STROLLING through London’s West End in recent weeks you might have been forgiven for thinking that you’d stumbled upon an Irish stronghold in the centre of the capital.

On Charing Cross Road alone, Irish names dominate the multitude of theatre placards and posters.

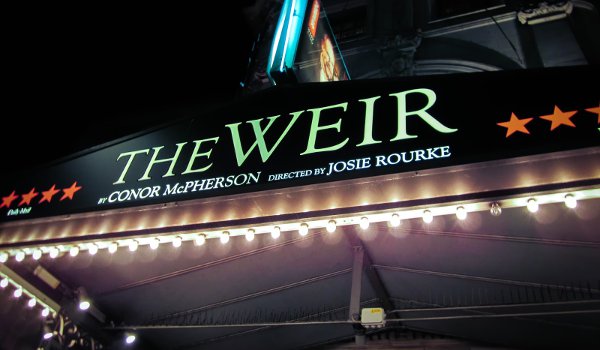

You’ll see the names of Conor McPherson, Ardal O’Hanlon, Dervla Kirwan and Risteárd Cooper dotted all over Wyndham’s Theatre in support of The Weir. A few metres away Roddy Doyle’s name is up in lights high outside The Palace Theatre, while across the road Enda Walsh’s name sparkles across posters for Dublin-set musical Once.

There are more too. Graham Linehan’s The Ladykillers continues to delight on The Strand, while you might have seen Samuel Beckett’s name return to the West End last month as Westmeath actress Lisa Dwan revived three of his plays at the Duchess.

Add to that, a recent well-received run of Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan, with a predominantly Irish cast, and it’s fair to say the West End bleeds green.

Such strong, surface-level, dominance of Irish talent on one of the world’s leading theatre stages is buoyed by a wealth of talent behind the curtain.

Meander in and out of any of London’s 40 odd major West End theatre venues and you’ll hear Irish accents in the ether; see Irish surnames pop up in programme notes.

And it’s not just London either.

From Liverpool to Sheffield to Lands’ End, Irish theatrical talent is thriving in Britain.

So what should we read into this? What does such an influx of talent say about Ireland’s theatrical tradition and its reputation for cultivating great creative people?

Can parallels with the ‘brain drain’, so prevalent in the country’s export of nurses and teachers, be drawn with its acting and stage talent?

Could Irish people’s success over here be linked to a wider decline in theatre back home or is it simply a fact that great talent will always be drawn to the bigger stage; that the best players always want to play at the top level?

Conor McPherson is a man well-placed to ponder such a question. Touted as Ireland’s greatest living playwright — and certainly the finest of his generation — McPherson got his break in London (and not Dublin) at the age of 24, after the Bush Theatre ran This Lime Tree Bower in 1995.

The Weir soon followed and debuted in London in 1997. Ever since, McPherson has tended to debut work in London, developing relationships here, away from the country of his birth.

“I just couldn’t get my plays on in Ireland — I couldn’t make a living,” he says.

“London is an hour away on a plane and there’s loads of theatres, so it’s a no-brainer. Once that started to happen, you end up in relationships with theatres and people that you’re working with, and friendships and stuff, so you just continue along those lines. So that was just very organic.

Conor McPherson

Conor McPherson“I was just trying to keep going and make a living as a writer. You go where the love is. It’s the same for anybody with anything so there was no conscious thing like, ‘I don’t like Ireland’ or whatever. It wasn’t like that at all.

"I was continuing to live in Ireland, then travel and do my work. Then eventually the plays did get put on in Dublin and that, but that’s just how it was. There was no principle involved.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Cathal Cleary, a 32-year-old director from Roscommon who is a leading light in the wave of Irish theatrical talent that has come after McPherson.

Cleary’s big breakthrough came in 2011, nearly three years after moving to south London, after he won the JMK Trust Directors Award and subsequently spearheaded a revival of Enda Walsh’s Disco Pigs at the Young Vic. His 2008 move to Britain was, he says, “the only other option”.

“Theatre was still not at a full, professional level,” Cleary explains of his initial years in Ireland where he studied in Galway and formed the Zelig theatre company. “I wanted to get my teeth into some fresh, new theatre and learn from the best. That wasn’t happening in Ireland. I was trying to contact the Abbey [in Dublin] and there was no word.”

Like McPherson, Cleary had hoped that Ireland would have supported his ambitions; that the country’s most well-known theatres, The Gate and The Abbey, would have staged his work and nurtured his talent.

“I would have been up for, in theory, the possibility of working in some of the bigger companies like Druid and the Abbey,” says Cleary, “who I admire greatly.

