THE Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed 100 years ago this month.

It was that document, signed after nearly two months of negotiations between British and Irish government representatives in London, which provided the foundation for the establishment of the Irish Free State, later to be called the Republic of Ireland.

A poignant exhibition highlighting the significance of this document and the negotiations that led to it, was launched this year to mark the anniversary.

That exhibition, a joint collaboration between the National Archives of Ireland and the Irish Embassy in London, which is titled Treaty 1921 – Records from the Archives, was first launched in London at the British Academy.

Ireland’s Culture Minister Catherine Martin was in the capital to open the exhibit on October 11, marking exactly 100 years since the start of the treaty negotiations, which began at 10 Downing Street on October 11, 1921.

Culture Minister Catherine Martin surveys the Treay ahead of its installation in the exhibition

Culture Minister Catherine Martin surveys the Treay ahead of its installation in the exhibitionThis month that exhibition moved to the Coach House Gallery in Dublin, where it opened on December 6, exactly 100 years since the signing of the historic agreement.

The exhibition, which will remain open to the public in Dublin until March 2022, is centred around the actual Anglo-Irish Treaty - which is one of the most significant historical documents held by the National Archives of Ireland.

Using that as a centrepiece, the National Archives have also released a range of other important documents from the time for public perusal - including footage and images from the negotiations in London in 1921 as well as historical records, official memos and private papers.

All have been made publicly available for the first time, which National Archive of Ireland Director Orlaith McBride claims was important if they were going to tell the tale that needed to be told in this important anniversary year.

“From our perspective we knew the story we wanted to tell in this exhibition,” Ms McBride told The Irish Post.

“We didn’t want to tell the story post-Treaty, we just wanted to talk about the journey between the truce [in the War of Independence] being signed on July 11, 2021 and the Treaty being signed at 2am on December 6, 2021.”

“So it really was that period we focused on, from our perspective, because we are not historians and we are not politicians, we are the National Archives.

“We preserve the records of the State and for the first time in 100 years we are bringing the records relating to the foundation of the State and this most important period, in terms of the establishment of what was to be the Free State and would eventually evolve into the Irish Republic, we have brought those records to the public and put them on display for the first time.”

The Treaty exhibition, which first opened in London, is now in Dublin

The Treaty exhibition, which first opened in London, is now in DublinIt wasn’t an easy exhibition to curate, Ms McBride admits, particularly as the first leg took place in London and had to be planned at a time where travel was restricted between Britain and Ireland due to Covid-19.

“Ordinarily one would use a formula that one is quite used to to set up an exhibition like this” Ms McBride explains, “but for the London exhibit the backdrop of Covid obviously made it much more challenging.”

She explained: “We couldn’t go to London, we couldn’t see the space, so we had to send colleagues from the Irish Embassy to view the space, and to measure the space for us.

“Then we actually had a call on Zoom so we could get a sense of the space,” she added.

However, the planning worked, despite the pandemic, and the impressive exhibition at the British Academy proved a hit for the two weeks that it was in place.

“The reason we chose London for the exhibition was because on October 11, 1921, 24 Irish men and women came to London to work, in some form, on the negotiations relating to a peace treaty between Ireland and the United Kingdom at the time,” Ms McBride admits.

“So, we had everyone, including the five plenipotentiaries, which are the negotiators, we also then had the secretariat, made up of officials and the secretaries, who were the force behind it in many ways, the women who were there typing memos and documents at 2am in the morning, all there in London.

“They took two houses while in London, in Hans Place and Cadogan Gardens in Knightsbridge, those were their administrative bases but also their homes for the two months.

“So, you also had those here who were running the houses - they had security, servants, cooks, etc.

“It was a hugely important task they were all charged with,” Ms McBride adds.

“But the magnitude of the moment must have been quite significant for them and what we wanted to do was to bring records to the public that would show what those two months looked like.

“So in the exhibition we have official records, government records, memos, we have drafts of the treaties we have the Treaty itself, but we also have records relating to the day to day life for the Irish delegation that was in London - the food that they bought, their expenses, the hire of cars etc.

“We wanted to really give a sense of the colour and the flavour and the full experience of all the men and women who came to London 100 years ago.”

Irish negotiator Michael Collins while in London during the talks

Irish negotiator Michael Collins while in London during the talksAs a result, the exhibition offers both political and social context to the Treaty negotiations and the Irish men and women that supported it in London.

“We wanted people to understand the context and not to see the Treaty in the abstract,” Ms McBride explains.

“We want them to not just see it as a peace treaty between two nations, but to understand that actually in 1921 you were not flying over and back between cities, getting the red-eye in the morning, going back the next evening. The Irish delegation had to come and live here.

“They were getting the mail boat over and back from Ireland to London every couple of weeks because they also were part of the government back in Ireland, so they had roles to play back there too.

“It was very important for us to communicate to people the full experience of what negotiating the Treaty entailed, it wasn’t just the meetings in Downing street, or Winston Churchill’s house, it was also what happened when they were back in Hans Place or Cadogan Gardens.”

