IT ALL started in an old honkytonk bar in Nashville, Tennessee. Waterford man Vince Power was in the Southern States for an extended stay. He’d done well in England: his secondhand furniture stores had given him a very comfortable living, so now he was spending time in Tennessee, mainly for the music.

This is the part of America that has given the world the blues, gospel music, jazz and of course country music.

But it is also a grindingly poor US state in some of the rural outposts; this seems likely to have stirred something within Vince Power.

The Kilmacthomas man’s tough upbringing in borderline poverty meant he had empathy for the poor people he encountered in the rural US; it lodged in his mind and would later translate into considerable charity efforts.

Vince was born in Kilmacthomas, Co. Waterford in 1947, one of eleven children (four died in early childhood) — so he knows a thing or two about rural poverty. “My childhood made Angela’s Ashes look like bedtime reading,” he says.

Coming from a rural background, a job in farming seemed an obvious choice, so Vince enrolled at a local agricultural college after school. “I must be the only music promoter with hands on experience of a bull’s sex life.”

But bull insemination as a career path in Waterford had its limitations, so like many before and since, he took the boat to London.

A series of jobs in factories, building sites and shop floors led to Vince working on top of condemned terrace streets. Armed with nothing but a sledgehammer, he would be given instructions to remove a roof, or some similar demolition task; these were projects that would have the health and safety inspectors come down like a ton of bricks on the sub-contractor.

Instead, the ton of bricks almost came down on the young Power. He was knocked from the top of a house that was being bulldozed, the closest to a near death experience he has ever had. He’s had enough.

Vince decided a job opportunity he’d mulled over previously was worth trying. “I thought, why don’t I sell the heavy old furniture that was being left behind. The houses were being demolished, and nobody was picking up the old furniture.”

Accordingly Vince Power took the first step into the world of business.

FLEADH HEADLINER: Vince Power with Shane MacGowan

FLEADH HEADLINER: Vince Power with Shane MacGowan

Hoedown in Harlesden

IN TENNESSEE what struck a chord — almost literally — with the Waterford man was the music of the Southern states. The great traditions of the South were an inspiration to him, not least the country music he was now listening to in this dusty old honkytonk. Why, he wondered to himself, didn’t he open just this sort of place in northwest London. Kilburn, say, or maybe Harlesden . . .

Most people who come up eccentric, not to say far-fetched ideas, usually dismiss it the next morning. But here the philosophy of a fellow Irishman, the Dubliner George Bernard Shaw, seems to have kicked in with Vince: “Some men see things as they are and say why; I dream things that never were and say, why not.”

The Waterford man would probably agree with that, although he might qualify that philosophy. He believes that many ultra-successful people are driven by insecurity. “I don’t especially see myself as a gifted promoter, or a thrusting businessman. But I am willing to take a risk.”

So it was back to London to put that dream into practice,

He ended up with “a grotty old club in Harlesden” bought from a boxer.

Vince loves a wide range of music ranging from the pop music he heard on Radio Luxembourg as a kid to the traditional music of Waterford — his grandfather was a fiddler: in fact the eponymous mean fiddler

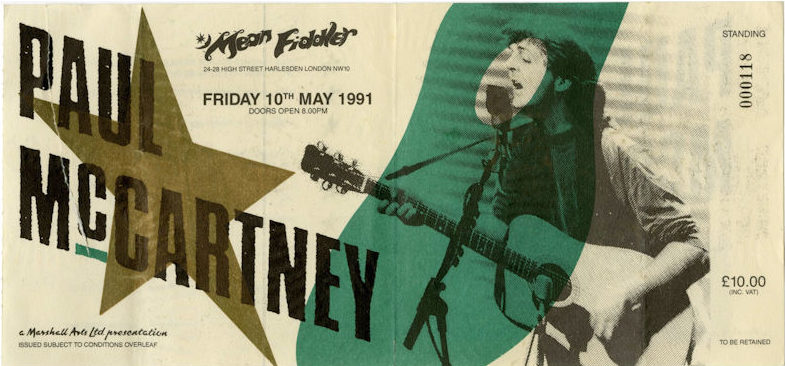

On December 9, 1982 the Mean Fiddler opened in NW10.

“It was my first stab at the music business. I’d been successful in my other business ventures, but after six months it was obvious the Mean Fiddler wasn’t working as a country club.”

Vince decided big names were needed, and again the old Shavian principle of “Why not?” entered into the arena. Vince really couldn’t see any reason that the likes of Roy Orbison, Van Morrison or even Sir Paul McCartney wouldn’t want to play at The Mean Fiddler.

He was right.

Johnny Cash was the first ‘big’ act the Mean Fiddler landed. One of the seminal performers in country music, much of the gravel-voiced Cash's music contained themes of sorrow, moral tribulation, and redemption. He also, somewhat improbably, wrote Forty Shades of Green. So, really, he had something for every Irish person. The Mean Fiddler was on its way.

