EARLY hours in a north London pub after the Return to Camden festival.

It’s October 2013 and a group of musicians are winding down after a raucous set from Dónal Lunny, John Carty and Séamus Begley. On spotting Lunny chatting at the bar, someone remarks “There’s a legend in the room!”

It’s difficult to talk about Dónal Lunny without adding such labels. ‘Innovator’ is another justifiable prefix to his name. The Kildare man was a driving force behind Ireland’s seminal bands Planxty, The Bothy Band and Moving Hearts — bands which carry their own fitting labels of ‘cutting-edge’ and ‘ground-breaking’.

A composer for film, theatre and TV, Lunny is also the genius behind the Emmy Award-winning series Bringing It All Back Home and is a highly-regarded producer, having worked with Kate Bush, Paul Brady, Elvis Costello, Rod Stewart, and Clannad.

He hasn’t stopped making trail-blazing music either, recently forming exciting outfits, such as Coolfin, and teaming up with old friends in LAPD (with Liam O’Flynn, Andy Irvine, and Paddy Glackin).

This is a man with seemingly boundless energy, a sense of which one gets when chatting to him. “A lot of it is ancient history. I’ve got where I think I’m going but it could be nowhere,” he offers with good-humour and dismissive modesty.

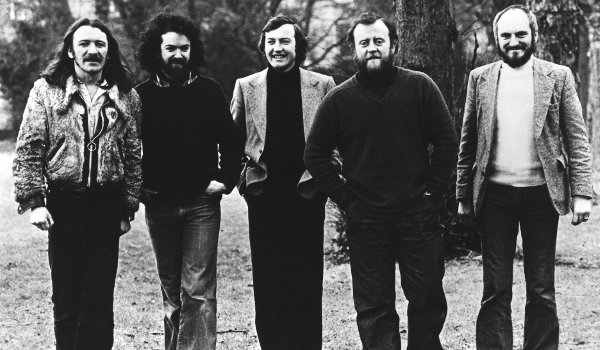

Planxty

PlanxtyLunny maintains he is an accompanist, which hugely undersells the touch that has been so influential.

“I love both songs and music but find music a bit more immediate — it’s what I do,” he says. “I’m an accompanist. I paint pictures, backgrounds, an environment in which a song or a tune lives. And I love doing that.”

A multi-instrumentalist best known for bouzouki accompaniment, Lunny is credited with introducing the instrument into Irish music (along with Alec Finn and Johnny Moynihan) — all thanks to a late-night session at Andy Irvine’s.

“Andy had a pile of various instruments from all over Europe,” he recalls. “I picked the bouzouki up and was still playing it three hours later. He said ‘Go on, take it home!’ I think I was annoying him! I put on Unison strings and that changed the nature of it really.

“A year or two later when Planxty was up and running, I went to Kent, to Peter Abnett’s workshop with Andy who was picking up a hurdy-gurdy. On impulse, I asked Peter to make me a flat-backed bouzouki and it became the Irish bouzouki.”

A musical child, he started piano aged five, lasting just a few months, preferring instead to learn by ear the classical pieces his sisters were practising and play them himself. “It really annoyed them” he laughs.

He mastered harmonica aged six, and was drummer in his first band at school, having acquired a ramshackle kit — he still “loves” playing bodhrán. But when he saw the guitars he “had to have one”. As for musical influences, jazz really grabbed the boy’s attention.

“I was listening to a lot of pop on the radio and the odd jazz piece would come up — Ella Fitzgerald or Dinah Washington or Sarah Vaughan. That was the music that really turned me on and I’d go looking for these chords.” Chords that he’s been chasing ever since which infuse his work.

Lunny’s professional career started in a very successful boy band, Emmet Spiceland, contemporaneous with The Beatles. “It was really exciting,” he says. “We sang in modulated harmonies and had hits, even with songs in the Irish language. We were big fish in the small pond of Ireland.”

It was at art college that the trad bug bit Lunny. There, he shared a bedsit with Christy Moore. “We sort of launched into the whole business of traditional songs while we lived in Newbridge,” he says.

