A man rejects life, takes a job in an asylum and finds the insanity of the patients an appealing alternative to conscious existence. Eighty-seven years later, the novel somehow feels more relevant than ever.

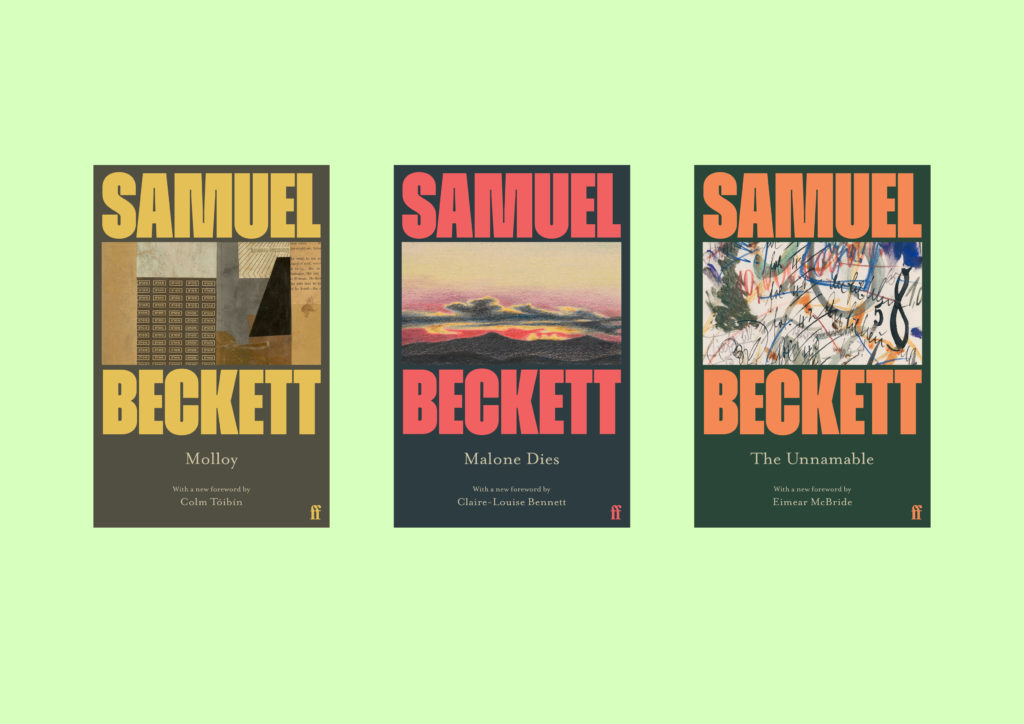

THE PUBLISHER Faber has reissued three of Beckett’s classics this month: Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable. They feature new introductions from Colm Tóibín, Claire-Louise Bennett, and Eimear McBride. The series mark 70 years since Molloy was first published in English.

These books were preceded by Murphy, published in 1938. Beckett’s first published novel* and arguably the most accessible of his major works. A darkly comic, absurdist take on existence, it appears to have been written before Beckett fully committed to bleak minimalism. It is a harbinger, nonetheless, of subsequent books, peopled by lost souls.

Beckett continued to write until his death in France in 1989, but in the end he has these words attributed to him: "Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness."