Tramore trauma

WITH Vince’s eclectic music tastes, the bill of musical fare at the club soon embraced The Pogues, Billy Bragg, The Men They Couldn’t Hang, Kirsty MacColl — as well as many local Irish bands. The legendary Sunday afternoon sessions with Shanty Dam became an institution for Irish London.

Expanding into other music venues was the next obvious move. The Powerhaus in Islington was soon up and running, followed by Subterranea in Ladbroke Grove, The Grand in Clapham, the Jazz Café in Camden and the former Irish dance hall in Kentish Town, The Forum.

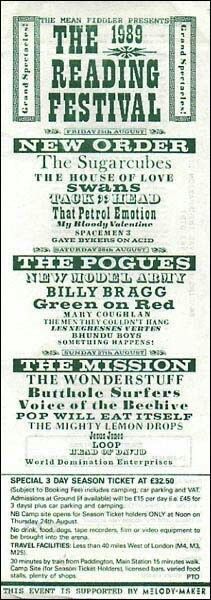

In the late 80s the Mean Fiddler Organisation was responsible for rebooting the Reading Festival, and turning it into one of the premier rock festivals in the world. Other festivals staged by Vince’s outfit soon followed including Phoenix, London Fleadh, Glasgow Fleadh, Madstock and various other Finsbury Park one-off events.

He also played a crucial role in relaunching Glastonbury and helping turn it into not just one of the most sought-after music festivals, but one of the greatest social occasions in Europe.

In 2004 Vince struck a deal with Michael Eavis, the farmer who started the festival off. The festival had been plagued by various problems ranging from gatecrashing to public safety concerns and was in danger of sinking into the Somerset mud. The Mean Fiddler Organisation stepped in, and for a 32 per cent share took care of the logistics and security. The arrangement expired in 2005, but Glasto’s continued success, largely due to Vince Power’s acumen, was secured.

One festival, however, nearly finished Vince Power off. And the irony is that it was in his own home county of Waterford: Fleadh Mór, held in Tramore in 1993, featured musical giants Bob Dylan, Jerry Lee Lewis and Ray Charles, as well as Christy Moore, Nanci Griffith, Moving Hearts, The Pogues and Jimmy Cliff for Saturday’s main stage and Hothouse Flowers, Joan Baez, Jerry Lee Lewis, Shane MacGowan, as well as traditional acts such as The Chieftains.

But the crowds didn’t turn up in sufficient numbers. The vibe was great, but the walk-up didn’t fully materialise.

“I lost a million quid,” says Vince. “It was a brilliant day, but I picked up the bill. I remember on the Aer Lingus plane going home, with lots of revellers and music fans, I was the only one with a sad face.

“The failure nearly broke me. My main thought was, how am I going to get out of this hole? The only thing I could do in the meantime was sell future bookings to Ticketmaster — and that kept me afloat.”

Vintage Vince

RUNNING festivals in Ireland or Britain — indeed anywhere — is a massive risk. The music business itself is a very precarious commercial enterprise, and when you add in factors such as the weather, the vagaries of the fans and the often undulating pulling power of the bands, the treacherous open seas of festival promotion become a gamble that not many people fancy taking on.

In 2004 Vince Power sold his stake in Mean Fiddler plc for £12million.

“I didn’t retire, but there were a lot of other things I wanted to do.”

He’s been as good as his word, continuing to promote fleadhs, acquire new venues, open cafes and bars.

Money doesn’t matter much to Vince. When he sold the Mean Fiddler Group, he had enough to set himself up for life. But that’s really not the Power way. He was soon back in the music business, and it has recently been announced that he’s the owner of the legendary Dingwall’s in Camden Town — although because of contractual factors, he can’t call it that. But undoubtedly the venue is about to return to its former gigging glory.

Vince Power’s own rural poverty is reflected in the number of charitable organisations he’s involved in, particularly Cradle, a Bosnian Children's Charity

Through various fundraising methods, including collections at his festivals, the man who started out life in a grindingly poor family in an equally poverty-stricken country has helped to rebuild a primary school in Mostar, and in Thailand following the Tsunami undertook substantial recovery work. He is also closely associated with the Phillip Hall Memorial Fund. He is a patron of UNICEF and Human Rights Watch.

The Kilmacthomas man should be rightly proud of his life’s work, whether in philanthropy or music promotion, or indeed his in his somewhat brief career as a house demolition ‘expert’. “Charity begins at home” usually means it begins nowhere. It’s a phrase that Vince Power has no time for, and has never used. His charitable acts stretch from Tramore to Thailand, while his business acumen arguably changed the music scene beyond recognition. Festivals, fleadhs, bands and charities have a lot to thank this quietly-spoken Waterford man.