A KITCHEN sink may sound like a strange place to fall head over heels in love with a band, but in a way it is the perfect setting for a love affair with The Smiths, who drew so much of their imagery and lyrical inspiration from the ‘kitchen sink’ dramas of the 1950s and 1960s.

I still remember the moment clearly; it was 2001 and I was in my parents’ house, washing the dishes and listening to the Very Best Of CD that I’d bought earlier that day.

The music shop that I was working in part-time had been playing this new collection on a daily basis, and I like to think that even as I went about the monotonous task of stickering CDs and answering inane customer queries, the music was subconsciously seeping into my brain.

My dad wandered through the kitchen and as dads are wont to do, mumbled something disparaging about my choice of listening material.

Suddenly, it hit me like a thunderbolt — these songs were good. They were really bloody good.

The melodies were hummable, yet also complex; the strange melancholy tone of Morrissey’s voice was at odds with lyrics like ‘Now I know how Joan of Arc felt as the flames rose to her Roman nose, and her Walkman started to melt’, and the guitar playing was second-to-none.

It didn’t take long until I was obsessively scribbling Smiths lyrics in my A4 pad instead of paying attention in school, and frantically scouring the internet for more information — archived interviews, scanned snippets from old copies of Smash Hits, rare pre-YouTube video footage — about the Mancunian quartet.

From the immaculate sleeve designs of the singles and albums to Morrissey’s unique personal style (the quiff, the hearing aid, the gladioli in his back pocket), I’d fallen hook, line and sinker.

There was no doubt about it: The Smiths were ‘my’ band. That mix of Johnny Marr’s signature guitar jangle and Morrissey’s lyrics — at once razorsharp, laugh-out-loud funny and thought-provoking — were a winning combination to my 17-year-old ears.

Morrissey performs onstage during the South By Southwest Festival

Morrissey performs onstage during the South By Southwest FestivalI had come to the band comparatively late and in a much less romantic way than most diehard devotees — a ‘Best of’ collection is hardly the ‘cool’ way to get into a band, after all.

But as my obsession grew, so did my album collection.

I immersed myself in their back catalogue, buying an album a week, allowing each one time to percolate before hungrily moving on to the next.

When I had exhausted The Smiths' discography, I continued to Morrissey’s solo output.

I turned vegetarian. I devoured the shelves of biographies written about the band.

I watched all of the films and listened to all of the bands that Morrissey mentioned in interviews, from Billy Liar to Billy Fury.

I even had a Smiths lyric tattooed around my wrist for posterity, a reminder of the all-consuming love I felt for this band and what they meant to me.

As far as I was concerned, Moz = god. It’s hard to explain your love of Morrissey to a non-believer.

He is misunderstood by many; type ‘Morrissey is…’ into Google, and auto-complete will suggest everything from ‘…a hypocrite’ to ‘…a jerk’ to ‘…a genius’.

But there is a good reason that the 25th anniversary of Morrissey’s solo career is being celebrated: he is one of music’s last true icons, attaining the level of fan worship that musicians usually only engender once they’ve popped their clogs.

Just ask the thousands of fans who voted him into second place behind David Attenborough in the BBC’s Greatest Living Icon poll in 2006, beating Paul McCartney, David Bowie, Michael Caine and Alan Bennett in the process.

He can count musicians and celebrities as diverse as Lady Gaga, Noel Gallagher, Russell Brand and Amanda Palmer amongst his biggest fans.

These are the marks of an icon. The industry has changed over the last 10 or 15 years.

The world is a different place; it’s not just the internet that has made music more disposable, but the constant whirr of the reality TV pop-star conveyor belt is more deafening and disheartening than ever before.

Yet in a sea of mass-produced pop and beige indie bands, Morrissey stands out like a beacon. He is different.

He is opinionated. He is passionate in his support of animal rights, but for someone so incredibly articulate and intelligent he is admittedly often controversial and apparently acts and speaks impulsively some of the time.

