WITHOUT Alan McGee’s record label, Creation, British music in the 1990s would have lacked the brio, passion and self-belief that dominated the guitar bands of the era.

Among his discoveries were Oasis, a band he stumbled on by chance and took a punt on. His lifelong pal, Bobby Gillespie, has fronted one of the most influential rock ’n’ roll acts of modern times in Primal Scream.

Famously, he managed to put out two records by famously difficult Dublin band My Bloody Valentine.

The band’s singer, guitarist, songwriter and producer is widely regarded as a sonic genius. American-born Irish musician Kevin Shields made two alternative landmark long-players with Creation but the journey, particularly with Loveless (1991) nearly bankrupted McGee.

Dealing with problem musicians seemed to be the Scot’s forte and Glasgow’s violent 1970s made him a unique and idiosyncratic presence in the corporate world of the music business.

If you are interested in the music, politics and social world of the 1990s then Alan McGee’s new biography and account of the time, Creation Stories: Riots, Raves and Running A Label is the number one book of 2013 for you.

In a quote from the book second-generation Irish musician and Oasis songwriter/guitarist Noel Gallagher describes McGee as: “A true believer in the power of music and more importantly a believer in the people that make music.

"He gave me, and many more like me a chance to change my life. A pity he supports Rangers.”

Speaking today McGee laughs off the Rangers banter. In fact he begins our conversation by revealing his Irish roots, not something your typical follower of the Ibrox club might drop into a conversation.

“From about 100 years ago my father’s side resonated from Ireland,” he says. “Believe it or not, one of the guys in The Farm (Liverpool guitar band) traces family trees. I’m going to get him to do mine. My mother’s side come from the Hebrides.”

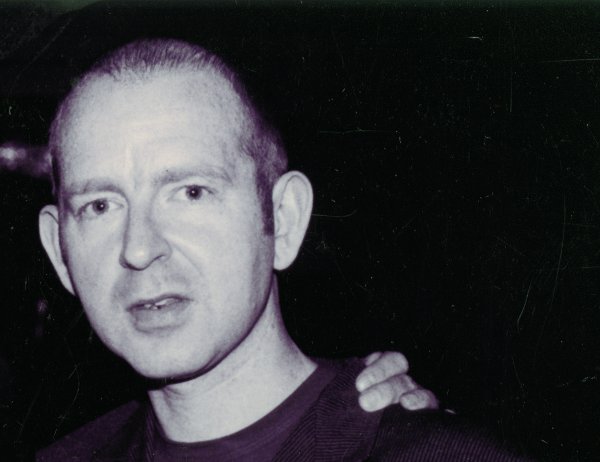

Alan McGee during his heyday in the 1990s

Alan McGee during his heyday in the 1990sIt became something of a running joke that various members of McGee’s major signings in Oasis, Primal Scream and Teenage Fanclub were Celtic fans.

“I remember Sky TV asked Noel and I to do a Celtic v Rangers game,” he says. “I turned it down. I got fed up being in Glasgow and the cabbie on the way to the airport saying ‘you’re that guy’.

"They’re not even saying to me ‘you found the biggest band in the world’, they say, ‘do you still follow Rangers?’ I live in Wales now, you know what I mean?”

Unbelievably it’s now over 20 years since McGee first discovered Oasis at King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut in his hometown of Glasgow. The band weren’t even on the bill that night but were showing enough cocky front to persuade him to have a word with the promoter and let them play a few numbers.

He describes his first impression of Liam Gallagher as looking like an “Adidas-ed up mod” and a “good looking drug dealer”. By their second number he had decided he was going to sign them.

“I thought they were a good group,” McGee tells me. “I signed lots of bands to Creation for that reason, you know, but this was the one band that I signed who became real superstars.

"You never know what’s going to happen; anyone that says they knew, well that’s just bullshit, they’re lying.