Despite the serious task at hand for the Irish delegation while in London, the exhibition reveals that there was still time for socialising and the Irish community based in London were also keen to offer support to their visiting countrymen and women.

“They had a good time when they were here too,” Ms McBride admits.

“In many of the reports from the period that were read, there were parties, there were dinners.

“There were people like George Bernard Shaw, the Laverys, people who were well established in London society opened their doors also to the negotiators and that was important in terms of positioning them.

“There was much support from the Irish diaspora and the London Irish more generally too,” Ms McBride adds.

“Hundreds of Irish people came to Downing Street on the morning of October 11, 2021, at the start of the negotiation, and came every morning thereafter to support the plenipotentiaries in the negotiations.

“We also had this huge Irish community event held at the Royal Albert Hall at the end of October.

“It was the Irish League of Self-Determination who ran that, organised with Art O’Brien, the Sinn Féin liaison officer in London at the time.

“They knew how important it was to bring the Irish community together, to present to them the negotiators and in a way to re-establish that sense of Irishness and the sense of collective endeavour in what they were doing on behalf of Irish people back home but also Irish people in Britain.”

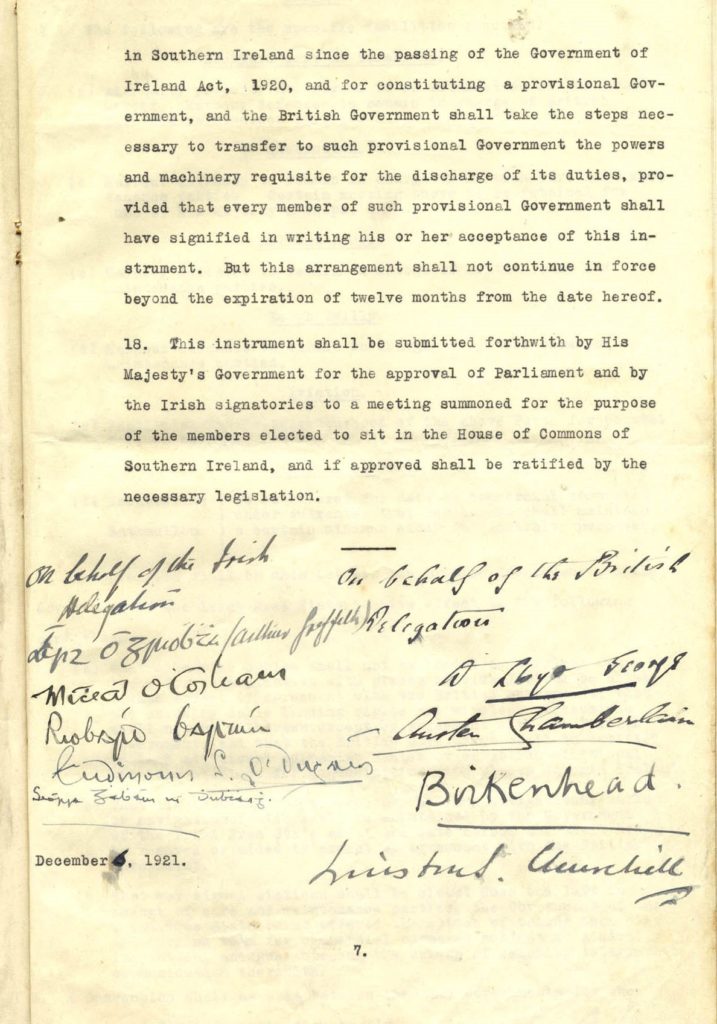

The Treaty signature part - upon which the exhibition is built around

The Treaty signature part - upon which the exhibition is built aroundMs McBride believes the support of the Irish community in Britain would have played an important role in the work of the Irish delegation during their Treaty negotiations.

“The Irish community in London bolstered them, certainly,” she says.

“I think in those moments which would have been very stressful for the negotiators, knowing that they had the support of the Irish community here in London and that there were people waving flags and cheering them on every morning when they came to Downing Street would have furthered their resolve, bolstered them at different parts in the process when the going was getting rough.

“There is no doubt that there were moments like that for them.”

Ironically, now, as Ireland reflects on 100 years since those important discussions took place, there remain pressing modern-day discussions that regard the future of Britain, Ireland and Northern Ireland in the post-Brexit world we find ourselves within.

The parallel is not lost on Ms McBride.

“There are similarities with some of the issues being faced today and parallels,” Ms McBride admits, “but from our perspective we just present the records as they are, we don’t offer any analysis, we don’t offer any interpretation, we just present the records and let people perhaps see them in the context of negotiations or discussions that are happening in 2021.”

She added: “But what I would say is, as the exhibition shows, getting into a room and having conversations, and continuing to have conversations can lead to a shared position at the end.”

The Treaty 1921: Records from the Archives is on display at the Coach House Gallery, Dublin Castle until March 27, 2022