In recent years, some of his more contentious statements include describing the Chinese as a ‘sub-species’ because of their animal welfare record, and drawing parallels between the victims of the 2011 Norway massacre and the animals slaughtered for consumption at KFC and McDonald’s.

There’s no doubt about it, it can be difficult being a Morrissey fan at times, but perhaps it’s that abiding and inexplicable kinship between artist and fan that goes further than the music that rouses Morrissey fans to defend him rabidly.

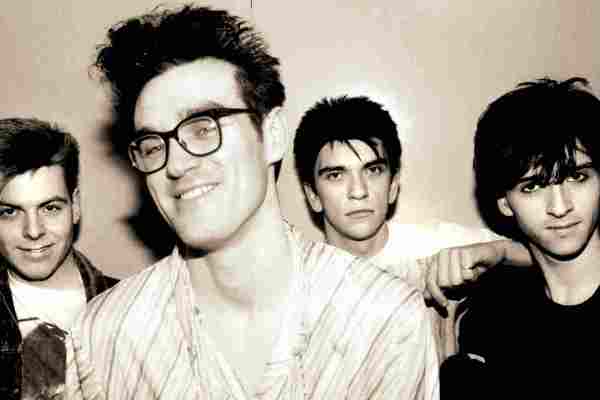

Morrissey during his days as frontman with the seminal 80s band The Smiths

Morrissey during his days as frontman with the seminal 80s band The Smiths Whether you’re a fan of his music or not, isn’t it important to have musicians like Morrissey, who air their grievances at the expense of offending people?

Aren’t popstars so safe, so sanitised, so dreadfully dull these days?

When the most controversial thing that happens during a week in the world of pop is Justin Bieber relieving himself in a mop bucket or Harry Styles getting another bad tattoo, you know things are bad.

But what about the music? By the time my fixation was fully-fledged, The Smiths had been defunct for 14 years — so seeing them live was (and thankfully remains — let’s not spoil that perfect legacy, eh?) an impossibility.

While Morrissey had embarked on a successful solo career after their 1987 split, his last release had been in 1998.

My newfound devotion was timed well, though; in 2003, he made a triumphant comeback with You Are the Quarry, returning to the stage for the first time in years.

Finally, I could experience first-hand what I’d spent hours watching on videos and DVDs, yet nothing could prepare me for the electric atmosphere of a Morrissey gig.

The pre-gig chanting was reminiscent of a football arena on FA Cup final day.

Bequiffed fans waved flowers over their heads in anticipation of his arrival, and when he took the stage at Dublin’s Ambassador Theatre, tens of people continued the longstanding tradition of attempting to fling themselves across the barrier in a bid for a handshake, a hug, some form of human contact with their idol.

It brought new meaning to the word ‘fandom’. Twenty-five years is a long time to sustain a career and fanatical support at such a high level.

Many will argue that Morrissey’s solo output is inferior to that of The Smiths, but personally, I don’t see the point in comparing the two.

The songwriting partnership that Morrissey shared with Johnny Marr will go down in musical history as one of the best; it is up there with Leiber and Stoller, Lennon and McCartney, Bacharach and David.

The Smiths were unique in that they didn’t release a bad album; arguably, there wasn’t a bad song in their canon.

Morrissey performing at Hollywood High School, Los Angeles, in March

Morrissey performing at Hollywood High School, Los Angeles, in MarchLike Johnny Marr’s post- Smiths output, the songs that Morrissey has written with other songwriters — most notably his longterm collaborator Boz Boorer — are just… different.

Their magic may not reach the dizzy heights of yesteryear, but there have been some fantastic albums over the years.

Any of the songs on 1994’s Vauxhall & I (one of the best records of the ’90s, incidentally) equal the Smiths’ back catalogue for craft and depth, while his recent work, most notably 2006’s exquisite Ringleader of the Tormentors, contains one of his finest solo songs to date in Life is a Pigsty.

