KEVIN KENNEDY’S lowest ebb came on 14 August 1998. It was a Friday.

Like any other day it had begun with a quest to find drink; alcohol to “level out”. Kennedy was fighting another crippling hangover and had only hazy memories of the night before.

There were remnants of cocaine on the kitchen table; nothing new there. The car keys, however, were gone.

As he staggered through his Manchester flat the then 36-year-old soap star realised his wife, Claire, had walked out on him. He was also late for work; late for Coronation Street. It didn’t matter. By now he had bigger concerns.

“The clock was running,” he says, “counting down to the moment when if I didn’t get that drink, everything would go wrong.”

And everything did go wrong. Or right, as it later turned out.

His quest for alcohol rapidly transgressed into blind panic. An off-licence dash saw him threaten to jump out of a moving car before necking a half-bottle of vodka in one. Arriving to work at Coronation Street inebriated, he broke down. It was a sudden and unexpected collapse.

Stunned by a feeling he couldn’t quite understand, Kennedy felt pinned to his car seat.

Coronation Street’s producer arrived to try and coerce him from the car but Kennedy felt unable to leave. Breaking down in tears in front of the soap’s producer, he was quickly signed off work and whisked off to rehab.

He thought he’d reached the end. In reality, Kennedy was at the beginning.

Fast forward 15 years and the second-generation Irish actor is in Café Rouge on London’s Tottenham Court Road. Once one of the most recognisable faces on British television, he’s sat alone, unbothered by the tourists and city centre shoppers.

It makes a change from the height of his fame when Kennedy couldn’t walk down the street without being stopped.

At one stage his Coronation Street character, Curly Watts, was so popular that he drew 22 million TV viewers for his screen wedding to Raquel Wolstenhulme, played by Sarah Lancashire.

Spotting me as I arrive, the Mancunian rips his fork out of a huge 8oz sirloin steak, holds it aloft and signals me over to his table. Greeting me with a firm handshake and some small-talk about the miserable weather, he orders me a coffee and a menu.

In between chunks of steak and talk about an impending trip to Dublin to plug the autobiography he’s here to discuss, he swigs from a glass of Coca Cola, a signifier of the changes he’s made in his life since August 1998.

Now 15 years happily sober, the 52-year-old dad-of-two is also still happily married; his second-wife Claire back by his side following that life-changing Friday. These good years, however, can’t disguise the marks of his past.

Dressed in an unfashionable, loose grey top, faded blue jeans and a yellow wax jacket, Kennedy wears more than some of the scars of his alcoholic past.

The wrinkles on his face paint him as older than his years. There are colour blotches to his skin as well; the bursts of scarlet and the broken veins all tell-tale signs of years of heavy-drinking.

Mulling over those ‘lost years’ form the basis of our 40-minute lunch. He’s quite happy to recall that time; content to mull over his past life and emphasise his recovery. Initially he found it “very painful” writing about his time as an alcoholic, but he’s getting passed that.

“When I first wrote it, I had to leave the book alone for about a month or so,” he says.

“It [the past] disturbed me and I talked to Win Parry [his rehab recovery doctor] about it and she said ‘look it’s a diseased area. You’ve not really looked at it before because the whole point of recovery is to look back’.

"Well you certainly acknowledge the past, you know. You don’t live in it. And I’ve not thought about that day in 1998 — the most traumatic day — until I’d had to sit down and write about it. It had a terrible effect, I just couldn’t think about it for a long time.”

In his book, Kennedy details an addiction that seemed to creep up on him.

From social drinks to glorious binges — the like of which the majority of us will be familiar with — Kennedy’s drinking took on a much more destructive path following the break-up of his first marriage in the early 1990s.

22 million people watched Curly Watts marry Raquel in 1995

22 million people watched Curly Watts marry Raquel in 1995Suddenly, his days started with a few shots of rum in his coffee. He would then down a bottle of vodka before heading to the Coronation Street set, where he secretly drank in his dressing room to get through filming.

Cocaine and speed were also indulged in at the height of his addiction. Some binges were so bad that Kennedy lost days of his life to blackouts and once woke up in New York, unaware he had flown there from Manchester.

“It’s fair to say that alcoholism does have that effect of creeping,” he tells me. “One minute you go from a heavy drinker into being dependant. I can’t put my finger on when or why, that doesn’t seem to interest me.

"I knew it had happened and, although I was in denial, deep down I knew that drinking in the morning was not normal. I’ve never, in fact, tried to question it. I just thank God that now I’m recovering a day at a time and I don’t have to go and live like that anymore, if I don’t want to.

"And there’s a difference. I’ve been given a choice. I could go and have a drink now if I wanted to. But I decide not to. But there was a time when I didn’t have that choice. And that’s the difference, so I try not to analyse it that much or question it every day.”

While Kennedy’s addiction and subsequent recovery forms the thrust of his autobiography, what also comes across is the actor’s deep connection to his Irish roots. His fascination with his ‘Irishness’ is as much at the heart of his life story as his fame and addiction.

Born the son of a Lancashire man and Dublin woman, Kennedy was raised in Manchester as a Catholic with his childhood baring all the hallmarks of an Irish upbringing with “the Whit Walks, first communion and confirmation and all of that”.

He tells me that he feels “spiritually Irish”. “I’m a great believer in genetic memory,” he elaborates, “and when I go to Ireland I do feel very comfortable and very at home.”

The weekend after we meet he’s excited about taking his two young daughters to Dublin for the first time and bestowing a sense of their roots upon them.

“I think that’s important, because genetically it shows them where their humour has come from,” he says.

“Where their ability to tell a story; their romanticism comes from. It’s very important that I let them know that those are the Irish genes that have produced that in them.