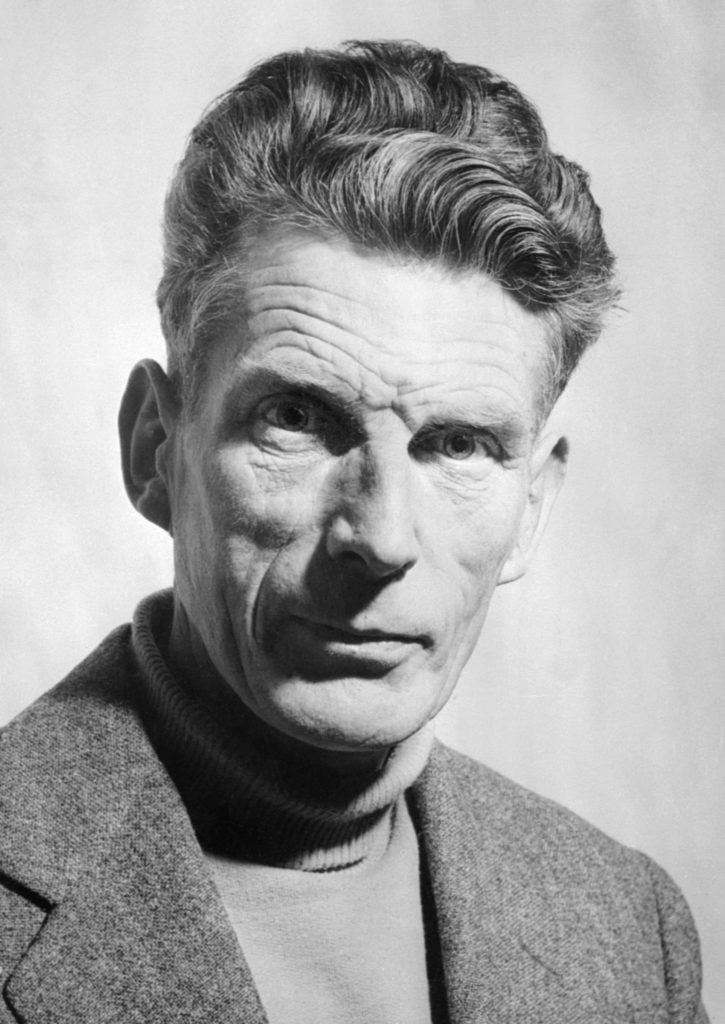

Samuel Beckett in the 1960s in Paris (photo by AFP/AFP via Getty Images)

Samuel Beckett in the 1960s in Paris (photo by AFP/AFP via Getty Images)Plot of Murphy:

Murphy, a workshy, aimless Irishman, rejects both employment and personal responsibility, preferring to sit naked in his rocking chair, contemplating nothingness. In an ill-advised attempt at normality, he moves to London, takes a job in a mental asylum, and discovers that his true home is among the insane. Everything unravels (as tends to happen in Beckett’s writing), leading to a perfec anti-climax.

The book embraces the futility of trying to find meaning in life, the seductive pull of nothingness, and the comedy of human self-destruction.

Vehicle for this enquiry into life’s absurdity:

Murphy himself—a man devoted to doing as little as possible, finding peace only in a catatonic state of inner oblivion. Also featuring: his fed-up lover Celia (who actually wants a life), his eccentric acquaintances, and the mad residents of the Magdalen Mental Mercyseat asylum.

Words never penned by Sam Beckett:

“Murphy learns his lesson.” (He doesn’t.)

Inspiration:

As with all of Beckett’s works, that's a tricky one. The writer’s own life was packed with incident. Living in Paris during the Second World War he joined the Resistance — and was ultimately awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille de la Résistance for his work against France’s occupation.

Prior to that, in 1938 in Paris he was stabbed in the chest and nearly killed when he refused to give money to a small-time pimp whose name was Prudent. His friend James Joyce arranged a private room for him in a hospital. The publicity surrounding the incident attracted the attention of Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, a pianist. They met and a lifelong companionship emerged — Beckett chose as his lover over the heiress Peggy Guggenheim.

At a preliminary hearing of assault against his attacker in a Paris court, Beckett asked his assailant for the motive behind the stabbing. Prudent replied: "I don’t know, sir. I'm sorry.”

Beckett eventually dropped the charges—partly because he found Prudent quite a likeable sort. Could the hapless Prudent have been an early inspiration?

Connection with Murphy’s Law:

The popular phrase “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong” is often linked to an American engineer named Edward Murphy. But given Beckett’s particular brand of cosmic pessimism, Murphy could well have been an early literary embodiment of the idea. Certainly, everything in the novel goes wrong—though Beckett would argue that was the whole point.

A good off-the-wall theory regarding Murphy:

That Murphy’s rocking chair is a metaphor for Beckett’s entire philosophy: movement without progress, motion without direction, a gentle slide toward inevitable doom.

Best line to quote — the opening one:

“The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new.”

From the outset Beckett captures the weary repetition of existence.

Most memorable line:

“Murphy had the illusion not that he was dead, but that he had never been born.”

Which, if you’re feeling upbeat, might not be the best thing to dwell on.

Beckett’s achievement:

With Murphy, he introduces his core themes—absurdity, inertia, and existential paralysis—while still having fun. It’s Beckett before he stripped language to the bone. Later, he would take away plot, punctuation, and even hope, but here he still lets the comedy shine through.

Verdicts:

Some see it as the warm-up to his later masterpieces, others as his most enjoyable work. Murphy is essentially Beckett in a lighter mood—so still dark, but with an occasional chuckle.

Awards picked up by Beckett:

None for Murphy, but later on, a Nobel Prize, which he mostly ignored, and a reputation as one of Ireland’s greatest literary exports—whether he liked it or not.

This article has now done tormenting you with it accursed time (after Godot).

Roger Rees, Matthew Kelly and Ian McKellen in Waiting for Godot at the Sydney Opera House, 2010 (photo by Torsten Blackwood/AFP via Getty Images)

Roger Rees, Matthew Kelly and Ian McKellen in Waiting for Godot at the Sydney Opera House, 2010 (photo by Torsten Blackwood/AFP via Getty Images)*Beckett did write a previous novel Dream of Fair to Middling Women, in English in 1932, when the author was only 26 and living in Paris. However this was not published until 1993, three years after Beckett’s death.