“Later, I was working with Andy (Irvine) when Christy came back from England about 1970, and we did his second album, Prosperous”. Uilleann piper Liam O’Flynn was on the scene and when Christy came with the idea of forming a group, the connection between Christy, Liam, Andy and Donal was obvious — Planxty was born.

The first thing the band did was a tour with Donovan who was living in Ireland at the time. “He was an international star then on a par with Bob Dylan,” recalls Lunny. “We kind of upstaged Donovan on several gigs.

“There was an explosive response to Planxty as a new thing and that kicked everything off. I see a kind of parallel in The Gloaming at the moment.

"They’ve arrived with a bang on the scene and it’s lovely to see something fresh. With the ingredients they have, it’s obvious why, but there’s also a chemistry.”

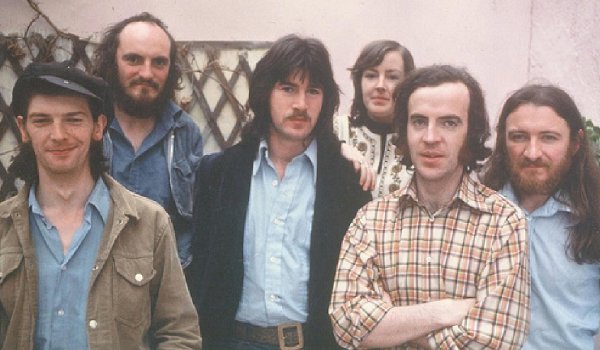

The Bothy Band was already an entity before Lunny became involved but the name came after that. “Again it was something fresh. The music had a lot of drive and passion. We ploughed a very eventful furrow for four and a half years and eventually ran out of steam.”

Planxty was reborn around 1980 and three albums followed, produced by Lunny, with Nollaig Casey (fiddler), Matt Molloy (flautist) and composer Bill Whelan (Riverdance) on board.

But Lunny’s yearning for a new sound soon sparked the formation of Moving Hearts. “I was interested in involving a rhythm section in Planxty, not just drums but something in the percussion area. A double bass might have worked but somehow intruded on the notion we had of ourselves.

“There are ethnic instruments — at least one African drum, maybe from Madagascar — a bass instrument that has a very interesting sound... I wanted to find something like that but I didn’t.

“At the same time, Christy had a bunch of songs that wouldn’t fit into Planxty so he said ‘This notion you have, could you develop it separately?’ I wanted to go for something along traditional lines but move it on to another level.

“Long story short, it became Moving Hearts and took off in another direction than I intended.”

Declan Sinnott, “a rock guitarist really, a brilliant musician” and a rock/jazz drummer joined but an important element was to combine pipes with sax, a specific idea of Lunny’s that was, like many of his notions, ahead of its time.

“It was an experiment really and it swept me off my feet! I couldn’t actually steer it more towards traditional music — that vocabulary wasn’t there.

“It’s all very well to say ‘I want this or that’ but when people look at you and say ‘what should we do?’ I couldn’t answer. All I could do was exert a bit of influence on it. And at times I didn’t want to exert an influence — I just wanted to be on board.”

It was in the closing stages of The Bothy Band that Lunny realised traditional music was where he wanted to be. When asked to compose a piece in honour of political activist Peadar O’Donnell, Lunny got the notion of putting together all the instrumental music Moving Hearts hadn’t recorded.

It became The Storm, their last album, which many, including Lunny, regard as possibly their finest. “That was a turning point for me, from when I went into the studio — a big step forward musically. The songs and arrangements we did were really good but a lot of it was orthodox rock.

“The Storm moved things into the direction of traditional music — purely a musical challenge, not political. I love traditional music and I had pinned my colours to the mast. I realised it had enough to keep me occupied for the rest of my career.”

It wasn’t that Lunny no longer wanted to experiment, but he recognised traditional music as a living culture that he wanted to promote.

“Coolfin took me along the road that Moving Hearts’ Storm started going down. Again, we weren’t coming from within the tradition. A lot of the musicians cut their musical teeth on rock.

"The challenge is to apply the feel and character of traditional music to what they were doing but I don’t have special knowledge. All I can go on is my own taste.”

Does working with singers have a different effect on him to instrumental music? “Yes. Tunes can be very evocative and touch your heart the way a song or poem does.