What’s more, he has constantly innovated throughout his solo career, from the glam-rock of 1992’s Your Arsenal through poppier moments on the underrated Maladjusted and the swarthy rock of 2009’s Years of Refusal, taking inspiration from the places he has lived over the years: London, Los Angeles, Rome.

Morrissey hasn’t released an album since Years of Refusal, although anyone who has seen him live in recent years will have heard him play from the new batch of songs that he claims are ready to record.

They are generally striking, strong tunes, so what’s the hold-up with his tenth album?

Having been without a record deal for several years, is it that labels are apprehensive about signing such an apparently temperamental artist? Are his demands off-putting?

Does legendary status and million-selling sales records count for nothing in 2013?

And will those pesky Smiths reformation rumours ever go away?

Health problems and touring blunders over the last year or two may have stalled his progress somewhat, but despite the occasional vague allusions to retirement — and a rumoured juicy autobiography — I don’t think Morrissey is the type to simply fade into the background, á la Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond.

As an author must simply write because that is what they do, Morrissey will continue to make music, because that is what he does.

Perhaps, just perhaps, he needs us as much as we need him.

In any case, I will happily celebrate the 25th anniversary of the musician whose music defined much of my life, from that first spark as a 17-year-old doing dishes at the kitchen sink to the present day.

Like I said: it’s hard to explain.

Morrissey 25: Live from Hollywood High is in cinemas now.

[colored_box color="green"]

Morrissey’s Irish roots

‘IRISH blood, English heart’ isn’t just a throwaway line from 2004’s You Are the Quarry; Morrissey wrote the song to reflect his strong Irish heritage.

Although the young Steven Patrick was born in the Park Hospital in Davyhulme and grew up in Manchester, both of his parents, Peter Morrissey and Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Dwyer, are from Crumlin in Dublin.

In the mid-50s, they emigrated to Manchester with much of their extended respective families to start a new life, and for a period of time the young Moz was raised with both sets of aunts and uncles living within walking distance of each other in Stretford.

In a 1984 interview with Hot Press, he said: “We were quite happy to ghettoise ourselves as the Irish community in Manchester; the Irish stuck rigidly together and there’d always be a relation living two doors down, around the back or up the passage.

"It always struck me as quite odd that people who had lived 20 or 30 years in Manchester still spoke with the broadest and sharpest Pearse Street accent.”

Morrissey hasn’t shied away from his ancestry over the years, either. In the 1990s, he spent time living in Malahide, Co. Dublin and is a regular visitor to Ireland.

Earlier this year, he was spotted sipping champers at the Ireland v Austria match at the Aviva Stadium in Dublin — a strange sighting if you weren’t aware of his connection with Ireland striker Robbie Keane.

Bizarrely, it appears that the two are distant cousins through Keane’s late grandfather Thomas Nolan, who was a cousin of Morrissey’s father.

What’s more, the Keane family spent time living on Captain’s Road in Crumlin, where Morrissey’s mother Betty lived before she emigrated.

“In filial terms the Irish blood, English heart genetic between Robbie and I is evident — his chin is my chin, my chin is his,” he wrote on fan site True To You.

“He is a gentleman of the highest caliber (or, if you must, calibre), and to watch him on the pitch — pacing like a lion, as weightless as an astronaut, is pure therapy. Robbie, the pleasure, the privilege is mine.”

In response, Keane told sports website TheScore.ie that the connection came as a complete surprise, but he had returned the favour by going to see his cousin’s Los Angeles gig.

“He’s a very nice guy and I’ve got a lot of time for him,” he said. “He’s a very interesting guy and he certainly loves Ireland, I know that."

Morrissey has been vocal in his support of a number of Irish bands over the years, too.

His patronage of Dublin band Sack was so fervent that he brought the band on two support tours in the ’90s and declared that their song Laughter Lines “should be number one forever!”

His admiration for acts like Damien Dempsey has been well-publicised, while he included Irish acts Pony Club and Remma on an NME compilation called Songs to Save Your Life and signed the latter to his ATTACK! imprint.

Good lad, Moz.

[/colored_box]