MOST people looking for a cultural work that captures a moment in Ireland’s social history will usually find themselves pointed towards the theatrical works of Brian Friel and Sean O’Casey, the poetry of WB Yeats and Patrick Kavanagh or the novels of James Joyce and John McGahern.

But Ireland has also consistently produced some stunning musical works over the past 50 years that have captured the Irish experience: life in small town Ireland; life in “The Smoke”; issues of identity spurned by emigration. Some records, quite simply, captured the spirit of the age. Here are 10 of them.

1. Paradise in the Picturehouse

The Stunning

(1990)

With no short amount of wry humour, The Stunning’s frontman Steve Wall once claimed that his band were “Ennistymon’s answer to The Saw Doctors”, referencing Keith Richard’s claim that The Rolling Stones were “London’s answer to The Beatles”.

The Stunning’s feel good vibes and gang mentality had them pegged, accurately, as an Irish Squeeze: a band brimming with power-pop tunes drenching in sexual imagery. Featuring Brewing Up A Storm, a favourite of almost every pub covers band of the last 20 years in Ireland, the song is about a local lad gone wrong morphing into a Frankenstein — “his eyes are wild / and it can’t go on”.

If anything, though, Paradise… is full of the type of rich, sexual imagery that could only be produced by a band of young men moving out from small-town Ireland and playing gigs “up in the smoke”. Songs such as Romeo’s On Fire and The Girl With The Girl detail a generation pulling away from the sexually tame, church- controlled 1980s and moving towards a more liberal lifestyle.

Equally, one of the band’s best known tunes, Half Past Two shows a band that can convincingly manage the soulful rhythms of Van Morrison while This Happy Girl, the spirit of the entire album, shows the band’s chemistry at its most magical.

2. Same Aul’ Town

The Saw Doctors

(1996)

The Galway band’s best album to date is anchored by the title track; a paean to small town Ireland that almost everyone could recognise instantly — “same oul hanging around the square / same oul spoofers / same oul stares”.

Amid such lyrically strong tunes are a slew of stompers such as World of Good and To Win Just Once, the then unofficial anthem of the 1996 Irish Olympic Boxing team. Perhaps the most striking song, however, is Everyday, a Springsteen-esque tune chronicling the journey of a young girl in “trouble” travelling across the Irish Sea for an abortion.

The song is utterly chilling in its depiction of the woman’s perceived- shame and the clandestine fashion in which she seeks resolution — “She’s the girl you know from down the road / She’s your one from out the other side / There’s a rumour she’s in trouble / She’s all mixed up inside”.

3. Hard Station

3. Hard Station

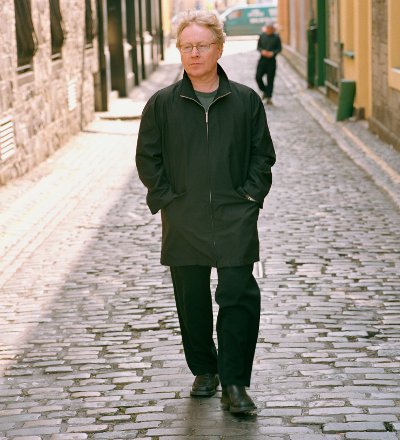

Paul Brady

(1981)

Everybody knows Paul Brady. Without doubt the only Irish songwriter alive with a long, enviable catalogue of original songs spanning four decades, Brady’s first solo record since departing from The Johnsons, Welcome Here Kind Stranger, comprised of covers, the most remarkable being a definitive version of The Lakes of Ponchartrain, which inspired Bob Dylan to revive the song during the 1980s.

Hard Station, Brady’s first album of completely self-penned songs, features many of the same blues, soul and old-school rock ’n’ roll references as The Stunning’s Paradise in the Picturehouse. Most of all, however, it is the sound of a singer- songwriter breaking out of the blocks; songs such as opener Crazy Dreams and Nothing But the Same Old Story, one of the greatest songs about Irish identity ever written, have become set staples for the Tyrone man and, undoubtedly, will be covered by successive generations of Irish songwriters.

4. Heartworm

Whipping Boy

(1995)

As recently as 2013, Whipping Boy’s masterpiece, Heartworm, topped a poll of the best Irish albums of all time, cementing its status as Ireland’s Nevermind. Arriving as it did it in the mid-90s, Heartworm, fittingly, has a foot in both grunge and Britpop: the tsunami of layered guitars, angst and aggression of the former mixed with the direct, instant and focused pop craft of the latter.

