MY WORK WITH the poorest of the poor takes me into some of the worst areas of Saigon, or Ho Chi Minh City as it is now officially called.

It was there I first came across Phuc and his family, down by the railway tracks in Nhieu Loc, the city’s canal district, a place more squalid than any shanty town, where people live in constructions like cages, one on top of the other.

In the midst of the congestion I noticed something that looked like a small coal box — just a few boards of broken wood nailed together.

I pulled back the curtain, peering into the blackness, and I was hit by the foul stench of human flesh. A family of five were hunched inside: a father and mother, two little girls and a young boy of about 10.

The box was no more than four feet square, smaller than many Western toilets. So small, in fact, that there was no room to lie down — the family had to sleep sitting up against the walls.

My eyes went to the boy because, unlike the others, he was not sitting but lying on his back, motionless, with his matchstick legs drawn up towards his chest.

A closer look told me he had cerebral palsy. Tears sprang to my eyes and I wanted to be sick, but I knew I mustn’t, it would only add to the humiliation these people were already feeling.

I was with my Vietnamese colleague Helen Thuong. “Helen,” I said, “please ask the father if I can speak with him.”

The father came outside. He was about 35, very neglected-looking and thin. The mother and children looked neglected and worn too, but the father looked worse.

I was struck by the pain in his eyes and the lack of hope in his voice when he spoke to me — his low self-esteem.

My first reaction was to do something immediately, to take them out of this hovel, this box, but I knew it was impossible.

“Could you come to the Children’s Centre?” I asked him through Helen. “I think we might be able to help you.”

He looked somewhat taken aback but with great dignity he nodded and said yes. I asked him if I could see the whole family.

Very politely they came outside. The two little girls, ragged but beautiful, stood looking at me, mystified by this yellow-haired stranger who was talking to their father.

The father carried the little boy out, and I was immediately struck by the tender way he lifted and held him. I could see that he often did this by the way the boy’s arms automatically went around his father’s shoulders.

The little boy’s name was Phuc. I saw the back of Phuc’s head. It was not rounded, as it should have been but almost flat.

Phuc had spent all of his short life lying on the ground. His body was twisted from head to foot and as frail as a five-year-old’s.

Phuc’s parents came to my office at the Foundation that afternoon. I could feel their embarrassment.

The Vietnamese are a gentle people, but they are very proud and this family was obviously the victims of circumstance.

I explained that I too had been very poor when I was a child. I had lived in terrible conditions with my own brothers and sisters.

“Please don’t be embarrassed,” I said, “just tell me how can I help you. What do you need most?”

I felt almost silly asking. I could see that this family needed everything.

The father said, “I need a job…If I had a Honda-om [a taxi], I could be a Honda-om driver,” but he shrugged as he answered, as if it was an impossible idea.

“Let’s talk tomorrow,” I said. Next morning at 8.30am, we started the brainstorming.

We agreed that Phuc’s father’s idea of getting a Honda-om was a good one and I asked Quoc, our minibus driver, to find a second-hand one in good condition.

We all agreed that housing was a priority, and that for the sake of their health, we had to act fast. No decent person could leave them living in those conditions. But could we afford to rent them a big room, putting down at least one year’s rent in advance? I looked across at Mr Hai, our accountant, a man always in control, never fazed.

“Well,” said Mr Hai, “you always say to us, if we don’t have it, we must find it.”

“I love you, Mr Hai,” I said, “because you always give me good answers.”

At half past 10, little Phuc and his family arrived. We told the parents about our meeting and asked them what they thought.

It was difficult for them to take in what we were saying. "We would like to arrange for Phuc to go to our Physiotherapy Unit in Phuang District for an assessment,” I said.

“If he goes, Dr Loc there will take good care of him.”

In Vietnam, there is neither the knowledge nor the equipment to care for children with cerebral palsy, but I was hoping that Dr Loc might be able to suggest some kind of long-term rehabilitative programme.

They also agreed that they and the little girls would have a medical check-up at our health clinic. But when I offered to look after Phuc full-time at the clinic until I could find them a room, they both shook their heads.

It would be for only a matter of weeks, I explained, until we could find them other accommodation, and in the meantime we would give Phuc proper nourishing food.

The answer was still no; Phuc was their son and they wanted to take care of him themselves.

When we gave the Honda to Phuc’s father he just stared at it. I gave him the papers and suddenly his face broke into a huge smile.

We found a piece of land just outside the city. It was cheap, about e2,000 with a little green field around it, which we would be able to buy for the family, thanks to a generous anonymous sponsor.

We invited them all to come out in the van with us to see it and give us their opinion. There was a tremendous sense of excitement. The van left the city behind and we turned off the main road into a country land.

We stopped and parked. The children pressed their faces against the window, staring out.

I wondered what they were thinking. I handed Phuc to his father, and the little girls and I held hands and skipped through the grass to the little plot of land.

Their parents followed with Phuc, and while they were talking to Helen, I took him in my arms again.

He was moving his head from side to side, squinting up at the vast blue sky, gazing up at the great arc of blue, utterly transfixed.

He had never seen such space or light before. I laid him gently down and guided his hands over the grass. Phuc was pulling at the grass, holding it, his fingers exploring with incredible intensity.

His head, his eyes and his whole face were moving. It was as if, after 10 years of lying in the dark like a corpse, Phuc had come to life. The family liked the plot. With help from volunteers they built their home within a month and moved into it.

Phuc’s mother takes great pride in the little business she now runs, selling her home-grown flowers from a roadside stall.

His father goes into the city each morning to work with his blue Honda-om, and when he has some spare time he helps us at the Foundation.

Physiotherapy and a good diet have done a lot to ease Phuc’s condition.

Last time I saw him at the Foundation he was in a snazzy new wheelchair and he was wearing a baseball cap just like any other cheeky 10-year-old.

He and his sisters have the chance to be children now.

So I’d say my philosophy isn’t just about mending bodies.

It’s about restoring people’s independence, giving them a life, not just an existence.

It’s about respect and love and dignity. Those are the things we owe our children.

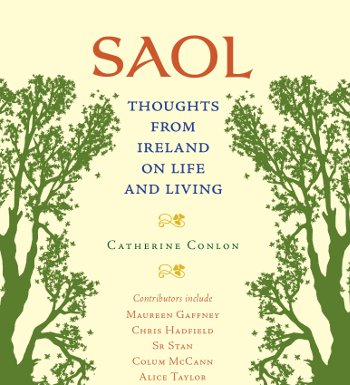

This extract is adapted from Mama Tina (1999, Corgi) in Saol: Thoughts from Ireland on Life and Living by Catherine Conlon, published by The Collins Press, price £11.99.