

"It’s working class people from strong Irish backgrounds making music. My mother was from the west of Ireland in Mayo, a place called Swinford which is literally a few miles from Noel and Liam’s grandparents. My dad was from the North, about 30 miles south of Belfast.

"I went to very Irish Catholic schools, St Roberts in Longsight — everyone was Irish Catholic, we all went to church on a Sunday. I was an altar boy until I was 16 and it was time to hang up the cassock. The family had visions of me being a priest not a rock ’n’ roller.”

Was Irish music a conscious influence on the band? “I was talking about this with Alex (Lipinsky) who I’m in a band with,” he says.

“I put on Sweeney’s Men and he said it sounded like Oasis and The Stone Roses. If someone asked if we were influenced by that, well consciously no but subconsciously probably yes. You can hear their influence in a lot of other Manchester bands like Doves.”

Whether it is later episodes of Shameless or Benefits Street, the media often convey a feckless one dimensional vision of working class life. It’s fair to say Oasis were instilled with a resolute Irish work ethic and for the most part the five-piece held down steady jobs while rehearsing six nights a week. The nuts and bolts of the band were in place as early as 1991.

Liam Gallagher fronted The Rain with Bonehead, a plasterer, bassist Paul ‘Guigsy’ McGuigan, a call-centre telephonist, and drummer Tony McCarroll, a labourer. Noel Gallagher was the last to join. After stockpiling songs working for an Irish building firm, he would immediately take creative control.

Speaking shortly before Oasis split in 2009, Liam reflected on the period: “We had the music. From my point of view you have to try that bit harder with the Irish thing or if you’re Scottish; you’ve got to dig deep because everything revolves around England. My mates, the lads that were English had everything on a plate.”

On leaving school without qualifications Noel Gallagher’s mother Peggy asked him, “what is going to become of you? If music is what you really want to do, I don’t care if you stay on the dole but you better not let me down.”

A stint as a roadie for the Inspiral Carpets provided the budding songwriter with some vital insider awareness. Bonehead casts his mind back to his first recollections of the brothers.

“I knew Noel worked with the Inspiral Carpets and I’d see him at gigs and around the streets and boozers where we lived. I knew Liam before he joined the band, Liam was a young kid, and always a cool f**ker with the best clothes and when you’d see him he’d let on ‘alright mate’.

"I knew he’d make a great front-man. Peggy was everybody’s mate, she was a wonderful woman, still is — and no one is prouder of what Noel and Liam achieved with the band. She’s still here, there and everywhere with them; Queen Peggy.”

Oasis walked the same Manchester avenues and alleyways and came from the same Irish environment as The Smiths. Notably Johnny Marr also offered the band a helping hand. “He hooked us up with our manager (Marcus Russell) and invited us down to his studio,” says Bonehead.

“He was like ‘take this, borrow that, whatever you need.’ We loaded everything in the van. I’ve got to know all The Smiths apart from Morrissey; I’ve become close with Mike Joyce, we grew up two miles from one another. I didn’t know him then but we all knew the same people. It was an instant bond. Those guys are very much the same as us in many ways.”

The Chasing The Sun 20th anniversary edition of Definitely Maybe charts the evolution of the band. The songs and production took a number of attempts to get right and among the 33 extra tracks is the previously unreleased Strange Thing. You can literally hear the band’s self-belief grow as they shake off the indie/baggy era in exchange for a juggernaut of slice-of-life foot stomping, four to the floor rock ’n’ roll.

The bonus discs include a clutch of early sketch recordings and demos which indicate the effort and craft that went into delivering the finished versions, said Bonehead.

“Some of the early songs, like Strange Thing, have got a baggy beat. There’s more songs from that time that have that very Manchester sound, we were still finding our feet. There were times it wasn’t happening in the studio. We tried to record Bring It On Down, which was meant to be the first single, but we weren’t nailing it.

"Noel was in the control room and started writing down some words for what was to become Supersonic; he literally wrote it in minutes. He sang us the melody and wrote the words down for Liam and that was it; bang, recorded in a couple of hours.

"We then brought the song down to Maida Vale and played it to Alan McGee [Creation Records label boss] who was like ‘where the f**k did that come from?”

As momentum gathered throughout the summer of 1994, word of the band’s euphoric gigs swelled like a revival movement. Month by month they outgrew venues as Noel Gallagher enjoyed his most prolific period as a songwriter, never bettered since. Over the next few years his “stockpile” would fill airwaves, pubs, tenements and night-clubs with a run of anthems, said Bonehead.