"Ireland is such a small population; the theatre-going audience is quite small. The companies that survive or make work — you can count them on one hand. The opportunities are very, very limited.”

Those opportunities begin to shrink even further when one considers how little new work is being produced on the Irish stage and the quality of the work that does make it in front of a paying audience.

Last month, an independent report co-commissioned by the Arts Council and Dublin’s world-renowned Abbey Theatre was published in a national newspaper. The report suggested that, based on a dozen productions at the theatre since May 2012, the Dublin venue was falling short of its boast of being a ‘world-class theatre’.

The famed playhouse, which, it probably should be noted, staged only three new works on its main stage in 2013, was last month awarded €6.5million in State funding through the Arts Council for the year ahead.

This figure represents almost two thirds of the total €10.2million dished out to nine of Ireland’s major theatres, which are awarded regular funding under the banner of “key arts organisations”. Dublin’s other major theatre, The Gate, is one of these beneficiaries, receiving €908,000 this year.

Although The Gate receives significantly less funding than the Abbey, the theatre has drawn considerable criticism over the past decade for its lack of investment in new work. In 2000 and 2001, the Gate housed 13 productions. A quarter of these were new works, with one of those four productions a trio of shorts from Conor McPherson, Neil Jordan and Brian Friel.

More than a decade later that small amount of new work has dwindled. Over 2012 and 2013, only one of its 13 productions was a non-classic work written in the last 25 years (The Last Summer by Declan Hughes, 2012).

The Irish Post contacted the Gate Theatre’s Artistic Director Michael Colgan numerous times to try and ascertain why the theatre appeared to be reluctant to put on more original works but our calls were not returned.

Irish playwright Colin Teevan says that the Abbey’s falling status and the lack of new plays at The Gate points to a “real problem in Irish theatre”.

“I don’t think the Gate’s been doing anything new for 20 years,” he says. “They’ve got a formula and they stick with it.”

Teevan has turned his creative attention full tilt to London since moving to the city in 2002. The playwright, who was recently awarded a BBC radio drama award and has penned RTÉ’s upcoming drama on former Taoiseach Charles Haughey, Citizen Charlie, says he hasn’t had a play produced in Ireland for 20 years.

“I had conversations with the Abbey about three or four years ago,” the 45-year-old Dubliner says. “I’m not quite sure what happened with them — they seem to have ceased production all together.”

Both the Abbey and the Gate will say dwindling audience demographics are at the root of their problems. Young people just aren’t going to the theatre in their droves and this is something Teevan, who wrote The Kingdom for Soho Theatre in 2012 and has had major projects at Britain’s National Theatre, acknowledges.

“When I went to the Abbey I was really shocked, as the whole audience was grey-haired and entirely white. It hasn’t attracted any of the new immigrants; there certainly wasn’t any Polish-speaking.”

This contrasts, Teevan says, with the “cultural fertilisation” offered in London’s theatre scene which fosters and promotes new and exciting work. “I go to the Young Vic,” says Teevan, “and it’s a really young, excited audience.”

Director Jamie Lloyd and author Roddy Doyle

Director Jamie Lloyd and author Roddy DoyleThe Young Vic sits in the heart of a small stretch called The Cut in the Southwark area of London and has a history of promoting new plays. A stone’s throw from Waterloo, it is a home-from-home for all things theatre outside the West End.

Head east from the Young Vic and you’ll pass trendy pubs and off-beat performance spaces frequented by amateur groups, before reaching Jerwood Space, a rehearsal studio for major international shows.

Or, head west and you’ll pass the National Theatre Studio, an engine room for actors, composers and writers to hone their crafts for the big stage. Nearby is the Old Vic, from which its younger counterpart was originally an off-shoot.

Cathal Cleary got his break at The Young Vic after being accepted on a director’s programme and fondly remembers the time as an “incredibly productive and exciting” period.

“It was the one building that has a very, very open door policy to young directors,” he says. “There’s a lack of judgement at the Young Vic. They are interested in whatever background you have, whatever experience you have — as long as you’re professional and hard-working.”

It isn’t just at the professional level that the Irish are making an impact in such theatres.

Back on the Cut, the Old Vic’s rehearsal studio is holding auditions for a contemporary and community-led play called Housed.

Wexford actress Rebecca Hadrill is one of dozens of Irish voices who have been heard among the near-1,000 people who’ve auditioned over the last five days.

She left Ireland more than two years ago in search of the elusive break.