Guitarist Paul Page and bassist Myles McDonnell built musical canvases that took the best from The Velvet Underground, Sonic Youth, Spacemen 3 and Echo & The Bunnymen. Vocalist and lyricist Fearghal McKee wrote of an Ireland that seemed uncharted and uncovered, describing the seedy side of life in Dublin.

McKee’s lyrics, though dark and claustrophobic, have an inclusive strand that made fans feels part of a gang: We Don’t Need Nobody Else became a raison d’etre for the band and fans alike, while When We Were Young meant to the Pope’s children what The Undertones’ Teenage Kicks had meant to the generation before.

If Heartworm is the sound of a band in transition, moving into the next dimension, it’s also the sound a generation in transition between the early-90s hangover from the ’80s to the Celtic Tiger years, which really began in 1997, by which time the band imploded and lost steam.

5. Turf

Luka Bloom

(1994)

Having signed to a Reprise / Warner Bros, New York-based Kildare man Luka Bloom (that’s Barry Moore to the taxman) crafted a collection of songs that, although somewhat overproduced, gave a voice to US-based Irish immigrants in the ’80s and ’90s.

Like any number of songs about travelling or emigration, sea imagery features strongly in Bloom’s songs. It’s there in Diamond Mountain — “The cruel sea calls the unwilling traveller/ Who would look for the road to survival” — and in the excellent Sunny Sailor Boy, penned by Waterboys legend Mike Scott, which finds the singer gazing “Over the western sea / startled and struck, / frightened to look / when a mermaid called to me”.

Elsewhere, To Begin To finds Bloom at his wanderlust best, starting out in Prosperous in 1972, Paris, Amsterdam and, finally, California, all in search of songs.

6. Shots

Damien Dempsey

(2005)

Drenched in Irish history and social commentary observed from the northside of Dublin, Dempsey’s third album is infused with the Donaghmede man’s own blend of Irish folk and reggae and is his best record to date. It finds him as a songwriter articulating the conscience of an Ireland very much marooned between its past and its then Celtic Tiger present.

Recorded and released in 2005, songs such as St Patrick’s Day, Colony and Choctaw Nation feature a reading and understanding of Irish history that leaves many of his contemporaries look tame. Similarly, Dempsey’s understanding of where Ireland was at the time, that is, still riding the wave of the Celtic Tiger, is commendable.

Album opener, Sing All Our Cares Away is full of piercing portraits of characters who didn’t benefit from the Celtic Tiger and were blighted by despair, domestic violence and addiction; similarly, Party On describes the ugly aspects of Ireland’s drug culture, which intensified during the notoriously decadent Celtic Tiger years.

A statement of intent, this is Dempsey’s most fully realised collection of songs as he catches the spirit of the age on his own terms, or as he sings in Patience, “From my room in Donaghmede / I’m ’bout to kick all your asses / stick your pink champagne / and f**k your backstage passes”.

7. Planxty

Planxty

(1973)

Referred to as ‘The Black Album’ amongst Planxty fans, you get a sense of just how important Planxty’s music was to a generation of Irish music fans. Featuring the classic Planxty line-up that would reunite for a series of gigs in Vicar Street in 2004, the band’s 1973 debut, according to biographer Leagues O’Toole, “crystallises the 1972 set” of Planxty’s tour.

The band’s remarkable debut opens with Raggle Taggle Gypsy/Tabhair Dom Do Lámh; the former a ballad of a rich lady who leaves her life of luxury for a life to live with itinerants, the latter a tune of joy and, in the context of Raggle Taggle Gypsy, freedom.

Both offer, perhaps, the most appropriate introduction to any band: while the rich lady is joining the itinerants on a journey, you, the listener, are joining Planxty. Arthur McBride, a live favourite at the time of recording and performed heavily by Andy Irvine, Paul Brady and, indeed, Planxty, was a song steeped in the Irish tradition, yet it also chimed well with those singers, songwriters and listeners of folk music who had been energised by the protest songs of the 1960s, particularly those of Bob Dylan, who would later cover the song for 1992’s Good As I Been to You.

