Alannah Hopkin (image by Nelius Buckley)

Alannah Hopkin (image by Nelius Buckley)Mary Kenny reviews Alannah Hopkin's biography Patrick-from Patron Saint to Modern Influencer

My local supermarket in Kent has been heralding St Patrick’s Day since mid-February — with large cardboard harps marking out the shelf for Guinness. Similarly, the stationery shop has been displaying greetings cards for March 17, featuring leprechauns dancing a jig.

Harmless harbingers of the Irish national holiday – which is now internationally observed. But amongst all the paddywhackery, has the man himself, the first Patrick, been forgotten or eclipsed? It sometimes seems like that.

Yet, as Alannah Hopkin stresses in a new edition of her beautiful and accessible biography of Patrick -– the saint really does play a significant role in the formation of Irish culture.

It was after Patrick’s evangelisation of Ireland (432AD is a broadly accepted date) that what we now call “early Christian Ireland” emerged. The awesome era of Irish monasticism, which Lord Clark claimed saved Christianity in Europe, really flowed from this event. “Irish history begins with Patrick,” Alannah Hopkin states.

Patrick also penned the first Irish autobiography, his famous Confession, and his writings are still studied as meaningful historical sources. His “sincerity, humility and steadfastness” are evident.

The basic outlines of his story were once known to every schoolchild. He grew up somewhere along the west coast of Roman Britain, the son of a well-to-do family. Then, at 16, he was captured by Irish slave raiders – the Irish of the time were notorious slave-traders – and brought to a remote part of Ireland to work as a shepherd, and a swineherd.

He writes of his loneliness and isolation: but in this time of trial he found his spiritual awakening. Freed after six years, he subsequently returned to Ireland to bring Christianity to the pagan Irish, competing with the druids for miracles and messages.

Ireland gave him a warm welcome at his second coming. Conversion was “unparalleled for its lack of bloodshed” - it took an entirely peaceful course. The Irish were ready and receptive - another biographer, Roy Flechner of Trinity College Dublin, has suggested that Irish noblewomen were Patrick’s first followers, bestowing their jewels on him to sustain his developing mission.

Patrick wasn’t the sole source of Ireland’s Christianity: the faith had been “infiltrating” Irish clan society, via Gaulish missionaries, since the 4th century. Bishop Palladius, a deacon of the Roman church who preceded Patrick, had had earlier success. But it was Patrick who, somehow, sealed the deal and became the symbol of Irish faith and national identity over the centuries, to the point where every Irishman was sometimes known as “Paddy”.

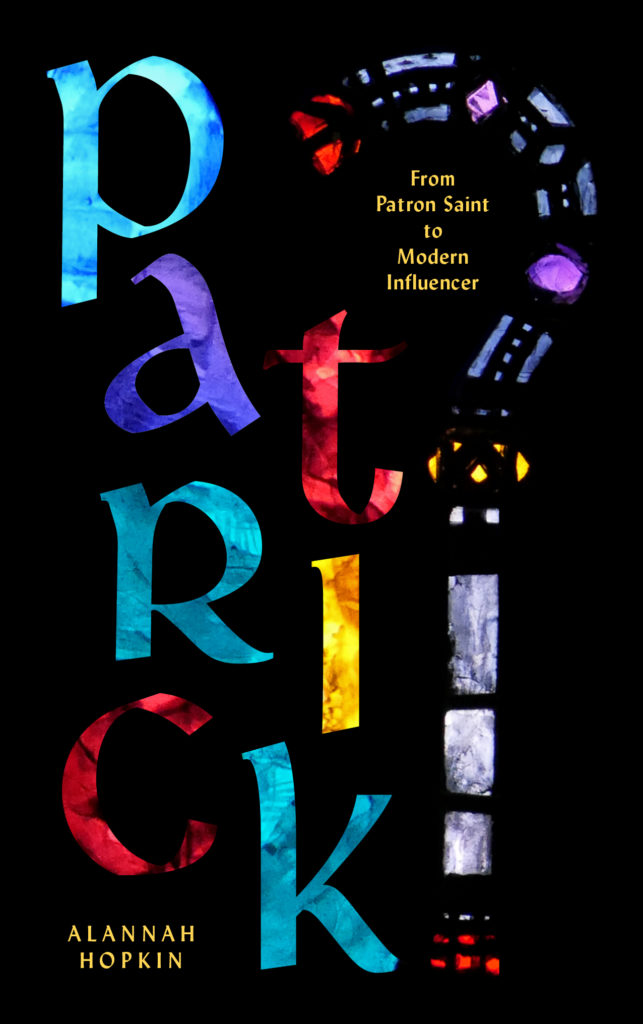

The author illuminates her book with stunning pictures of stained-glass windows depicting Patrick, from such fine artists as Harry Clarke, Evie Hone and Patrick Pollen. St Brendan’s church windows in Loughrea are especially impressive.

Alannah Hopkin lives in West Cork – she is the daughter of an Irish mother and an English father; she is also the widow, and biographer, of the literary novelist Aidan Higgins. Travelling around Ireland, she provides a geographical guide to those locations associated with Patrick: the inspiring Croagh Patrick in Mayo, still a place of modern pilgrimage, the austere but compelling St Patrick’s Purgatory at Lough Derg, the tomb of the saint at Downpatrick – which may not really be his burial place, but is still a hub of Patrician interest.

And the Church of Ireland, too, has been dedicated to Patrick over the centuries – sometimes claiming he was really more like an Irish Protestant than an Irish Catholic in his practices. He was, indeed, very knowledgeable about the Bible and lived by the Scriptures.

Patrick became more identified with growing Irish expressions of nationalism from the sufferings of the Penal Times, and emigrants to America truly put the shamrock on the map. (Though we don’t know if Patrick ever actually used the shamrock as the symbol of the Holy Trinity, as reputed.)

Legends arose – such as the story that he banished snakes from Ireland, but we may take that more as metaphor than fact. The Romans were aware that Ireland had no snakes. Yet myths and legends aren’t always wrong, and often derive from folkloric history.

Ireland is a more secular – and multi-cultural – society today so perhaps it’s understandable that a Christian saint seems less relevant to younger people. But Patrick bestowed on Ireland a unique “brand” – from the famous monastic settlements to the shamrock on the tail of an Aer Lingus aircraft – and he surely deserves to be centre stage for his feast-day.

It’s reckoned that over half a million Brits have taken up Irish passports since Brexit – through a parent or grandparent – and I’ve encountered some who admit to knowing little about Ireland. A readable, beautifully-illustrated book about St Patrick is their chance to start exploring their cultural roots! ENDS.

Patrick – from Patron Saint to Modern Influencer by Alannah Hopkin. Published by New Island books. £21.99 in the UK.

Mary Kenny is an internationally renowned author, journalist and broadcaster. She has a special interest in the relationship between England and Ireland.

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny