JOHNNY Jameson spent a year walking the line as Johnny Cash’s tour manager.

He remembers walking down the corridor and thinking about what he was going to say. I mean how do you introduce yourself to Johnny Cash?

He thought about growing up in Co. Meath; how he used to listen to Cash’s music on Longwave and here he was only a short walk from the dressing room door of the Man in Black.

It was 1982; it was San Antonio, Texas.

“Not too far from the Alamo, where one of my heroes got clipped – Davy Crockett," laughs Johnny Jameson behind the brim of in a black Stetson.

So he slowed step and made an acknowledgement to himself, how only months before he was touring with the Miami Showband back in Ireland, breathing new life into old ballrooms off quiet secondary roads beyond busy national routes.

Then things got quiet and the Miami said they were pulling out of town... but for Mexico?

Johnny didn’t like the sound of Mexico much but he had always liked the idea of America.

Number one he could talk and he understood how to put together a good roadshow. He loved music too and felt at home touring. Still, he’d need a lucky break once he got there.

“But even getting to know Barry Singer was a thing of chance,” he says.

Jameson is in New Jersey now, reading the classifieds in the local paper...

“And there it was; I mean I must have been there seven or eight weeks looking and this advert just appears looking for an experienced roadie... I thought ‘this is it’”.

He picked up the phone, dialled the number for Singer Entertainment, and a few hours later he was in the promoter’s home talking about Miami... in Ireland.

“Here I was in Singer’s place and he offers me a job working a George Jones concert in Elizabeth, New Jersey at the Ritz Theatre. He said: ‘If I like what I see, we’ll talk further’. Straight away I told him ‘that’s no problem’.”

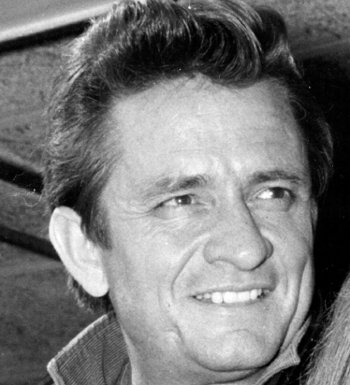

Johnny Jameson

Johnny JamesonJameson met Jones, kept up, and Singer decided the Irishman was worth keeping around.

“Three months later, I was back up out his house and he made me another offer.

"I said: ‘Johnny Cash, are you winding me up?’ He asked me could I keep this show on the road for nine months?

"Two days later, I flew down to Texas and hooked up with the Johnny Cash show... I mean, Johnny Cash, I was awestruck. I was dumbstruck.

"He was my hero when I was growing up in Ireland. He represented the outlaws and I was a bit of an outlaw. I couldn’t believe my luck.”

Back on the corridor in San Antonio, his legs were getting heavy and it wasn’t the heat of the sun, which was cooking up a serious temperature outside, that was making him anxious.

“I was thinking: ‘He couldn’t really be on the other side of this door, could he?’

“I mean there was no security, no bullshit like that.

“So I wrapped on the door, it opened and there he was... Johnny Cash. I said: “I’m your new tour manager!”

He said: “Are you from Ireland?” and I said: ‘Do we have a problem with that?’

“‘There’s no problem’ says Cash, ‘I love the Irish’.”

He remembers the first time something needed sorting. On the flight to Texas, he imagined life on the road with Johnny Cash would involve all sorts of tricky stuff, but he never figured on something simple like where the artist would eat and with whom.

So he made for the dressing room, on steadier legs this time, and asked Cash where he’d like to dine? ‘Do you want your meal here in the dressing room Sir?’

“He put his hand on my shoulder and said: ‘I eat with my men’. And he went out to the auditorium where the food was served, with the truck drivers and the riggers and the lighting technicians and was in the middle of them all.

"I often think about that, how with Johnny there was just no ego.

“Even if small things went wrong with the show he wasn’t picky about them. It didn’t matter if the food wasn’t what it said on the contract, he wouldn’t throw a tantrum for little or nothing.

"He wasn’t one of these guys that wanted M&Ms all the same colour.

“There were only a couple of things that bothered him, like he wouldn’t take the stage unless the American flag was flying and he wouldn’t tolerate a show unless the crew running it were unionised. They were his two big beefs.”

Once those things were taken care of, however, Jameson remembers the star turning in performance after performance through a period of his career where he was playing the smaller theatres in front of two and three thousand people.

