SOMETIMES you write something and without knowing it you tap into a zeitgeist.

More than once I have finished writing, say, a short story, thinking it was original, filled with my own hard-realised truths, only to open a book and be confronted with the experience of a close-to-moment already articulated on the page.

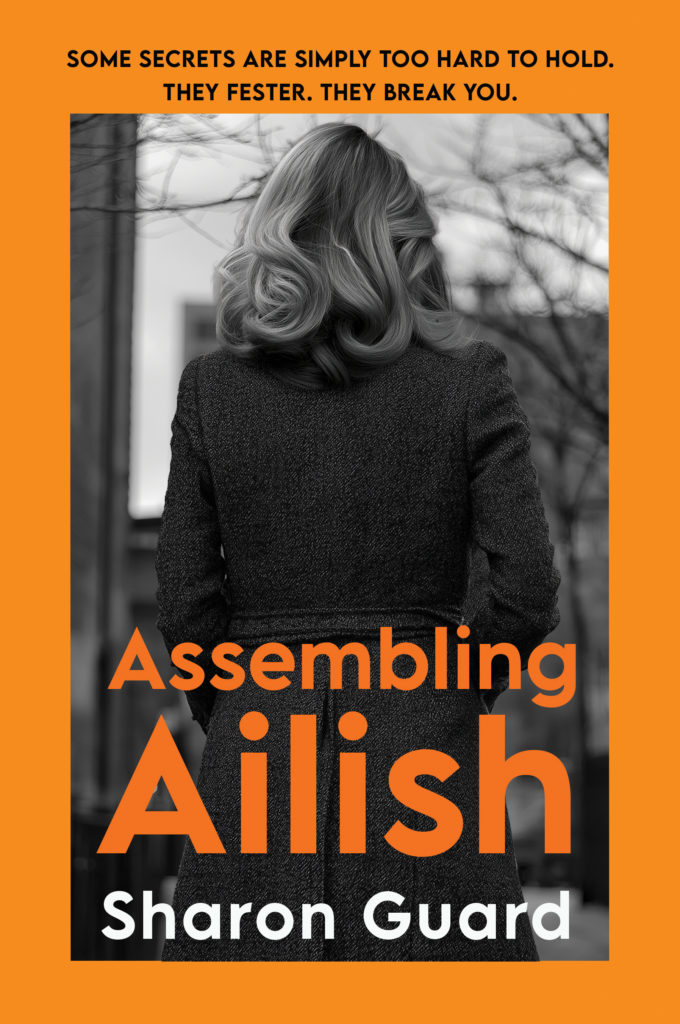

This was the case last year. Amidst the excitement and fear of having my debut novel, Assembling Ailish, accepted for publication, I picked up three newly published books and found parallel stories to the one I had written.

In common with Assembling Ailish, The Amendments, by Niamh Mulvey, Breakdown by Cathy Sweeney, Ordinary Human Failings by Megan Nolan, all feature young protagonists who fall pregnant in the 1980s.

All three stories have different context and outcomes, but all three are stories of lives defined by this event.

As a relic of a 1980s Ireland teenagehood myself, it was clear to me a double blue line on a pregnancy test in those days spelt disaster.

No outcome desirable, regardless of options or choices available.

Assembling Ailish author Sharon Guard (Pic: ConastaPhoto)

Assembling Ailish author Sharon Guard (Pic: ConastaPhoto)What became clearer when researching and writing the book, was how largely oblivious I had been at the time to the wider picture: the societal, institutional and political interests at play in my sexuality. In my fertility.

I went to a convent school. My memories are of an atmosphere where the nuns were reluctantly coming to terms with modernity and change.

Few were left, the older ones relegated to less mainstream subjects such as Latin, and the younger ones strike me now as career women for whom the convent might have been a positive and fulfilling choice.

My mother never worked outside the home after she got married.

A woman who ‘had to work’ was a poor reflection on a husband who couldn’t earn enough to keep her and their children.

Furthermore, her ‘right’ to stay home was enshrined in articles 41.2.1 and 41.2.2 of Bunreacht na hÉireann.