“It was the right time for me to leave,” she says. “There’s lots more opportunity in London for auditions, training and to make contacts. There is so much great new theatre on every night of the week, so I get to learn from observing too.”

The actress, two weeks previous, performed in a site-specific performance of John Millington Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World across town at the Corrib Rest pub near Kilburn, North West London.

The performance was put on by the Acting Gymnasium — a troupe formed of a strong Irish contingent who make use of Camden’s Irish Centre for bi-weekly rehearsals.

Antrim actress Kathryn McCartin was lead in the production and the 26-year-old, who moved to London last year, says the main benefit between pursuing her career in England as opposed to Ireland is that she has more of a chance to learn.

“There’s a marked difference in scale moving from a small pond, within a self-contained industry, where everybody knows everybody, to the theatre capital of the world,” she says. “I think there is more of a culture of ‘learning on the job’ in Ireland.”

Cathal Cleary

Cathal ClearyThe girls’ stories echo the view of David Grindrod, the respected casting director involved in both the Once and The Commitments musicals.

He says there is a lack of good training for actors in Ireland and that this is problematic. “We need better schools over there,” he says. “Sometimes they [actors] lack the training so they have to come to England.”

Even for those who do get the right education, the right training, Ireland’s theatrical problems still always turn back around to the lack of opportunities for talent to thrive, says filmmaker and acting coach Terry McMahon.

“We haven’t had the courage to go where France and England have, in terms of drama,” says McMahon.

“We have a bunch of young people in Ireland right now who could be extraordinary if they are given the chance. I teach acting to all ages and all experiences, I have taught hundreds of actors. I have seen talent that would blow your mind, but the opportunities just don’t seem to be available to them.”

Teevan too sees no lack of Irish talent. Combining his work as a writer with his role as a professor of playwriting and screenwriting at London’s Birkbeck University, London, he estimates that between 10 and 20 per cent of his students are of an Irish background, adding that “some of our very best writers on the courses are Irish”.

Opportunity though is the key point. Stay in Ireland and their work may never see an audience; go to Britain, however, and the chances of serious success multiply.

“There’s a huge difference between writers who come over and live here and the writers whose works come over,” Teevan says as a means to emphasise his point. “There’s not many of the latter.”

While the lack of opportunities in Irish theatre have fuelled an exodus to London and further afield, those creative talents who have remained in Ireland have turned their endeavours to theatre’s greatest audience competitor — film and TV.

You need only look at Ireland’s most popular drama of recent years, Love/Hate, which stars a number of actors who have made their name on the show. Like the acting talent, the show’s creator and writer, Stuart Carolan, began writing for the theatre but found greater opportunity for his talent away from the stage.

Edwina Kelly, an established make-up artist from Kilkenny, has worked across numerous platforms over the last 15 years and is well-placed to see how the creative sands have shifted.

“The last few years has definitely seen a focus on TV and film,” she says, adding that while she felt the theatre scene in Dublin was strong, she’d only done “the odd theatre gig” recently.

“In film, you can get booked for weeks or months and the properly-funded films are quite well paid,” the 35-year-old says. “I get about one theatre gig a year. There’s not as much work in theatre for make-up artists, mainly because, as most productions are in smaller theatres, they cannot normally afford to pay a make-up artist for every show.

"The bigger stage performances would have hair/make-up/costume in for every show; and Dublin has a few people that tend to get booked for them all.”

So what might be done in Ireland to improve the theatre situation?

Dublin’s Lír theatre has been set up as a response to the void of formalised conservatoire training and there have been promising rumblings about the work and training there, according to actress Kathryn McCartin. Colin Teevan thinks Irish theatre could take a leaf from Britain.

“One thing [in Britain] with the Arts Council tightening up, especially on regional theatre, was that you start co-producing,” he says. “I suggested this to the Abbey and they were kind of appalled in their arrogance.

“We did with Dominic Hill (for a show hosted at the Dundee Rep/ Scottish National Theatre in 2007), and again with the Barbican in London. You double your market.”

Back in the West End, Westmeath actress Lisa Dwan is entering her 12th year in London — and more pointedly out of Ireland.

“I think because people tend to know you in Ireland they pigeonhole you,” the 36-year-old replies when asked whether she felt Ireland could match her ambitions. “To this day, I’ve never been invited for an audition in the Abbey Theatre. It’s a closed door; it’s a closed world.

“My work has been supported tremendously in Britain and that’s where all the doors opened up for me. So I stayed here. As a wonderful phrase my grandmother used to say: ‘Bend with the branch that bends with you’.”