“Six nights a week the hair would stand up on the back of your neck when he took to the stage,” says Jameson.

“It’s funny, no matter how often I heard it he never allowed anyone to introduce him on stage. It was always pitch black, the spotlight would come on and he’d say: ‘Hello, I’m Johnny Cash’.”

For Jameson those moments were brushstrokes of beauty that coloured life on the road bright.

Touring shows for the Man in Black was hard but enjoyable work. It was tough bringing up your family on the phone, Fed-Ex-ing a cheque to your wife every week, ringing up, hoping everything is OK.

“Then hearing some numb-nuts has run over your dog.”

There was an economic recession in America and Jameson would have to find out before he booked venues whether they were welfare towns, or not.

“Because if they were, there was no money to buy tickets the last two weeks of the month, so we had to go in the first two weeks.”

They figured these things out moving from place to place “across the Wild West in sleeper coaches”.

There were memorable nights when the music industry felt like it was moving together.

Jameson is only a few months in the job and the Johnny Cash Show is snaking its way from Houston Texas to Atlanta Georgia. It’s 3am; they’re making good time so they roll into the next truck stop.

He remembers it being quiet, despite all the rigs fixed to the diner like pins to a magnet.

They jump down off the trucks, wander in and order a fresh pot of coffee.

Jameson is looking at the specials on the board when he spots the Country singer Conway Twitty and his crew sitting in one of the booths down the far end of the counter.

He nods in the direction of Twitty’s table and they all wander down.

“The next thing, Steven Tyler and Joe Perry from Aerosmith, come through the door and we all jumped into the one booth.

“We must have been there for four hours,” says Jameson. “Talking music, telling jokes, I remember the respect for Irish music. We were talking about the Chieftains and the Dubliners, the hours just passed and next thing the sun was up, and all on pots of coffee.”

If coffee was the drug that night, then Jameson maintains he never saw Cash taking drugs any night.

“I didn’t know him when he was at that stage of his life. I worked with lots of other artists, guys like Willie Nelson and Little Richard, the Beach Boys, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes and of course things went on that shouldn’t have gone on, but the majority of the time you are on the road, life is tough for the crew and the bands. There were no orgies.”

The years passed and things started getting harder, not easier.

Life on the road was a long game and Jameson was tired of coming up short on sleep and time with his family.There were special days they all felt like one big one, like the afternoon the Navan man brought his clan down to Henderson, Tennessee to meet the extended Cash family, but by and large the relationship was professional.

“That was how I got through it. I kept it that way, done what I had to. I always made sure my work was done before I went to an after-show party.

"I mean you couldn’t be going up to Johnny Cash every five minutes like he was your brother or anything.”

But then in a way, Jameson’s role was brotherly, he was the guy who fixed things for the artists, made life run easier.

Whether that meant dining with R&B star Teddy Pendergrass when he was starring in Your Arms Are Too Short To Box With God, keeping the women away from Willie Nelson, when he could, or talking Irish roots with comedian George Carlin, he was more than happy to do it... for as long as he could.

“We all had jobs to do,” he says.

“You didn’t lick up to people or bullshit them and they respected you for that. But by the end I was getting burnt out. There were shows no longer selling out because of money problems and it was no longer fun to be on the road.

"Lots of the artists like Cash, George Jones and Willie Nelson were finding it hard to get airplay on radio because there was a big swing towards artists like Reba McEntire. It had lost its fun.”

So two decades later, Jameson left the game and made his exit, for England, cherishing the memory of all those tours, all the artists, all the friendships and those nine months in San Antonio in 1982, down by the Alamo, where it all started.

“I guess the first time I really thought about it again was the day Johnny Cash died. I was driving somewhere to get coffee and it came on the radio.

“I started thinking back to that first tour, I remember rehearsing what I was going to say and practicing how to act normal.

"I couldn’t believe that I would knock at the door, that it would open and he would be the far side of it, June Carter Cash was there with him too, and his son.

"He was walking around backstage like he was the janitor. That was him, a great artist, but just a normal working class guy.

That’s what impressed me about him most, that for all his talent as a song writer and a story teller, at the end of the day he was just a decent human being.”

Johnny Jameson lives in London and is the anchor for the Ireland’s Eye radio show on Resident 104.4 FM and a DJ working his own Angels and Outlaws roadshow.