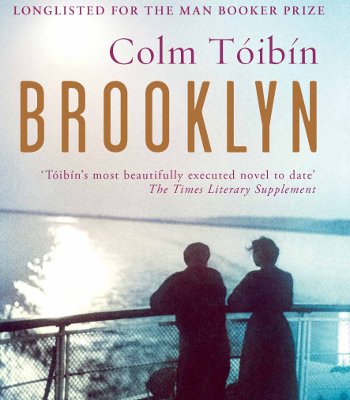

“NO WORK for anyone, no matter what their qualifications,” is the bald reality facing Eilis Lacey in Colm Tóibín’s celebrated novel Brooklyn, a condition that Irish emigrants everywhere know well.

After the announcement last year that the movie of the book is being made by John Crowley, the latest news is that filming begins in Tóibín’s native Enniscorthy this week.

Brooklyn won Tóibín the 2009 Costa Novel Award and, though the story is set in 1950s Wexford, its relevance holds for our current times.

The heroine Eilis is forced by circumstance to take the steamer ship from Liverpool to New York, joining the line of huddled masses that preceded her and, narratively at least, embodying the physical and emotional wrench that today’s migrants also feel.

“Parts of Brooklyn are full of Irish,” Eilis is told, a true-enough statement for the last 200 years.

Saoirse Ronan is slated to play Eilis (replacing the earlier choice of Rooney Mara), while the unstoppable rise of Domhnall Gleeson continues as he plays Jim Farrell, the man who complicates Eilis’ romantic life.

Readers of the novel will recall that Tóibín cleverly interweaves a kind of double-whammy in rendering the emigrant’s dilemma and that Eilis finds herself exiled not only once, but twice. It’s a tenderly-spun emotional portrait that relies on Tóibín’s gossamer-like narration and translating it from page to screen is tricky.

Therefore Crowley is the right choice to direct the adaptation.

Crowley has proved himself adept at conveying stories in which everyday people deal with burdens that are sometimes extraordinary and sometimes mundane, but always personally important.

More prevalent in theatre than cinema, he has nevertheless won acclaim for social-realist pictures with a comic twist, like Intermission (2003) and Is Anybody There? (2008), and also for the Bafta-winning Boy A (2007).

If last year’s action movie Closed Circuit was an uncharacteristic misstep, then Brooklyn should restore Crowley’s footing.

But this production offers the chance to ponder again that old debate of how ‘the book’ compares to ‘the film’, and the relative merits of stories conveyed in both mediums, a talking point since the earliest days of cinema.

Early cinema, being a fledgling story form, relied heavily on filmed adaptations of classic novels or plays (Shakespeare was a favourite) and tensions still exist between advocates of page or screen. Literature lovers think cinema devalues intellectual narrative, a stance that movie viewers see as pretentious and snobbish.

Certainly, more often than not, readers who’ve enjoyed a good book feel disappointed by the film. An illustrative example is Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, which has been adapted for the screen four times but without the aesthetic quality of the visuals ever matching the prose (though Baz Luhrmann’s effort is the most eye-catching yet).

Part of the difficulty of adaptation turns on the different natural narrative devices of page and screen.

The writer can generate with mere words rich and vivid imagery for the reader’s mind’s eye, but the director must do the same for the viewer with “real” materials, or at least with props that look similar enough to be convincing.

For film-makers, having to “show” rather than “tell” is a real headache. A classic case relates to John Huston’s filming of Joyce’s The Dead (1987), which is set during a gathering of sophisticated Dubliners who take their seats around a fancy dining table for a lavish dinner.

Part of the diners’ feast includes a roasted goose, simply conceived with a stroke of the pen for Joyce but for Huston’s production it was necessary to buy an actual goose and actually get it cooked. Imagery can be telling, for novels but, for movies, seeing is believing.

Similar to others before him, Crowley has no simple task in honouring the writing in Tóibín’s Brooklyn and matching it with his own vision.

Brooklyn will be released in 2015