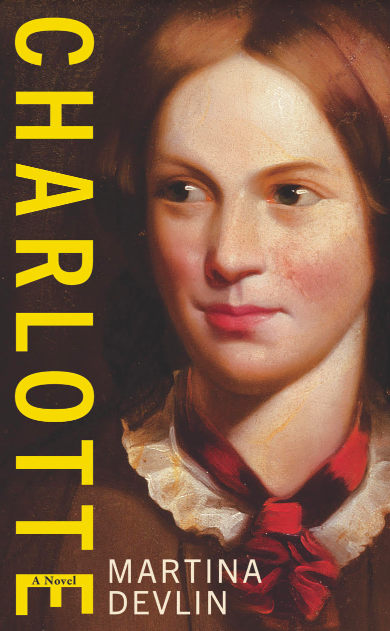

Charlotte: A Novel by MARTINA DEVLIN comes from a deep admiration of the sisters whose legacy lies in their pioneering portrayal of complex, independent women, emotional depth, and Gothic themes in literature

HANDS up, I have a Brontë obsession, and I’m not alone because there’s a term for it: Brontëmania. It manifests itself in minor ways, such as drinking coffee every day from a mug with ‘No coward soul is mine’ (Emily) around its rim and reading by a lamp with a Jane Eyre shade. But I also respect the work: all their novels are lined up on my bookshelves and I reread them regularly,

Long before I thought of writing a Brontë novel, I visited Haworth to walk where the sisters walked and see what their eyes saw.

Years passed, and I made the trip to Yorkshire a second time, on this occasion for research. As I followed the guide about Haworth Parsonage Museum, I was studying furniture placement and views from the windows.

For me, Brontëmania begins with Jane Eyre, Charlotte’s debut novel. Emily’s Wuthering Heights is the most original and Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall the most radical, but in Jane, Charlotte imagined into being one of fiction’s truly memorable female characters.

That unconventional governess is fiercely courageous, outspoken and independent. My views on would-be bigamist Mr Rochester have shifted over the years, and not to his advantage, but my admiration for Jane remains constant.

She insisted on life on her own terms, and told her employer: “I am no bird and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will.”

You may recognise the quote from tote bags and T-shirts, but look for it in the novel – it’s Jane’s expression of self-respect; even for a life of comfort, she will not be caged.

No wonder this work of fiction has made an indelible impression since its first appearance in 1847. “Reader, I married him” – the reader addressed directly – still electrifies today. It’s a sentence shot through power, look at that ‘I’: she chose to marry him. Nothing passive about our Jane.

Jane Eyre the novel is both Gothic classic and feminist rallying cry, and continues to inspire other books, films, television, theatre, musical and dance adaptations. Some are faithful to the facts and some highly fanciful, but all exist because Jane Eyre has taken such an indelible hold on the imagination. One of my favourites is the prequel, Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys, but I enjoy all the Brontë reboots, murder-mysteries included.

Those of us in the Brontëmania camp are as fascinated by the lives of the Brontës as their art. But this involves negotiating a Brontë myth: they are persistently represented as a tragic trio – doomed sisters living in the back of beyond under the yoke of a tyrannical father. However, Haworth was no backwater, and their letters showcase their wit and talent, while Co Down-born Patrick Brontë gave them the run of his library, fostered their education and encouraged them to use their minds and earn their own living.

In seeking publication, the sisters (especially Charlotte) were tenacious and resourceful, despite discouragement and rejection. “Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life,” the poet laureate Robert Southey told Charlotte when she sent him her poems. She ignored his patriarchal putdown and made it her business – as did Emily and Anne.

Charlotte despatched Jane Eyre to the publishing house Smith, Elder & Co in August 1847 and by mid-October her novel was published to instant acclaim. The speed with which it went from handwritten manuscript to printed book still astounds me today. She used the pseudonym Currer Bell because she wanted to “walk invisible” although her identity leaked out.

Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey by Ellis Bell and Acton Bell, aka Emily and Anne, were published two months later. What a year for fiction 1847 proved to be!

But the subsequent year was a traumatic one for Charlotte. While working on her follow-up novel Shirley, her alcoholic and drug-addicted brother Branwell died in September 1848. He was followed by her sister Emily in December, and five months later, in May 1849, Anne also succumbed to TB.

Charlotte could have surrendered to despair, but kept writing. “Take courage,” Anne told her sister on her deathbed, and Charlotte chose her own destiny, setting aside her father’s objections to her marriage and accepting a proposal in 1854. She had a passionate desire for love in her life.

Her husband was Patrick’s curate, Irishman Arthur Bell Nicholls, who took her to Ireland on a month-long honeymoon. They began their holiday in Conwy in Wales, crossed at Holyhead to Dún Laoghaire for several days in Dublin, then onwards to Arthur’s home, Cuba Court in Banagher, Co Offaly. From there, they visited Kilkee in Clare, Kerry and Cork.

In letters back to England she wrote about the Bell family: “I was very much pleased with all I saw, but I was also greatly surprised to find so much English order and repose in the family habits and arrangements. I had heard a great deal about Irish negligence.”

Charlotte died nine months after the marriage, in 1855. Six years later, following his father-in-law’s death, Arthur packed up his mementos of Charlotte and returned to Ireland.

That memorabilia – portraits, samplers, sewing boxes, letters, fairy-sized shoes and tiny-waisted gowns – lay undisturbed in Banagher for decades, even as the Brontë myth put down roots. After Arthur’s death in 1906, a series of auctions took place, and some of the artefacts preserved in Ireland are now on show in Haworth Parsonage Museum.

Objects have power, and those desks and manuscripts, including precocious miniature books written, illustrated and handsewn by the Brontë children, are reminders of three sisters with a genius for storytelling. Women who dared to dream, and worked to make their hopes a reality.

Charlotte: A Novel by Martina Devlin is published by The Lilliput Press

Martina Devlin

Martina DevlinThe Co. Down connection

THE Brontës’ father Patrick Brontë was born and brought up in Co. Down. His family was from Dundalk in Co. Louth and originally called Prunty or Ó Pronntaigh. The son of a mixed (Catholic / Protestant) marriage, he was ridiculed as ‘Papist Brontë’. But both the Presbyterian and Anglican clergymen of the locality realised his great literary talent and helped get him to St. John’s College, Cambridge.

His illustrious offspring all paid tribute to the influence their Co. Down father’s scholarship had on their work.

Here in the heart of rural Ireland Patrick Brontë heard the folklore of his native land. He was a fine writer himself, publishing several poems, but his literary importance lies in the storytelling gift he passed on to his three daughters - tales from his Irish childhood which fed and fired their imaginative genius.

For an expanded Brontë tour, well, nothing beats Banagher. The Co. Offaly town is more generally associated with another writer Anthony Trollope, but Hill House, where the current Church of Ireland canon now lives, was once the home of Arthur Bell Nicholls, Charlotte Brontë’s widower.

Charlotte died, along with her unborn child, on 31 March 1855, at the young age of 38. Her death certificate gives the cause of death as phthisis (tuberculosis), but many biographers suggest she may have died from dehydration and malnourishment, caused by excessive vomiting from severe morning sickness

Patrick Brontë had the melancholy distinction of outliving his wife and all his offspring: Emily, Charlotte Anne, Patrick Branwell, and Maria and Elizabeth who both died as young girls. Towards the end of his life Patrick spoke of returning to the land of his youth in Co. Down, if only for a visit. It wasn't to be, and he died in Yorkshire

in 1861. To journey to either of these areas - the wild Yorkshire Moors, or the rural uplands of Co. Down in the shadow of the Mournes - gives a brief insight into this extraordinary, and sad, literary story.