WHEN I think of my very first reaction when I was first sent the script of Samuel Beckett’s Not I with an audition time for the following day, I remember I took a massive breath.

I thought “Oh God… Beckett” and immediately tensed. I felt I would need to dig deep and root out some kind of mental pick axe to tackle this impenetrable intellectual mountain or take the short cut and call my brother who is an English professor.

But my brother thankfully didn’t return my calls that day and so with pressure mounting for the audition I just sat down alone and read.

And there it was, the inside of my mind shamelessly splayed open on the page. I saw waves of memory, corrections, interruptions, panic. I heard my isolation, pain, the hilarity of it, the judgment, “guilty of not guilty”, parochialisms from the streets of Athlone, “no sooner buttoned up his breeches”, Christian pieties that made me think of the nuns “God is love”, my mother’s “tender mercies”, what I heard was home.

It felt so close, so visceral, and so right and I felt propelled along by the inherent rhythm that seemed to be forcing me to speak this at speed. I also didn’t just hear one stream of consciousness but a waterfall, a cacophony of sounds.

He seemed to be taking me right inside the emotions themselves. But then I worried that surely I must be missing something… because everything I had heard about Beckett up until that point was purely intellectual and I was convinced that I was missing some important layer or something. It couldn’t be just so immediate, so guttural, so visceral like this, could it?

At the audition the director’s only note was that Beckett wanted this text to “play on the nerves of the audience and not the intellect” which is why he wanted it spoken at speed, at the “speed of thought”. I knew then that I was on the right path.

I had this confirmed when I was in the middle of rehearsals one day in Battersea Park.

One of the hardest aspects of Not I is the strain it takes on your memory. To be able to recall this tricksy, fragmented text at such speed demands athletic mental discipline. My director took me to the open park space to sit in the grass so that I could develop some sensory memory connections in the text.

I sat on the grass (with a blindfold on) reciting the text aloud at speed. When I lifted my eye mask at the end of the performance I saw that I had gathered an audience of park bench drunks who stood there, dumfounded, gripping their cans of cider…the substance they were using to drown that very voice. We looked at each other eye to eye in total acknowledgment.

Since then I’ve performed Not I for my nieces who were seven and 12 at the time and totally understood it. I’ve performed it for people who’ve never heard of Beckett or have never been to the theatre and yet I’ve witnessed time and time again how this deep universal poetic truth speaks directly to us and about us.

A friend of mine once said: “Beckett is a very cruel writer, it might be ok for him to describe the world in that way, but the rest of us need our delusions.”

She’s right in one sense, Beckett does get us to confront all our own truths. Truths that are so frightening to face that we run from them all the time, in fact we arrange our lives in fear of them.

Despite our paltry efforts however, we still sometimes wake with this haunting, sneaking suspicion about our own isolation, our loneliness, the scars that won’t heal, our impending death that we are all desperately fighting to keep at bay and our hilariously futile efforts to do so when it’s always just a breath away.

No matter how we dress our lives, our frailty and ourselves up, deep down we all know where we are headed and that we are all going there alone.

It isn’t easy to look down the barrel of life this way, in fact we are designed to defy this. We have an inbuilt ‘fight or flight’ system for this very reason and Beckett also celebrates this, he celebrates our defiance.

Edna O’Brien once asked me a question at a Q&A session with an audience after my performance of Not I at the international Beckett Festival in Enniskillen. “Can you tell us in one word what his work means to you?” I answered “defiance.”

But like life experiences, this work doesn’t come for free and it costs those of us who perform it a great deal.

Beckett has a way of hanging you out to dry if you don’t give him these truths plain.

He smokes out phony and fake, and makes us look ridiculous if we try to hide behind spectacle or gloss.

But in order for this to be universal it can’t become some kind of indulgent therapy for the performer either — delivering Beckett’s poetry is highly disciplined, technical work.

Walter Asmus, Beckett’s favorite director, was ruthless in this capacity. I remember during rehearsals of this current trilogy (which I’m performing at the Barbican this month) Walter wouldn’t let me get past the first six lines of Rockaby for weeks.

By the end of it I felt so hemmed in, so panel beaten. It took me right back to the frustrations at ballet school of not being allowed the luxury of a grand plie until I had perfected my demi.

I only later realised what he was doing by getting me totally technically aligned — with my tone pitch perfect, my arms outstretched to allow the breath into the voice until suddenly one day he let me go and I caught what I can only describe as an invisible current.

I felt like a glider, and I needed that momentum to take me right to end of that piece… to face the loneliest truth of all; that I am my own other… “own other living soul.”

When I looked up — Walter was weeping.

And that’s what I do when the bell goes for the first time in Footfalls (the middle play in the trilogy). With each of those footsteps I open up wounds of my own which will hum Beckett’s taut tempo.

I summon instruments that will play his score in the raw and in the real. Notes that might ostracise, notes that oppress, tickle, shame, deaden, defy.

I must, around his solid structure, wrap material of my own and here is where I must show the greatest courage and commitment. I can’t afford to scrimp.

I can’t select the off-cuts of feelings. It must be the meat itself. I must summon the very weapons that will cut it fresh.

I can’t offer up a dose of the ‘sads’… or an intellectualised memory. I can’t chicken out here and become sentimental. Beckett has shown me that sentimentality isn’t truthful — it is the language of gangsters.

Beckett has also told me that we are so much more than what we think we are, what society tells us we are, our “realities” are mostly born from fear.

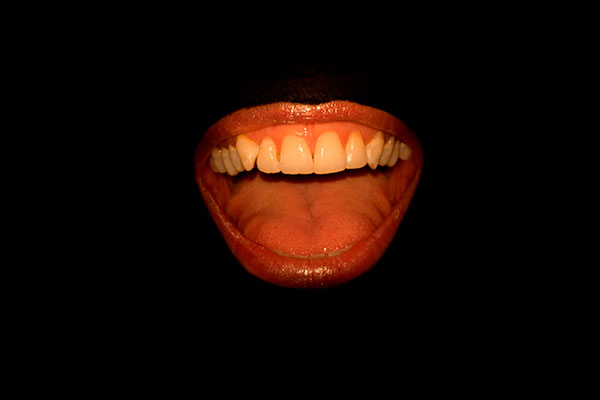

One of the gifts of the sensory deprivation in Not I is that I don’t even feel like a human being half the time up there suspended above the stage and that’s just so liberating.

I get to play a consciousness — a gazillion voices, I get to play an argument, a wound, I go from birth to 40 to 90 years old in 55 minutes. I inhabit the elements themselves — in the outside or “real” world, who’s going to want all that from me?

We tend to view ourselves and our world in bite-sized chunks, what we think we can cope with. Our idea of what a woman is, what we are… we create pithy palatable realities shaped by our small prejudices, but most of all our fears.

Beckett blows all that up and offers instead, the most enormous landscape where we must bring everything we are and could possibly be to it. No other writer I have ever come across has ever asked or offered so much.

International Beckett Season runs at Barbican Centre, Silk Street, London EC2Y 8DS until Sunday 21 June. Not I/Footfalls/Rockaby by Samuel Beckett, performed by Lisa Dwan, directed by Walter Asmus until Sunday, June 7 at The Pit, £20. For details and the full programme see www.barbican.org.uk/theatre or call the box office on 0845 120 7511