But songs are of a higher order in emotional and communication terms because they literally speak to you. There are great songs in the Irish tradition, monumental, tender and heart-breaking songs.

“Some are better off left naked/unaccompanied — because to bring music to them will change them for sure, and sometimes you can’t improve on what’s there. But then you could say that of traditional music.”

Lunny reveals that he went through a dilemma about the whole idea of accompaniment. “When Planxty was getting going, I asked myself really serious questions about what accompaniment did to traditional music,” he says. “I remember having not exactly a nervous breakdown but I did run into a wall mentally about it — once you touch it, you change it.

“It’s quite valid to take the tradition as it was handed down and perpetuate it like that. I maybe would have become a bouzouki virtuoso, playing tunes better than I can now. I’m not very good. But as a creative musician, that wasn’t enough for me. I preferred to be the accompanist.”

His soul-searching was triggered by the arrival of O’Flynn as “a brilliant piper. He played tunes as he’d learned them from the likes of Willie Clancy and was faithful to how they were played.

He didn’t compromise, nor would he allow us to. So it was a kind of lovely, additional discipline we had to answer to in Planxty and it reinforced our respect for the tradition.

“The logical thing is to stop accompanying, so I had to kind of acknowledge that I was going to change the nature of the tune. But, in some ways, I was doing that ‘in tune with the tune’. I love it when a tune is developed from the inside out.

The Bothy Band

The Bothy Band"It’s what I always try to do — to absorb the characters of the tune and express a parallel/counter thing. To bring in extraneous things in and impose them on top is something I don’t like.

"Some people’s approach makes me ill — with others I think ‘there’s genius’. Paul Brady has a brilliant take. He’s done lovely things with traditional music and song. He’s never abused the music.”

If the uilleann pipes gave Planxty an “untouched” purity, Lunny’s accompaniment brought out a new character in the music and some regard his vision as genius, certainly new ground.

We chat about Words and Music, Planxty’s final album, and in particular his unique treatment of the slow air Taimse Im’ Chodladh, featuring Lunny’s bold chords on synthesiser underneath O’Flynn’s pipes.

“Taimse was a really emotional session for me because Seamus Ennis (renowned singer/piper associated with the song), had died the week before. I was excited about the whole thing and at the same time kind of heartbroken. It was tough going,” he recalls.

Composing brings more freedom and satisfies a lot of musical desires for Lunny. He’s also a seemingly non-stop performer. Who’s he hanging around with these days? He frequently performs with concertina-player Pádraig Rynne and flute-player Sylvian Barou — and also Máirtín O’Connor and Zoe Conway.

Lunny has great praise for them all. They, and the likes of Andy Irvine and Paddy Glackin, joined Lunny for his St Patrick’s Day concert at Dublin’s National Concert Hall last week. He’s also put music to the RMS Titanic poem by Anthony Cronin — “one of our national treasures” — and just performed the intimate set (words, music and song) in Bray, including Lunny himself singing. He’d like to work further with Cronin. What genres is he keen to explore further?

“For years, I’ve wanted to research African music and how it’s related to Irish music,” he says with notable excitement. “I’m definitely going to go down that road,” he enthuses, encouraged by his love of complex rhythms and harmonies.

Though, he quips, he isn’t necessarily good at either. A festival of Moroccan and Irish music in Morocco is pencilled in around Halloween which he hopes will happen.

He’s been watching YouTube footage of Moroccan dancers and musicians, transfixed by the beautiful costumes and the way that elderly dancers place their feet down on the offbeat.

“I’m nervous about it,” he says. “I don’t know whether I’ll be able to springboard from there but I’m absolutely fascinated by the music.

“African percussion is obvious but I’d prefer to look at Irish songs and tunes and how elements of African music would sit into that. Not just a bloody sandwich, you know! A way for a third life form to emerge from the two.

“Pastiche is easy — sticking bass and drums on to traditional music and adding a rock beat has never worked for me. That was always the challenge in Moving Hearts — to move that sideways and come up with something that served the music directly.”

It’s exciting to hear an innovator share his fervour, still ahead of his time and blazing a trail.