The most tender ballad on the album, Ewan McColl’s Sweet Thames Flow Softly feels like a song that Shane McGowan, at the peak of his powers, could have written. Perhaps the only song that dates the album in any way is Kerry-based Fermanagh man Mickey McConnell’s Only Our Rivers Run Free, written as it was to reflect the social and political crisis in the north of Ireland; that song aside, Planxty remains a timeless and unforgettable document of Irish music, refreshing the genre as it did in the ’70s with a prodigious degree of musicianship that is rare.

8. Rum Sodomy & The Lash

The Pogues

(1985)

If Planxty’s natural musicianship and live shows were keeping the flame alive for Irish folk in the ’70s, The Pogues’ fusion of punk and Irish folk energised the genre in the 1980s. Through a series of records that have dated remarkably well when compared to records from the same period, The Pogues’ blend of Irish folk myth with punk and Irish trad was the sound of a band proud to be Irish at a time and place when public expressions of Irish nationality could get you in trouble.

Of all The Pogues’ records, though, it’s their 1985, Elvis Costello-produced second record that finds the band stressing the extremities of their songs, veering from the romantic and sentimental (A Pair of Brown Eyes, I’m Not A Man You Meet Every Day) to the explosive and raucous (Sally MacLennane, Billy’s Bones).

The duality of the Pogues’ sound, which could shift from romantic and elegiac to defiant and up-tempo within two tracks, was, as could only be the case for an Irish band from London, marooned between two different places.

Without doubt one of MacGowan’s finest moments, The Old Main Drag is a picaresque tune of adolescent destitution and addiction that, sadly, wasn’t uncommon — “When I first came to London I was only sixteen / With a fiver in my pocket and my ole dancing bag”. If The Pogues are the undisputed band of the diaspora, then Rum, Sodomy and The Lash is the sound of a band comfortable with that tag.

9. For The Birds

The Frames

(2001)

Half recorded with Nirvana/Pixies producer Steve Albini at his Electrical Audio studios in Chicago, half recorded in a house that the band had decamped to in Ventry, Co. Kerry, Dublin’s The Frames’ 2001 masterpiece For The Birds found the band at a musical crossroads, blending two distinct styles together: the homespun folk of flagship Lay Me Down and the post rock bliss of Santa Maria, named after a shipwreck near where the band were recording.

The Frames’ third album found the band moving away from the Pixies-influenced Dance The Devil… and towards what can only be described a post-rock influenced folk. The entire record finds the singer seeking closure, assurance and progress from, amongst many themes, bereavement, What Happens When The Heart Just Stops and relationships Giving Me Wings.

If For The Birds belongs anywhere, however, it is in every small town and village in Ireland. What hangs over the songs are feelings of restraint and release. In Fighting On The Stairs, Hansard sings “But if I don’t get out of this town now / then something is gonna break / ’cause I gotta find my own way now / through this thick malaise”.

A 10-year anniversary gig in Dublin’s Vicar Street was attended by those who, seemingly, couldn’t release themselves from the grip of this stunning album.

10. The Lion and The Cobra

10. The Lion and The Cobra

Sinead O’Connor

(1987)

Recorded when O’Connor was merely 20 years old, The Lion and The Cobra takes its title from Psalm 91:3, in which God promises protection from danger: “Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.”

That the Psalm is repeated, as Gaelige, with Enya on Never Get Old reinforces the themes of vulnerability and identity that run through the record — “Young man in a quiet place / Got a hawk on his arm / He loves that bird / Never does no harm”, sings O’Connor on Never Get Old.

One of the most auspicious debuts from a solo artist in the last 30 years, The Lion and The Cobra is, in parts, O’Connor at her most raw. On opening track Jackie, vulnerability, identity and loss, again, loom large. It’s a haunting folk tale that, lyrically, is in the vein of Planxty, The Pogues, Paul Brady; in fact, any songwriter who has drunk from the wellspring of Irish folk.

It’s all the more haunting with a ghostly vocal from O’Connor that escalates from a whisper to a scream. Like Dempsey, O’Connor’s lyrics are high on rhetoric and social observations. In A Drink Before the War, restraint and violence and entwined like peace and war, past and present: “You refuse to feel / And you live in a shell / You create your own hell / You live in the past / And talk about war”, which, as they say, “is more Irish than the Irish themselves”.