“My mum was born in Foley Street, bang in the centre of Dublin,” he continues, “and my father is English, although he’s the most Irish bloke I’ve ever met. He also has that ability to tell great stories.

“It was like any Irish family,” he says. “And we were regaled with tales about our Irish relatives, some of them horrific. Others were funny. So you tend to get that identity going very early.

"And later on — when I was playing bass in a showband — well, that just re-enforced a lot of what I thought about the Irish community anyway. I loved the fact that you could go out on a Saturday night and dance to a band, because that didn’t happen anywhere else.”

Music — one of his great passions — stemmed from his Irish grandmother who would play Irish rebel songs such as Dublin In The Green and The Jolly Ploughman on repeat.

“I think it was the only record she had and it was played over and over again,” Kennedy says.

“I didn’t think anything of it and I knew all the words. It was only later when I realised just how rebel it was. I just thought that it was a normal song. I’d no idea of the connotations behind it.”

His passion for music and love of Irish acts such as Thin Lizzy and Rory Gallagher was aligned, at the time, with two other Manchester kids of Irish stock.

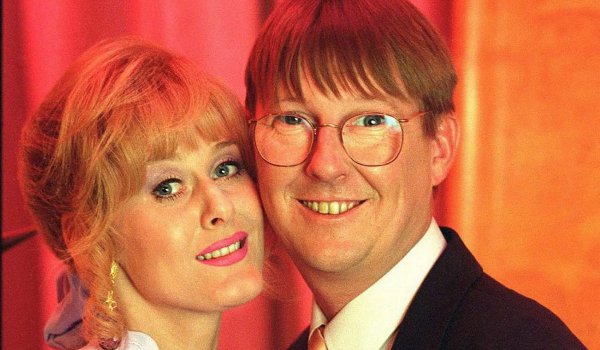

Kennedy (right) has starred in the West End production 'We Will Rock You' since 2010

Kennedy (right) has starred in the West End production 'We Will Rock You' since 2010Johnny Maher, who would later change his surname to Marr, and Andy Rourke lived a couple of streets over. Before going on to form The Smiths with Morrissey and Mike Joyce, the two 13-year-old boys formed the short-lived Paris Valentinos with Kennedy.

Marr, the son of Co. Kildare-born parents, is now regarded as the finest guitarist of his generation and remains a close friend of Kennedys. Still, Kennedy wouldn’t have changed anything to have stuck by Marr’s side.

“Johnny’s a great mate,” he smiles.

“I’ve often said it was a privilege to sit in Johnny Marr’s bedroom and watch him play because I knew then that I was seeing something extremely special and rare.

"Johnny was always unbelievable; his melodies were brilliant and I always knew he was going to make it. So I knew, that if you had to be that good, forget it.”

Joining Coronation Street in 1983, it was around this time that Kennedy began to dig deep into his roots, unearthing stories about his grandfather, a republican and member of the “old, old IRA”.

“My mum would tell stories of how my grandfather had a gang,” he says.

“Everytime you mentioned de Valera he would swear and shout ‘traitor’. So I was brought up in that kind of atmosphere, where you’ve got my grandmother playing Irish rebel songs and you’ve got granddad swearing de Valera, banging the door and shouting ‘traitor’.”

Did he notice any effect on the family during ‘The Troubles’ of the 1970s and ’80s? “I think everyone got their head down (at that time),” he says, “not so much with us because it almost had nothing to do with us — that was on the telly.

"I played in a showband at the weekends in Irish pubs and Irish clubs and there was no kind of visible hatred or... I think people with common sense knew that it had absolutely nothing to do with sensible people and it was the North — it had nothing to do with us.”

With so much Irish culture revolving about the pub Kennedy, like many, was inevitably drawn to that social hub. “Whether that’s got to do with my Irish roots, I don’t know,” he says.

“Maybe. I just enjoyed the protection that it gave you and the camaraderie of it — I enjoyed to camaraderie of being in a show, being in a band, being in a pub.

"I enjoyed the craic, the humour, most political discussions, the dodgy legal advice, the dodgy marital advice, the dodgy advice full stop. I enjoyed all those aspects of the public house.”

Dublin also, inevitably, proved a draw during his alcoholic years.

“It was Coronation Street’s little secret,” he says, “We all used to go over and have a great time. No one would bother us. They don’t judge you in Dublin and they don’t care if you’re famous. The people there are too cool.”

Close friends with Boyzone singer and actor Keith Duffy and comedian and Mrs Brown’s Boys star Brendan O’Carroll, Kennedy is easily engaged when conversation fixes on his ties to Ireland.

“Brendan’s generous with the one thing, he’s got that is most precious,” he says, “and that’s his time. I was playing in Dublin one time and my mum had a stroke. And Brendan and Keith both came to the hospital. I don’t forget things like that and I’m forever grateful. He’s got a great heart.”

Having spent 20 years on Coronation Street, Kennedy has made no secret of his desire to return to the soap he spent 20 years on. “No one would be more happier,” he says.

For now, however, he will have to contend with a central role in one of the West End’s biggest musicals. Since 2010 he’s played Pop in the Queen musical, We Will Rock You, marrying his two loves — acting and music.

Life is good.

“It’s great been back on the West End,” he says as he gets ready to dash to another press commitment.

“It’s not as mad as it was when I was drinking. I live in Brighton and as soon as the show’s over, I’m off on the train home whereas before I’d be out round the town. I’m too old for that now, I’m knackered by half past 11.

"To be honest though, life is great. I honestly couldn’t be happier and to cap things off, I’m off to Dublin this weekend. How could I complain?”

The Street to Recovery by Kevin Kennedy is published by PaperBooks