“I don’t think we knew they would be that big; I thought maybe they would get a gold album (laughing). I just signed them because of the connection that I felt. That was Creation. I’m still like that. If I believe, then I believe.”

What becomes apparent in the book was the sense of hostility directed towards Oasis from the music industry.

London-centric journalists — and even employees at Creation records — didn’t like the band’s working-class swagger and felt that their image and music was yesterday’s papers.

However, within three years of signing, Oasis had become a cultural phenomenon selling millions of records and playing to vast sell-out crowds across the length and breadth of the country.

McGee takes great pleasure in proving everyone wrong and at times comes across as a wild-eyed father figure willing his young to take on the world. Undoubtedly Oasis produced their most vital work during that period.

Creation Records were behind classics such as Oasis' Definitely Maybe...

Creation Records were behind classics such as Oasis' Definitely Maybe...By the time they released Be Here Now (1997), a record which proved to be something of a disappointment, both the Gallagher brothers and McGee had achieved their most outlandish dreams.

When he eventually dissolved Creation in 1999, Liam Gallagher was left feeling vulnerable. In a sense he had been under McGee’s wing since the tender age of 21.

“There was quite a gap in our ages and perhaps he found it helpful to have me around as a sort of father figure,” McGee muses. Likewise his employees took it badly. Again McGee underlines his point.

“I hadn’t meant to hurt anyone and I’m sorry if I did,” he says of his decision to dissolve the label. “But I never promised to be their dad.”

The former Creation records boss — like the Gallagher brothers — had himself suffered at the hands of a violent father.

McGee plays it down but the book does reveal some shocking moments. In a roundabout way he attributes his sense of drive and ambition to that time.

“I dealt with all of that years ago,” he says of his imperfect upbringing.

“You can’t make too big a deal of it. Of course I could have milked it by saying this or that happened, but the reason I never did was that I don’t think my story is very different to any 53-year-old bloke from Scotland growing up in the 1970s.

"Maybe it spilled over a couple of times into going to hospital (starts laughing) but society has changed a lot since then.

"That violence that happened in the family, that was acceptable in the 1970s, so it looks really bad in 2013 but it was socially acceptable then and that’s the truth.”

It’s true that McGee’s Creation Stories evokes a more violent culture.

“Yeah it was. It wasn’t so much gangs for me, I was never into that, but it was just a violent time. I’ve got a 13-year-old kid, today bullying is immediately reported. In my time there were people putting bricks through the staff room window.

"The teachers were on a break having a cup of tea, you know what I mean. We are completely culturally different now. Today that behaviour is completely socially unacceptable. At that time nobody thought anything of it.”

Those gritty times weren’t all dark shades. He formed the most significant friendship of his life with his oldest comrade in Bobby Gillespie.

The singer’s family home became something of a refuge for Alan when things got out of hand.

and Fuzzy Logic by Super Furry Animals

and Fuzzy Logic by Super Furry Animals“Bobby’s family were pretty far ahead of their time; the only parents I knew who didn’t batter their kids. He’s my oldest friend. I’ve known the guy for 41 years. We’re probably stuck with each other until we pop off, you know what I mean.”

As well as signing some of rock ’n’ roll’s most difficult acts, the Glaswegian also managed them.

In 1984 he secured the signatures of the notorious Reid brothers, taking them on also as manager after Bobby Gillespie handed him a tape of their band, The Jesus And Mary Chain.

The band quickly made national headlines and became indie and alternative darlings, yet McGee was left depleted when the band fired him.

The experience was vital and gave him a taste for success, along with an even greater confidence, and ultimately good training, for Noel and Liam Gallagher.

Around the same time Bobby Gillespie left the East Kilbride band to concentrate on Primal Scream. While McGee admits to not really getting the band until years later, he remained fiercely loyal to his old pal and it paid off.

“I don’t think they ever made sense to me until Screamadelica (1991) if I was being honest,” McGee says. “People used to say that me and Bobby had a cynical plan about figuring out how to be successful in the music industry (laughs).

