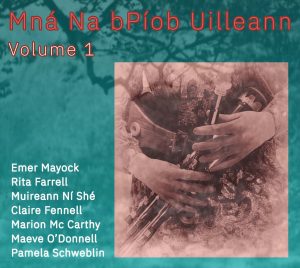

In a groundbreaking shift, the album Mná na bPíob Uilleann: Vol. 1 celebrates the skill and talent of today’s women uilleann pipers, marking a significant change in the instrument's history

The uilleann pipes are technically the most sophisticated member of the bagpipe family. They have a sweeter, mellower tone than the highland bagpipes, and are musically much more flexible — hence their current use in a wide variety of music today ranging from rock to classical.

The name probably comes from the word ‘union’ — the sound being produced through a union of chanter, drones and regulators. There is some speculation, however, that the world ‘uilleann’ is a corruption of the Irish word for elbow.

There are estimated to be as many as 70 distinct types of bagpipe worldwide. The Irish version does have some unique features, the prime one being that the chanter can be closed off, allowing the piper to play discrete notes — in other words, the option to play staccato. The facility to close off the chanter also allows the player to cover two full octaves, something of a novelty in the world of bagpipes.

The uilleann pipes are not a particularly ancient instrument. Their development from the Irish war-pipes of antiquity began in the 18th century – perhaps as an attempt to make the instrument quieter. There were undoubtedly influences from the Scottish and Northumberland small-pipes which are also bellows blown. Some musicologists put the connection stronger than that, citing the these two branches of the bagpipe family as the direct ancestor of uilleann pipes

The instrument was initially favoured by the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, and indeed in the Protestant middle class in general. Church of Ireland vicars would sometimes use a full set in lieu of an organ in church. A uilleann pipes regulators — which allow the player to have a chord accompaniment — has a passing resemblance to the sound of the harmonium.

It was an expensive instrument, which is why it remained in the upper echelons of society for quite a long time, with professional players soon adopting it.

But eventually the instrument was eventually subsumed into the greater Irish music tradition; the pipes became a folk instrument. The instrument became particularly popular in the Travelling community, some of whose exponents help develop the art.

But throughout the uilleann pipe odyssey, no matter which part of society they were played in, the instrument appear to have been the preserve of the male musician — probably more than any other part of Irish traditional music.

Now, in the 21st century, that situation has changed.

Rita Farrell

Rita FarrellThe album Mná na bPíob Uilleann: Vol. 1 is a significant milestone in the history of uilleann piping.

It features seven women uilleann pipers, showcasing their skills and challenging the gender stereotypes associated with the instrument.

It is only probably in the 21st century that a few women uilleann pipers have emerged. Yet in all other spheres — harp playing, singing, dancing and fiddle playing, women are very present, very apparent

It’s not clear why women should have been excluded from piping — directly or indirectly — more so than other instruments used in traditional Irish music but that situation has now changed. The album Mná na bPíob Uilleann: Vol. 1 is testament to that sea change in the history of the instrument.

The album comprises twenty-one selections, with each contributor playing three tracks that demonstrate their individual styles and influences. The geographic spread is impressive — the pipers come across the globe: from Argentina to London, and of course from across Ireland.

Traditional tunes and lesser-known pieces sourced from old music collections make up the repertoire, with some of the ‘big’ piping set-pieces included.

London-born Rita Farrell and Marion McCarthy contribute tracks rooted in the tradition. Marion is daughter of Tommy McCarthy, the Clare-born concertina player and uilleann piper who was a long time resident of north London. Tommy was endlessly patient with young musicians as well as being a maestro on the instrument himself. Marion started playing tin whistle when she was seven and by the time she was ten she performed with her father and brother and sisters at various concert halls in and around London

Waterford’s Claire Fennell contributes tracks rooted in traditional piping repertoire. She demonstrates her ability to play the tight, closed style (think Liam O’Flynn) or the more legato style of Paddy Maloney or Paddy Keenan.

Argentinian piper Pamela Schweblin introduces her pieces from a collection of Irish traditional music published in Buenos Aires. Pamela, a music teacher by profession, was born in Buenos Aires in 1983 and developed a keen interest in Irish traditional music and uilleann piping in her teens through the recordings of The Chieftains and Planxty.

Cork piper Muireann Ní Shé selects slip jigs from the 19th century Goodman collection A native of Dingle, Co. Kerry, James Goodman (1828−1896), was a canon of the Church of Ireland and Professor of Irish at Trinity College Dublin (TCD). During his lifetime he compiled an exceptional music and song manuscript collection which was deposited in TCD Library following his death.

Muireann Ní Shé ahas added her unique interpretation to the tunes.

Maeve O’Donnell, from Co. Tyrone, delivers a powerful rendition of An Bonnán Buí and includes two new compositions, showcasing her expertise in slow airs. Emer Mayock explores the manuscript tradition, drawing exclusively from music sources in her home county of Mayo.

Mná na bPíob Uilleann is the first commercial recording solely focused on unaccompanied women pipers.