THROUGHOUT the England football team’s journey to the final of Euro 2020 this summer, the phrase ‘gesture politics’ gained prominence.

It was the expression used by the Home Secretary, Priti Patel, in directing fire at the England players for their decision to ‘take the knee’ in solidarity with victims of racism.

What struck me as wrong was not only her refusal to condemn those who chose to boo this gesture, but her derogatory inference that such gestures can only ever be shallow.

Following England’s defeat to Italy in the final, we witnessed again why the cause of anti-racism is so important, and through the statements of many of England’s players we saw a group whose commitment to that cause is anything but shallow.

When gestures come from a place that is authentic and born of experience, rather than being dismissed as ‘gesture politics’, they can carry powerful political significance.

When Nelson Mandela shook the hand of South Africa’s Francois Pienaar at the 1995 Rugby World Cup Final, before presenting him with the trophy, it was not dismissed as gesture politics.

When Pope Francis knelt to kiss the feet of rival South Sudan leaders and pleaded with them not to return to civil war, it was not dismissed as gesture politics.

And when Sinn Féin’s Martin McGuinness, shook hands with Queen Elizabeth in 2012, it was not dismissed as gesture politics.

In a speech in Westminster a few years later, Martin described the handshake as being “in a very pointed, deliberate and symbolic way offering the hand of friendship to unionists through the person of Queen Elizabeth, for whom many unionists have a deep affinity".

Far from being a shallow gesture, it was an act of political leadership from a man who sought to move the Northern Ireland peace process and British-Irish relations further forwards, reciprocated by a woman who understood things in very much the same sense.

A handshake, especially one which takes place between people who are perceived to be adversaries, can be the most powerful political gesture of all, synonymous with both the sealing of a deal and as a universal symbol of peace.

I’m not sure what gesture would symbolise this Tory government’s approach to Northern Ireland and British-Irish relations, but it would not be a handshake or any symbolism involving more than one actor.

Because their approach is to act only in their own interests.

Where the previous two Tory governments were often characterised by ignorance, this one is defined by its cynicism.

They have decided to act unilaterally in reneging on promises and against agreements they themselves have made and which go against their duty as the British government to protect the letter and integrity of the Good Friday Agreement itself.

The Labour Party in Britain must, and is already, presenting a clear public opposition to the actions of the Tory government.

That is something which carries great importance for the Irish community in Britain.

On the proposals to introduce an amnesty on prosecutions for alleged crimes committed during the Troubles, the Tories calculation is that in Britain they will be met by apathy, at worst, and a sense that this happened a long time ago in a land far away.

That sense of disconnection and distance is not the case and I say that as a relative of Father Hugh Mullan, a Catholic priest killed unlawfully by a British soldier in the Ballymurphy Massacre in 1971.

The more people you speak to in the Irish community in Britain, the more connections you’ll find to victims of the Troubles who are living here today.

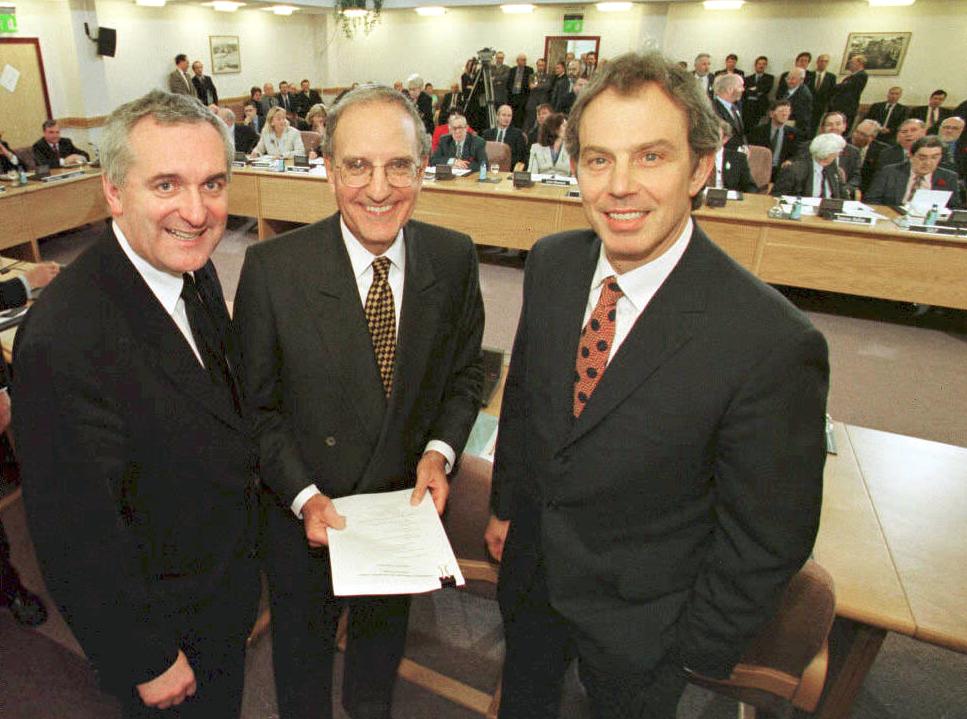

Then Prime Minister Tony Blair (R), US Senator George Mitchell (C) and Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern (L) smiling on April 10, 1998, after they signed the Good Friday Agreement

Then Prime Minister Tony Blair (R), US Senator George Mitchell (C) and Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern (L) smiling on April 10, 1998, after they signed the Good Friday AgreementAnd as Michael O’Hare, a prominent member of London’s Irish community, told me last week ‘the passage of time makes things more difficult, not less’ in seeking justice for his sister Majella who was killed unlawfully by a British soldier in South Armagh in 1976.

Trust and agreements matter, and the Labour Party will always be the party of the Good Friday Agreement in Britain for two important reasons.

First, the values of that agreement and the Labour movement are shared values – solidarity, equal rights and cooperation.

Second, Labour has an historic relationship with the Irish community in Britain.

It does not simply engage or listen to the Irish community but is greatly enhanced by its Irish voices elected to public office at every level across Britain.

I know there was some concern recently at comments made by Labour’s leader Keir Starmer in response to a question on Ireland’s constitutional future posed by the BBC’s Enda McClafferty.

I was pleased to see unequivocal public clarification of Labour’s long-standing and only position that it is for the people of Ireland, north and south, to determine their own future.

In the months ahead, whether it be in opposition to an amnesty or support for the terms agreed in the NI Protocol, the Labour Party and the Irish community in Britain will be working together hand in hand.

That is not gesture politics, but one built on a deep relationship established over many decades.

Liam Conlon is Chair of the Labour Party Irish Society