We never had a conversation in our lives about the music business in that way. It was based on complete faith that we were doing the right thing at the right time. It was all intuition.

“I just put records out, but Bobby is the most important person we ever worked with because he had a political outlook as much as a musical one and that was really vital. He’s the most important person we signed on that level in terms of shaping the culture.

"They were also our flagship band. People signed to Creation because Primal Scream were on the label. Oasis signed with us because we had Bobby, you know.

"Now music is a middle-class sport, you have to have a rich dad to go into music now to be honest. If you look at a band like The Horrors, their dads are psychoanalysts and psychiatrists.”

Bobby Gillespie of Primal Scream has been a friend of McGee's since they were kids growing up in Glasgow

Bobby Gillespie of Primal Scream has been a friend of McGee's since they were kids growing up in GlasgowIn the autobiography McGee is frank about a breakdown he had just as Oasis were on the rise; the rock ’n’ roll lifestyle and difficult personalities were perhaps taking their toll, particularly working with a “perfectionist genius” in My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields.

McGee suggests My Bloody Valentine, who formed in Dublin, could have been the most influential band he signed but today he plays down the complexities.

“Too much has been made of that, I’m very proud of putting out Loveless, as you would be, it’s an amazing record. This year I think what Kevin Shields done on his new record, MBV, is a total anarchistic statement.

"He circumvented the major record companies, publishing companies, the distributers and did it all from his own website. It’s pretty incredible what he did. He’s a brilliant musician but what he did as an idea is amazing.

"You’ve got to respect him, you know. I think he’s a visionary, the records are out there and you are either into them or you’re not. What Kevin did with the records he made was brutally fantastic.”

After handling the likes of Liam Gallagher, Kevin Shields and Bobby Gillespie throughout the 1990s, Alan was nominated to manage perhaps the most troublesome act of them all in The Libertines.

"Although he was reluctant at first, he took on the challenge with relish. His stories of managing the band are easily the most disturbing in the book. When I ask him ‘who was the toughest personality to organise’, without flinching he answers: “Pete Doherty, (long laugh).

“I think he’s an incredible talent,” McGee says. “It was sad because I couldn’t get to him and I couldn’t pull him into line; if we had managed to straighten them (The Libertines) out at that point in time they were going to become the biggest group in the world.”

Certainly McGee believes the band are still capable and young enough to claim the prize to have another go. As well as Pete Doherty he remains a major champion of Glasvegas.

“I love them, when was the last time a platinum band broke of Parkhead in Glasgow? It was amazing and James Allan is a superstar; the only person who holds James back is James but musically the guy is a major talent.”

The good news is that McGee is back and looking for bands. After a period of disinterest and latterly ill health, he’s now fully recovered.

“I got ill earlier this year. My immune system had fallen to bits so I went to see a doctor in Harley Street and he recommended this new drug on the market. After that I finished the book, started a new label and lost 34 pounds in weight, it’s been mental!”

Earlier this year McGee announced his long-awaited return to the music industry with 359 Records, a company he runs from Wales having moved permanently to Hay-on-Wye after growing tired of London life.

2013 has been a good year for the mogul who now also deals in property and took on his first acting role in the excellent music business comedy drama Svengali.

“It got pretty good reviews, I was just playing myself which is why I’m good in it,” he says. “The reason it works is because the guy got me not to act.”

So what’s next for Alan McGee?

Without doubt he still has the desire to find the next big thing. Many of today’s biggest rock ’n’ roll acts seem dull in comparison to when the Glaswegian was Kingmaker and dream-weaver.

Today it sounds like he might be up for one last shot at the title. “Yeah, I’m still up for the cop. I don’t know what’s next but I’m just enjoying it all now.”

Creation Stories: Riots, Raves and Running a Label is published by Sidgwick and Jackson priced £18.99