FROM earthquake warnings to chocolate milk, here are eight brilliant Irish inventions...

1. Quick Tattoos

The first ever patent for a tattoo machine, was filed by Irish immigrant Sean O’Reilly, in New York in 1891. O’Reilly was already an established tattoo artist in the city at the time. He was responsible for the living artwork adorning some of the most well known tattooed ladies including Emma De Burgh and Annie Howard. Tattooed ladies were at the time big business, providing a popular freakshow attraction.

It’s not known if O’Reilly ever struck it rich from his patent — only one of the machines is said to still exist and there is no record of him ever opening a factory or production line creating them.

He did however continue tattooing, gaining recognition for faster and cleaner work thanks to his electronic machine. He worked out of the back of a barbershop at No. 11 Chatham Square, and occasionally the famed Stillwell Ave on Coney Island. O’Reilly died in 1908 after a fall when painting his Brooklyn home. His apprentice Charlie Wagner continued to work out of the same backroom studio until his death in 1953.

2. Chocolate Milk

Killyleagh’s most illustrious son, the Royal physician Sir Hans Sloane was a big name in the 18th century. So much so, they named Chelsea’s famous Sloane Square after him.

Sloane was born in a thatched house on Frederick Street in Killyleagh, Co, Down, not far from Killyleagh Castle. At the age of 19 he moved to London to study medicine.

A successful physician, he counted the Royal Family among his patients and grew himself a pretty substantial fortune. He become president of the Royal College of Physicians, succeeding Isaac Newton and still found the time to treat poor patients for free.

On top of all this he was by all accounts, a bit of a hoarder, it was his vast collection of books and manuscripts that became the basis of The British Library where you will find a bust of him in the entrance lobby.

It was during a collector’s trip to Jamaica when the locals introduced him to a local delicacy known as cocoa. Sloane wasn’t too keen on the drink, but found that by mixing it with milk, it became considerably more enjoyable. He brought the recipe home to London with him where it was sold in apothecaries as a medicine. Eventually a certain Mr Cadbury picked up on the recipe, and the rest is history — delicious, delicious history.

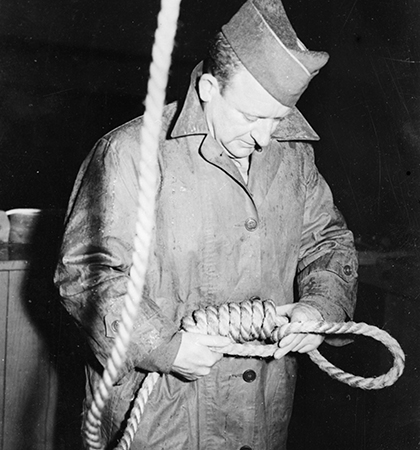

A noose being prepared, but thanks to an Irishman hanging became more humane (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

A noose being prepared, but thanks to an Irishman hanging became more humane (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)3. Humane Hanging

You should, so I’ve been told, be thankful for small mercies. If there was ever a small mercy to be very thankful for, it’s the mathematical accuracy of Samuel Haughton.

A trained doctor and an ordained priest, Haughton was Born in Carlow and worked as a professor of geology at Trinity College.

In 1896, he devised the precise mathematical equation that enabled hanging to be used as a humane method of execution. He found that, ultimately, by using the correct length of rope you could almost ensure that the human neck would snap, causing paralysis, and probably unconsciousness. This would avoid the grim spectacle of watching the convict strangling to death, which so often occurred. It’s a system that became known as the standard drop, probably most famous for being used to execute condemned Nazis after the Nuremberg Trials.

Away from the gallows he was a distinguished figure in Irish scientific circles, he submitted papers on everything from the laws of equilibrium to the motion of solid and fluid bodies. He was President of the Royal Irish Academy as well as Secretary of the Royal Scientific Society of Ireland. He was also the first of many to critique Darwin’s theory of evolution.

A dummy is used in a test-firing an ejector seat, 1958. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

A dummy is used in a test-firing an ejector seat, 1958. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)4. Ejection Seats

The ejection seat is the brainchild of James Martin born in Crossgar, Co. Down. They may seem like science fiction, but aircraft ejection seats do actually exist outside of the opening scenes of Indiana Jones movies. They play a vital role in the safety of many modern-day military aircraft. It’s a crucial mechanism designed to save the pilot’s life in the event of catastrophe, carrying them clear of the doomed aircraft and deploying a parachute.

In 1934, Martin together with Valentine Baker formed an aircraft-engineering firm. Tragically during the testing stages of their third aircraft design, Baker was killed. The plane engine seized and he was forced to make a crash landing, striking a tree stump.