“He had written Whatever and All Around the World years before Definitely Maybe. I remember saying to him, Whatever has got to be on the album. He had a vision for the band by that point and he didn’t want to record it. He decided to wait until we had a 40-piece orchestra. There’s a strings version on the re-release, it’s been great even for me to hear this stuff.”

Touring with The Verve was also fundamental to the band’s development. “We all looked up to The Verve, they were one of those bands that we aspired to and when we went out on our first proper tour it was supporting them. We learned a lot watching them on stage every night. That was an incredible experience in itself.”

The live versions of Supersonic from around that period sound very spontaneous, particularly Noel’s lead? “That happened sometimes especially at a good gig he extended the outro, he would literally make it up.” Were you never tempted to deliver a solo yourself?

“I went up the neck a few times and Noel would be like ‘nah man, keep it chugging’. Doing bar chords used to do my head in sometimes. I came up with the riff for Up In The Sky and he built the song around that one but generally Noel would arrive with the finished song.”

A number of the live recordings are from early Glasgow gigs. The city where they were discovered by Alan McGee was a stronghold for the band, sharing its diaspora link with Manchester and a well-documented support of Celtic.

“I always had a thing for Celtic because my dad was a die-hard supporter,” says Bonehead, “that was his team. My favourite player was Jimmy Johnstone. Every weekend he made a point of travelling up in the work van with a load of Irish lads, they would get pissed and watch Celtic. Glasgow and New York are my favourite cities in the world.

"Scotland in general was always really good, I remember we played this record company gig with reps flying around and we blew the place apart, that’s where the version of I Am The Walrus comes from.”

The special edition album repeats the inaccuracy that the recording was taken from the Glasgow Cathouse. Noel Gallagher previously explained that “it would look shit if you put ‘Live at Sony Seminar in Gleneagles’! We had a version of it from the Cathouse in Glasgow, which sounded quite similar but it was rubbish.”

The last gang in town currency that created Definitely Maybe wasn’t lost on Noel Gallagher either: “We were all from working class Irish backgrounds, we weren’t the best looking band in the world, apart from Liam who’s a good looking lad, but the point is anyone could have been in the band.”

As the structure of the band was slowly dismantled in favour of ‘professionals’ with the ‘right haircut’ they also conceded the folk spirit and idealism that captured the British public’s imagination. The first to go was drummer Tony McCarroll in April 1995. Although much lambasted by Noel Gallagher, it’s widely acknowledged the drums characterised the raw power of the now classic album.

“No matter what people say there was only one person who could have played drums on Definitely Maybe,” says Bonehead, “and that was Tony, it really was. If you strip away Noel’s guitars and listen to the rhythm section, it’s pure punk attitude in that record.”

Bonehead would quit the band himself in 1999 after a drunken argument with Noel followed by Paul McGuigan. “We were all f**ked by that point,” he says, “but I don’t think it hit me until prior to recording (Standing On The Shoulder Of Giants). I think he picked his moment (McGuigan). I didn’t expect him to leave as well.

Oasis were the first and last band since The Beatles to enjoy such widespread public esteem in Britain. Until their final split in 2009 they would routinely sell out stadiums across the globe. Rumours of an Oasis reunion continue to abound.

A recent exhibition, Chasing The Sun 1993-97, celebrated the early years of the band and a reunion of the original line-up would undoubtedly exhilarate a generation of fans whose lives were sound-tracked by the band’s early output.

Of late, Bonehead has returned to playing live with Phoneys & The Freaks. He has also re-established a solid friendship with Liam Gallagher. “I’m probably closer with Liam now than I ever was, we’ve played together at a couple of events recently.” Will you play together again? “I’d love to,” comes the reply. Is there talk? “There might have been.”

For now Paul Arthurs is staying tight-lipped but if he gets a call from the man he still calls “the chief”, he won’t stand in the way of what the public wants. In many ways he displays something of the Irish Mancunian steadiness that underpinned Oasis.

“I went to see Noel’s High Flying Birds in Glasgow,” he says, “and he dedicated a song to me. We’re not close, I bump into him from time to time but if he wants me to play a gig or whatever — I’m there.”

Definitely Maybe: Chasing The Sun Edition will be released on May 19