The Marriage Bar on public sector jobs was only lifted in 1973, and the smell of it still tainted the concept of working women.

Many of her generation were trapped by biological and financial imperatives into lives which resembled little more than domestic servitude.

For many, growing up on a diet of American movies and notions of ‘choices’, marriage was still a desirable option. In 1985, when I left school, unemployment was trending around 16%.

When it came down to the hardcore issue of paying for our perms, the narrative of being ‘rescued’ by a Richard Gere lookalike was seductive and immeasurably dangerous to our nascent sexual beings.

I was lucky. The first time I scored a double blue line I was thirty, had already been married three years, and had buried my mother six months previously.

The two events were not unrelated. Motherhood - having one, being one - has always been, for whatever reason – somehow central to my sense of self.

I’m not sure this is a healthy thing. The truth is we will never be tied to another human in the same way we are to the woman who birthed us and it is always a complex proposition, in which at least one party doesn’t have the option of consent.

What struck me most, that first time, was how easy it had been. No complicated moves or scientific interventions, we had decided to be a bit careless and whoa!

There it was. The first faint line was confirmed by a second one and a few of days later a third, stronger one.

This was good news. But. I sat in my office and stared at the wall, the enormity of the undertaking hit in waves.

What if the child wasn’t healthy? What if I couldn’t cope with the basic day to day demands of caring, the tiredness?

What if we couldn’t afford childcare, a buggy, a pram, cot, steriliser, nappies, the university fees?! There is nothing like a double blue line to adult you.

If I felt this way getting pregnant in the best possible circumstances, how would I have felt in the worst? As a teenager, living at home, not finished my education, a whole life ahead changed?

The embodiment of being ‘in trouble’. A pregnancy in the 1980s would have slid me through a veil of thin grey mist to a parallel universe which walked alongside.

Mother and Baby homes were mainstream in this world, and would be for another decade. Nuns were trading children internationally in illegal adoptions, disposing of bodies in sewers, while the bishops struggled to suffocate a growing tide of victims finding the courage to speak of sexual abuse.

If I felt a disquiet in the nuns, it was because they knew they were sitting on a volcano.

None of this was clear when the country was asked to vote in the abortion referendum of 1983. Soundbites – as they often do – won out, and the country couldn’t bring itself to vote to harm a living being.

The justification for ignoring the rights of women: they have sinned. Shame and blame were the tools we - and our mothers - were given to manage our fertility, in lieu of that other rather more nuanced and suspicious duo: health and care.

The fact of fertility makes us goddesses and it makes us she-devils. We have the power to gift life. To not gift it. And church and state systems – regardless of location or culture or era - always have complex self-interests to ensure our desire to do this is controlled.

Assembling Ailish is published by Poolbeg Press

Assembling Ailish is published by Poolbeg PressMargaret Attwood famously claims her 1985 novel The Handmaids Tale was inspired by actual history and happenings. A not-so-dystopian vision of a patriarchy manipulating individual lives to ensure its own form of survival.

In 1980s Ireland, as we danced with abandon to Like A Virgin, access to contraception was difficult, required a prescription. The sale of condoms was only fully decriminalised in 1993.

Between 4,000 and 5,000 women – more likely young girls – made the impossibly difficult decision every year to ‘get the boat’ to England for an abortion. My character Ailish, was one of these.

Her mother, God-fearing Barbara with a history of her own fertility problems, arranged it.

If you sit with a group of women of a certain age anywhere in Ireland today, they know, or ‘know of’ somebody who was in this position.

The other stories – the babies who were born in mother-and-baby homes or the like and given for adoption, show up as adults.

The brave women, and their families, who kept their babies, and dealt with the consequences of that. Hopefully mostly joyful, but difficult nonetheless.

If Assembling Ailish is part of a fictional trend, it is maybe that these stories have simply found their time to be told. With the benefit of distance, they can be put into context.

These characters – mine, and those others who currently grace the shelves of our bookshops –can speak for real-life contemporaries in a way that people engage with, through story.

For those who cannot tell their stories. Who have maybe never told their stories.

Assembling Ailish by Sharon Guard is published by Poolbeg Press