Witnessing the event affected Martin so much that he became fixated on safety, in particular with the idea of providing aircraft with a means of assisted escape for pilots. After testing a number of different ideas, it became apparent that this could be best achieved via a forced ejection of the aircraft seat with its occupant still seated. This could be made to work by an explosive charge located under the seat. The idea of the ejection seat was born.

5. Boycotts

Boycotts, the withdrawal of commercial support as a form of protest, is the result of one man’s misguided feud with the Irish Land League in Irish land wars of 1800s.

The Irish Land League was a political organisation that hoped to abolish the status quo of land ownership in Ireland, whereby rich British lords extorted money from the Irish tenant farmer’s who worked the land.

Captain Charles Boycott was in charge of collecting rent from these tenant farmers on a patch of land near the Lough Mask area of Mayo. The farmers, unhappy with the cost, demanded a reduction in rent. Many refused to pay, this led to Boycott evicting a number of them.

However he couldn’t evict them all, and when Irish Land League got involved, they encouraged the farmers to band together and refuse to co-operate with him. The tactic even spread so far as local Irish-owned shops and businesses who began to refuse his custom. Soon Boycott was left with acres of land without the workforce required to harvest crops, and he couldn’t even hire a girl to do his washing.

The perceived humiliation of British establishment by Irish farmers was causing quite a stir in the British press. Eventually a relief workforce was sent to harvest the crops, and save face. They worked under the protection of soldiers from the Royal Irish Constabulary. In the end it was said to have cost the British Government around £10,000 to complete that year’s harvest.

The Irish Land League had succeeded in turning Boycott’s very name into shorthand for their new form of protest.

6. Chemistry

It’s widely accepted in scientific circles that Robert Boyle, a leading figure in 17th century academia, was the creator of chemistry as we know it. So if you hated making blue powder explode with Bunsen burners at school it’s his fault.

Born in 1627 in Waterford, Boyle was the seventh son of the Earl of Cork. He was educated at Eton, before embarking on the 17th century version of a gap year. He eventually settled in Dorset where he built himself a laboratory and started making things go bang.

He was the first to really float the idea of science as defined by a series of experiments. In fact he was the first to perform controlled experiments before documenting and publishing his procedures and findings.

His most famous discovery — that if the volume of a gas is decreased the pressure will increase — is widely known as Boyle’s law. As well as this, he introduced the litmus test to tell acids from bases and many other standard chemical tests still used today.

In 1680 he refused presidency of the Royal Society, as he felt the oath required to take the seat was incompatible with his strongly held religious beliefs.

A man clears debris from a collapsed home in Bhaktapur, Nepal where a devastating earthquake hit on April 25th (Photo by Omar Havana/Getty Images)

A man clears debris from a collapsed home in Bhaktapur, Nepal where a devastating earthquake hit on April 25th (Photo by Omar Havana/Getty Images)7. Earthquake Warnings

We have a lot to thank Irish engineers for, but Dubliner Robert Mallet’s work is still making a difference, years after his death.

Born in Dublin in 1810, the son of a factory owner, Mallet went on to study at Trinity College. He graduated in science and mathematics and joined his father’s iron foundry works.

The firm was fast becoming one of the most important engineering businesses in Ireland. They supplied iron for the railways, the swing bridge over the River Shannon at Athlone and the famous railings that surround Trinity College.

At the age of just 22, he was elected to the Royal Irish Academy. It was there he presented a paper titled On the Dynamics of Earthquakes. The paper was the first recorded use of the word seismology itself, as well as epicentre.

Through controlled experiments on a Killiney Beach, setting off underground explosions, he had managed to prove that energy moved through sand and rocks in waves. From this he could then create a series of seismic readings.

These readings are what today’s seismologists use to predict the destructive power of earthquakes, by measuring the power and energy unleashed. This knowledge can be used to arrange emergency evacuations saving countless lives.

Dr Ernest Walton at work in his Cambridge laboratory, where he and Dr Cockroft succeeded in splitting the atom, England, 1932. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Dr Ernest Walton at work in his Cambridge laboratory, where he and Dr Cockroft succeeded in splitting the atom, England, 1932. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)8. Splitting the Atom

Born in Abbeyside, Co. Waterford in 1903, the son of a Methodist minister, Ernest Walton (above) would go on to make scientific history.

As a minster’s son, he moved around the country regularly as a small boy before being sent to boarding school in Belfast. It was here his excellence in science and mathematics was first noticed. He won himself a scholarship to Dublin’s Trinity College where he continued with his studies, earning himself first a bachelor’s and then a master’s degree.

Following graduation he moved to Cambridge where he was awarded a research fellowship. It was here that he met John Cockcroft and they began to collaborate on a series of experiments, with the aim of understanding and altering the atomic structure. It was this research that resulted in what is commonly know as the splitting of the atom. The discovery would go on to win the pair the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951, and herald in the nuclear age.